This content originally appeared on CSS Wizardry and was authored by CSS Wizardry

One of the key tools that performance engineers have at their disposal is the Performance Budget: it helps us—or, more importantly, our clients—ensure that any performance-focused work is monitored and maintained after we’ve gone.

By establishing an acceptable threshold, be that based on RUM data, bundle analysis, image weight, milestone timings, or any other suitable metric, we can be sure that new or unrelated bodies of work do not have a detrimental impact on the performance of our site.

The difficulty, however, lies in actually defining those thresholds. This post

is for anyone who has struggled with the question, But what should our

budgets actually be?!

Targets vs. Safeguards

When faced with the task of setting a brand new budget, it can feel daunting—almost paralysing—trying to find a value that is both attainable but effective. Is it too ambitious? Is it not ambitious enough? Is it going to be really difficult to hit? Or do we risk making it so easy to achieve that it’s almost pointless? How do we know? How long will it take to find out?

Here’s the thing: most organisations aren’t ready for challenges, they’re in need of safety nets. Performance budgets should not be things to work toward, they should be things that stop us slipping past a certain point. They shouldn’t be aspirational, they should be preventative.

Time and again I hear clients discussing their performance budgets in terms of

goals: We’re aiming toward a budget of 250KB uncompressed JavaScript

;

we hope to be interactive in 2.75s

. While it’s absolutely vital that

these goals exist and are actively worked toward, this is not part of your

budgeting. Your budgeting is actually far, far simpler:

Our budget for [metric] is never-worse-than-it-is-right-now.

The Last Two Weeks

Whatever monitoring you use (I adore SpeedCurve and Treo), my suggestion for setting a budget for any trackable metric is to take the worst data point in the past two weeks and use that as your limit. Load times were 7.2s? You’re not allowed to get any slower than that. JS size was 478KB? You can’t introduce any more without refactoring what’s already there. 68 third party requests? You can’t add any more.

Then, every two weeks, you revisit your monitoring and one of three things can happen:

- Your new worst-point is better than the last one: This is the best outcome! Let’s say you went from a 7.2s load time and now your worst value is 6.8s—well done! Now your budget gets updated to 6.8s and your job is to not regress beyond that.

- Your new worst-point is the same as the last one: This is still good news—we haven’t regressed! But we haven’t improved, either. In this scenario, we don’t need to do anything. Instead, we just leave the budget as it was and hope we can continue on the same path.

- Your new worst-point is worse than the last one: Uh oh. This is bad news. Things have slipped. In this scenario, we do not alter the budget. We can’t increase budgets unless there is a very valid and agreed reason to do so. Instead, we double down on solving the problem and getting back on track.

By constantly revisiting and redefining budgets in two-weekly snapshots, we’re able to make slow, steady, and incremental improvements. But the key thing to remember is that we can’t ever increase a performance budget; we can’t change the test just to make it passable. We can maintain or decrease one, but we can’t increase it, because that would completely undermine them.

