This content originally appeared on MadeByMike and was authored by Mike

I went to a JavaScript meet-up in Sydney the other night and asked the question "How many people know what CSS Architecture is?". The room was full of different people with varying backgrounds and experience. I thought at minimum around a quarter might know what I was talking about. I was hoping more would. To my surprise, only a handful of people raised their hand.

I then asked, "How many people feel the difficulties they have writing CSS at scale have been largely solved by CSS-in-JS?". They weren't stupid, they knew this question was a set-up, nonetheless, many of them obliged me and put their hand up.

From the looks in the room, I think many more people felt this way than were willing to admit. At the very least, I think a lot of people believe CSS architecture is no longer relevant in the context of modern JavaScript applications.

That perspective was very kindly put to me by Alex Louden on Twitter:

"Styled Components etc has removed the need for class names completely for me. Now since styles are included in my presentation components (to me at least) it doesn’t feel like a style architecture issue any more?"

This is not to criticise that perspective; it's completely valid! Alex is saying tooling helped make some of the challenges he had dealing with CSS (in particular specificity) easier. The challenge now is dealing with components in an application.

I understand this perspective, but find it interesting when people see classnames and components as completely different concerns. Classnames and components are just different ways of composing user interfaces. There are still many challenges involved in making good re-useable and scalable front-end systems, no matter how you put them together.

These challenges are not new. In fact, there are some well established solutions in CSS architecture that can be easily transferred to component-based style systems. So why are so few people talking about this? And why are many more people completely unaware of the topic?

I believe there is a lot that has contributed to this and it's worth reflecting on how we got here...

How we got here

I believe the initial response to CSS-in-JS, from many leaders in the CSS community hasn't helped with understanding and knowledge sharing. I've often heard comments like "People (i.e. younger JavaScript developers) just need to learn CSS better." People who have knowledge about CSS architecture need to do a better job of articulating this experience in a way that is accessible and relevant to new developers. If I'm honest about it, the CSS community has failed at this.

But it's not that simple. There are some non-human factors and context we need to consider as well.

Before the rise of JavaScript components. The strong and obvious naming conventions of BEM gave developers a system to follow that helped avoid specificity clashes in the "terrifying global scope" of CSS. This alone was reason enough for many people to use BEM. You could get good enough results, without necessarily understanding nuanced reasons behind the conventions.

When JavaScript tooling provided a better solution than humans following naming conventions, it opened up UI development to a wider spectrum of developers who previously had less interest in, or reason to focus on, style architecture.

Business jumped on the dogpile. They reasoned it would be cheaper to employ developers who could "do everything" and got what they considered to be adequate results by under-investing in UI specialists. Some developers who'd spent half a career perfecting skills in this area felt threatened. Perhaps some were defensive.

At the same time, developers working in spaces of growth and opportunity could sometimes be dismissive of skills that were not flavour of the month. There was pride, and hype, and reluctance to admit that new tooling and approaches were not always producing better, more re-useable, front-end architecture.

I've been consulting in this space for the last 5 years and I've seen many different systems for building UIs with component-based architecture. The reality is, whilst some aspects of building large scale JavaScript applications are easier, the promise of better, more re-usable UI components hasn't been delivered. Front-end architecture is more varied in approach and the results less re-useable than it was before the rise of JavaScript tooling.

Some people might challenge this, but I've seen enough examples to consider it an objective truth. What I have seen is:

- almost every team has a different approach,

- 90% of components get zero re-use,

- visual changes are often difficult, slow and expensive,

- it's harder than ever to read and understand styles.

Somewhere in the turbulence, we lost the more nuanced reasons behind the naming conventions.

The aim of this was to give context, not blame (it's a little bit of everybody's fault). So let's draw a line, and look at how to apply some lessons from CSS architecture to modern JavaScript applications.

CSS Architecture for Components

First of all, we need to consider what makes sensible abstractions in UI development. OOCSS, SMACSS and BEM all have a common language when they talk about the different parts of a UI component. I can summarise these as:

- Layout,

- Design,

- UI states, and

- Application logic

If re-use or long-term maintainability is important, keeping these concerns separate is beneficial. Yet, this is not typically how teams approach the design of a component library.

Components can do many things, they might fetch data, they might render HTML, they might call functions to execute business logic and manage application state. Sometimes a single component does all these things. There is usually little distinction around what the responsibility of a component should be. People draw boxes around the visual boundaries of a design and then mix this with application logic. That's how most components are built. We can do better than that.

BEM gave semantic meaning to classnames and one of the biggest unseen values in this was we could immediately transfer our intentions to other developers across teams and even projects. If you know BEM you can look at a classname, e.g. button--state-success and immediately recognise this as a modifier for a button class.

This kind of semantic meaning is sorely needed for components.

With that in mind, let's look at different parts of a UI component, identified in CSS architecture methodologies and redefine them in terms of component architecture.

Layout components

Find a way to distinguish layout components in your application. It might be a comment in the file, a naming convention or the organisation of components in folders... it doesn't matter. What matters is we need a way to convey our intentions quickly to other developers.

When we have common understanding of what a layout component is we can enforce expectations in code-reviews or linting.

Layout components:

- own responsibility for layout and nothing more

- should never apply any presentational styles

- should not contain any application logic

- own responsibility for the layout of child items.

That last point might be a little confusing at first. Why children and not themselves?

In modern CSS there are two parts that contribute to layout:

- A parent item, which sets the display mode

- A child item, which participates in the parent items display mode.

In other words, we have a grid-container and grid-items, or a flex-container and flex-items. There is always a parent/child relationship.

To get the intended layout, we need the parent item and the child item to work together. Updating one of them independently from the other, will result in a broken layout. We have a word for this, it's called a dependency.

Despite this dependency, we continue to make these separate components with no direct link. We simply hope that people put them together in the right way and don't change them. We call that an unmanaged dependency.

The solution is to co-locate the layout concerns with the parent item. There are a number of ways this can happen...

Use A * Selector

Use the cascade to your advantage and apply a * selector to target all immediate children of a layout component.

For example:

.layout {

display: flex;

}

.layout > * {

flex-basis: 50%;

}This works, even with CSS-in-JS and you might be interested to know the * selector doesn’t increase specificity, so it’s easy to override with classic CSS, should you need.

This might seem simple, but it works in most cases.

Render mark-up that wraps child items

Another option is to make the layout component responsible for rendering mark-up that wraps child items.

This allows us to more directly control both sides of the parent/child relationship and is useful for ensuring semantic and accessible mark-up.

const Layout = ({items}) -> (

<ul classname={parentStyles}>

{items.map(item => (

<li classname={childItem}>{item}</li>

))}

</ul>

)In the example above I'm ensuring the children of a ul will always be an li. At the same time I'm applying styles for the layout to both the parent and child items. These are managed somewhere in the layout component.

Export styles to be used by child-items

The biggest downside of rendering mark-up that wraps child items is you need to pass a list of items that get rendered into specific slots. That's ok for a simple list, but not ideal for more complicated layouts. As a final escape hatch for complicated components, you can export styles from the parent to be used by a child item.

This allows us to co-locate layout concerns for a particular component.

import { sectionHeader } from "./Page";

const Heading = () => <h1 classname={sectionHeader}>A Heading</h1>;In the example above Heading still needs to be a child of Page but the dependency between these components is no longer hidden.

By passing just the layout styles between components (not presentation) we're being explicit about what the dependency is. The Heading component is still responsible for any presentational styles applied to the h1.

Presentational components

Once again we need a way to convey intentions and set expectations about what aspects of UI development presentational components are responsible for. It should be immediately apparent that a component is a presentational component.

Presentational components:

- deal with visual design,

- contain no application logic,

- set no

displayor positioning properties, - are (mostly) just decorated HTML elements,

- should be size agnostic.

Once again, the last point is the least intuitive. Size agnostic means presentational components should fill the space available. Trust in the layout components to set the constraints.

In practical terms this means most UI components have no display, width, height or margin properties.

This is sometimes hard to achieve. Working on presentational components is going to reveal problems or oversights in the layout (or even missing layout components). It feels easier to quickly add a margin to 'fix' the presentational component, but by keeping the responsibility for layout with the parent item, presentational components can be re-used in any part of the application.

By adding CSS to presentational components to 'fix' layout issues, we are adding hidden dependencies between components. For long term maintainability, it's far better to fix these problems at the layout level.

I know this is not always simple, so I'm going to give you an escape hatch. However, consider this the !important of CSS-in-JS. Use it when you absolutely must, and use it right. For certain types of components (usually inline-block elements where content is dependent on dynamic data and there is no obvious parent layout component) it sometimes makes sense to add a utility class, or a prop to set a single CSS property. If possible, these should still remain separate from the presentational component and be imported from a utility file. I suggest naming this liabilities.js or debt.js.

Always try to avoid hard coding width and height in presentational components.

UI states

Both layout and presentational components have different types of UI state. UI state is different from application state, but the two are often conflated in modern web applications.

From a UI development perspective, the state of a component refers to different display or layout variations that might occur when a user interacts with it.

As a UI developer knowing the number variations and what styles are applied in each case is not only critical, it's the job description. So why has this has become so hard to know in modern JavaScript applications?

When props are passed to a function that resolves styles, the number of variations can be hard or impossible to verify. This is an example from a real-word application I worked on:

import { theme } from "theme.js";

const styles = ({ selectedItems, activeItems, id }) => {

return {

backgroundColor: selectedItems.includes(id)

? activeItems.includes(id)

? theme.color

: theme.colorAlt

: activeItems.includes(id)

? theme.color

: null,

":hover": {

border: `solid 1px ${theme.colorAlt}`

}

};

};These styles are so difficult to reason about because you have to consider how the application state (props) effects each individual CSS property.

Not only does this make it hard to read, it makes it difficult to test. If the props passed to a style function don’t represent a finite set of UI states, how do we know the current set of resolved values is something intended in the design?

Once again CSS architecture taught us some things about how to manage UI state. SMACSS in particular talked about state and identified three different types of UI state:

- Modifier states

- Behavioural states

- Pseudo states

I'm paraphrasing, because SMACSS was not thinking about components, so let's revise some of these ideas for modern front-end architecture.

Modifier states

Modifier states are top-level variations in design. They are not necessarily dependent on application state and may be applied as a stylistic choice.

Examples include size variations, primary and secondary buttons, or the position of an image within a layout component.

Modifier states can be extended with behavioural states.

Behavioural states

Behavioural states are dependent on application logic. They communicate something about the state of a component to the user. Examples might include success, failure and loading indicators, or the current item in a navigation menu.

Pseudo states

Pseudo states are more temporary. They usually map directly to persistent states in the browser, rather than application logic. Typical examples include hover, focus and active but this might also include disabled or selected.

UI states are finite

The solution to verifying UI states is to resolve styles down to a set of finite states that can be easily understood.

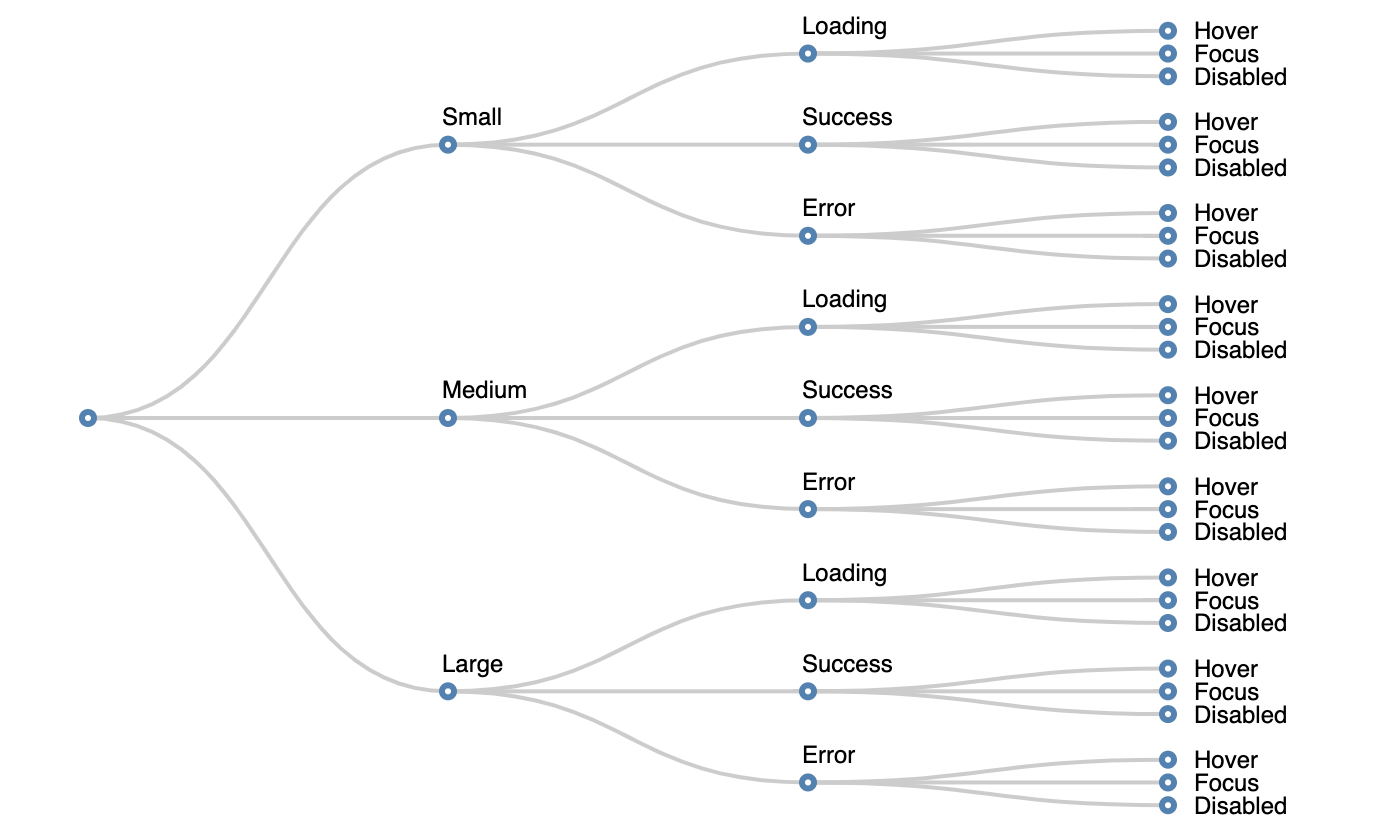

To ensure this, I start by mapping out UI states into a table:

| Modifier state | Behavioural state | Pseudo state |

|---|---|---|

| Large | Loading | Hover |

| Medium | Success | Focus |

| Small | Error | Disabled |

Next consider how these states combine. Typically you only have one modifier and one behavioural state active at any one time.

You can visualise this as a tree:

If you find it's possible to have two behavioural states active at the same time, split them into different categories.

| Modifier state | Network state | Todo state | Pseudo state |

|---|---|---|---|

| Large | Loading | To Do | Hover |

| Medium | Success | Doing | Focus |

| Small | Error | Done | Disabled |

Warning: If you find you do need this, consider carefully, as it’s often a sign that you have two components pretending to be one.

Because state can be additive, (i.e. behavioural states can change depending on the modifier state), to work out the total number of variations, we multiply the possibilities. With 3 types of state and 3 possibilities for each, there are (3 x 3 x 3), 27 possible variations.

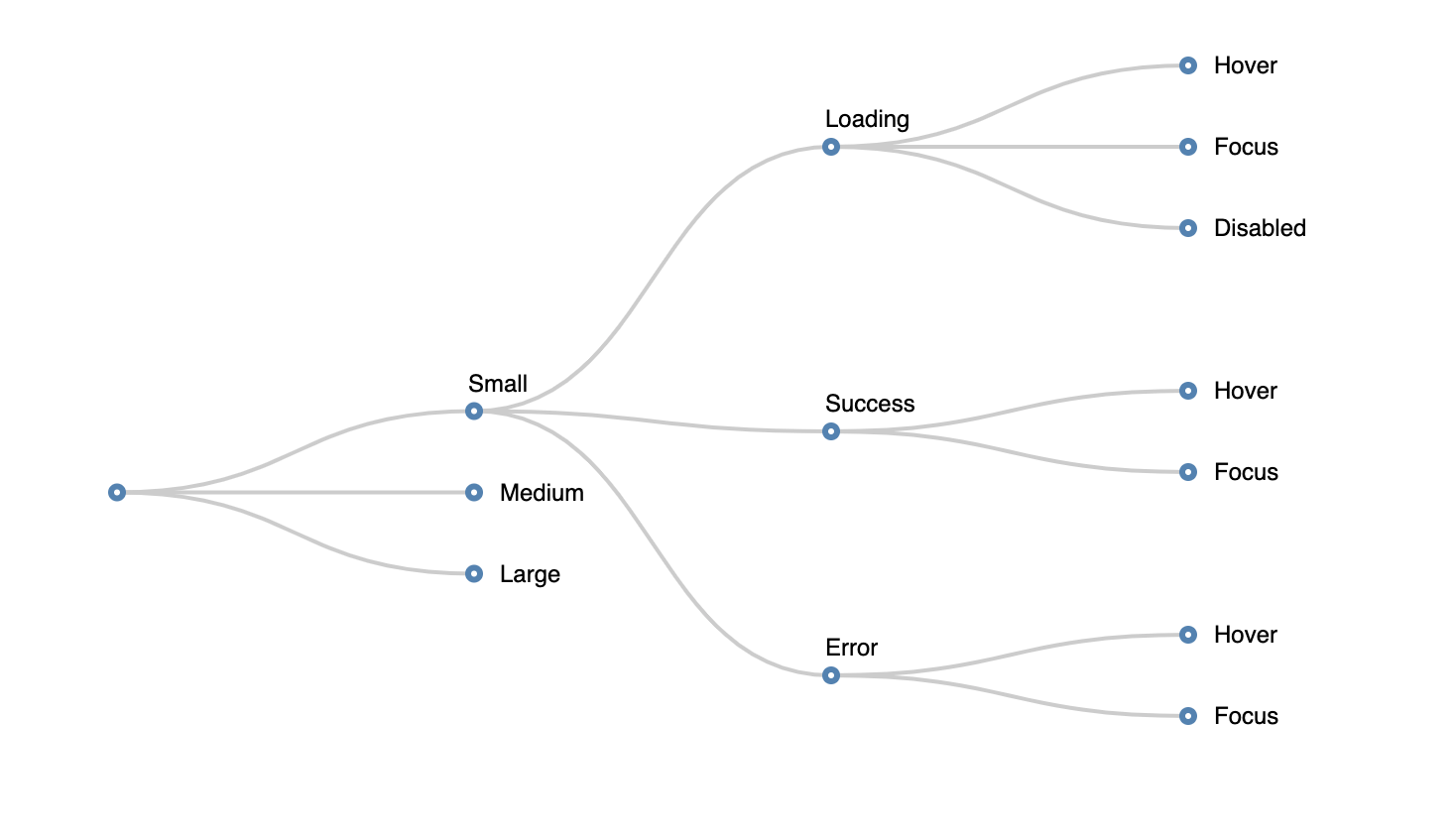

Obviously not every combination matters. The disabled state might look the same for every type of modifier and maybe the pseudo states are the same for all modifiers. We can eliminate duplicate states:

CSS forced us to flatten the state tree and have a single selector for each possible combination of state. Although sometimes tedious, this made us acutely aware of how many variations there were.

JavaScript doesn't force us to flatten the state tree in any way. The concept of different types of UI state often lost and at worst the value of individual CSS properties depends on the resolution of business logic and data within the “style sheet”.

It doesn’t matter whether you’re composing styles with classnames, template strings or objects in JavaScript. It remains important to have a single representation for each of the possible UI states.

My current favoured approach is to resolve application logic outside the style function, then and pass keys for modifier and behavioural state. Where a behavioural state changes depending on the modifier, I use CSS custom properties to set variations that are later applied in the behaviour.

const modifiers = {

light: {

color: "#777",

"--pressed-color": "#333"

}

};

const behaviours = {

pressed: {

color: "var(--pressed-color, #777)"

}

};

export const style = ({ modifier, behaviour }) => ({

fontSize: "1em", // Default Styles

...modifiers[modifier], // Apply Modifiers

...behaviours[behaviour] // Apply Behaviours

});This allows me to have additive states with a fairly flat and readable representation of each of the styles applied to each variation of a UI component.

Container components

The final type of component we need to distinguish is a container component. Many people might already have an understanding of what this means, but from a UI perspective, I'm not referring to any particular design pattern.

From a UI perspective a container component is simply where the application logic is resolved down to a set of modifiers and behavioural keys that are passed to presentational and layout components.

A container component:

- contains no presentation or layout styles

- should not render mark-up (except children)

- can wrap layout and presentational components

- may fetch data, setup events, refs etc...

- is where non-reusable code lives.

But it's only UI!

As the responsibilities of front-end developers have become more broad, some might consider the conventions outlined here to be not worth following. I've seen teams spend weeks planning the right combination of framework, build tools, workflows and patterns only to give zero consideration to the way they architect UI components. It's often considered the last step in the process and not worthy of the same level of consideration.

It's important! I've seen well-planned project fail or go well over budget because the UI architecture was poorly planned and became un-maintainable as the project grew.

This disappoints me because the problems are hard and my colleagues and friends who helped establish best practices in CSS are serious engineers, with broad skills, who applied knowledge across disciplines.

Many of the ideas in CSS architecture predate CSS itself and have strong foundations in computer science and software architecture. I know developers who can understand complex architectural problems but fail to see the similarities, or worse yet, choose not to apply this knowledge to declarative front-end code.

I know you can do it. To help, I've got some questions to ask yourself when planning UI components.

Questions to ask when planning UI components

- How many UI states does this component have?

- Can I easily validate the current UI state?

- How ergonomic are my styles? (i.e. how quickly can someone else read them)

- Am I creating sensible UI abstractions? Or am I drawing boxes around the visual design?

- Am I separating layout form visual design where possible?

- Am I separating application logic from UI components?

- Am I communicating my intentions to other developers and giving semantic meaning to components.

Keep practising this and you will build better lasting UIs.

This content originally appeared on MadeByMike and was authored by Mike

Mike | Sciencx (2019-11-23T00:00:00+00:00) CSS Architecture for Modern JavaScript Applications. Retrieved from https://www.scien.cx/2019/11/23/css-architecture-for-modern-javascript-applications/

Please log in to upload a file.

There are no updates yet.

Click the Upload button above to add an update.