Example Performance Budgets

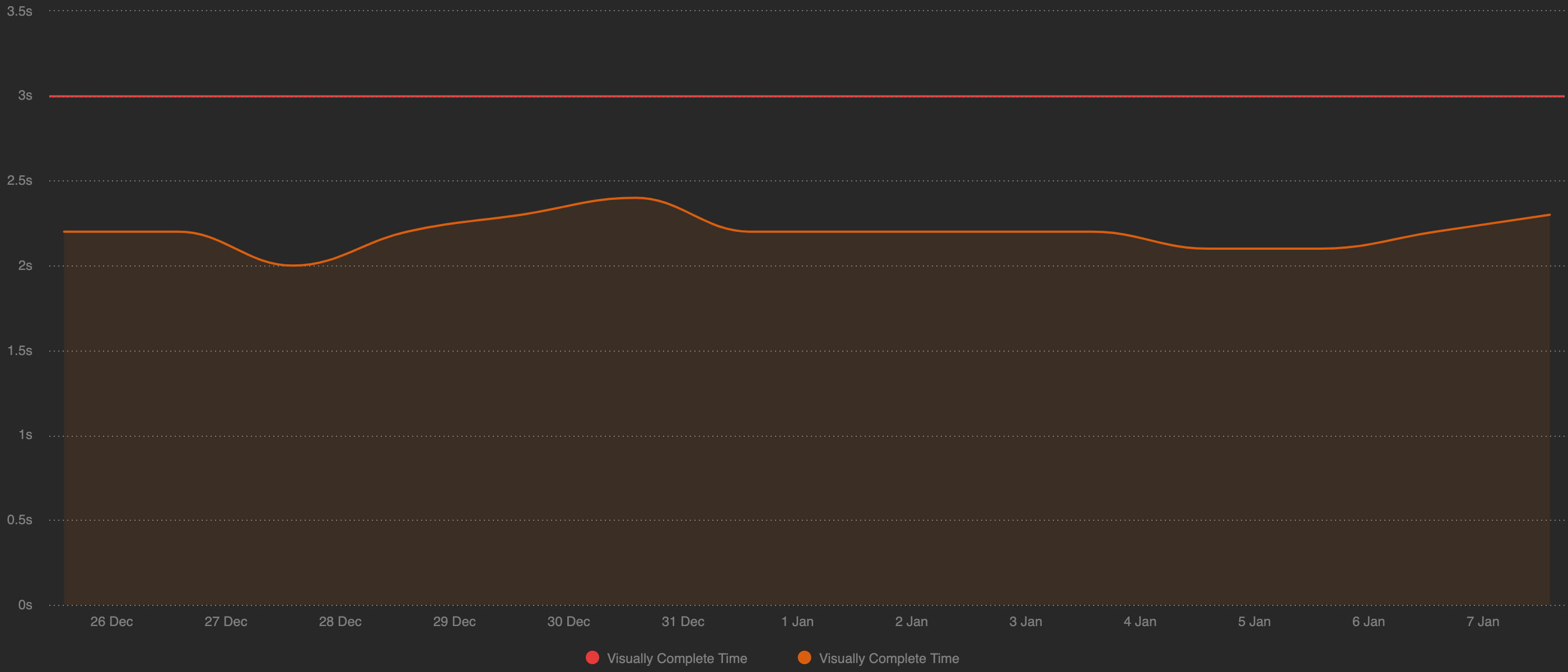

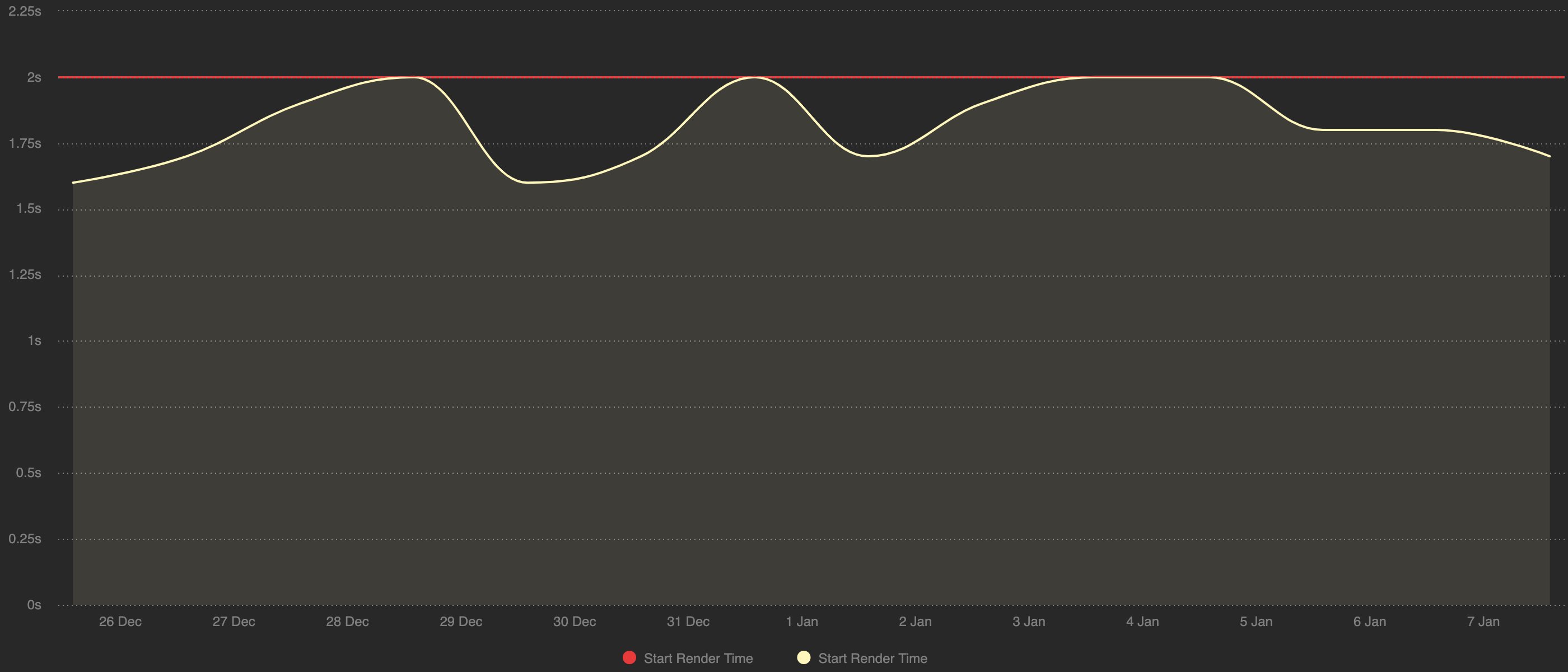

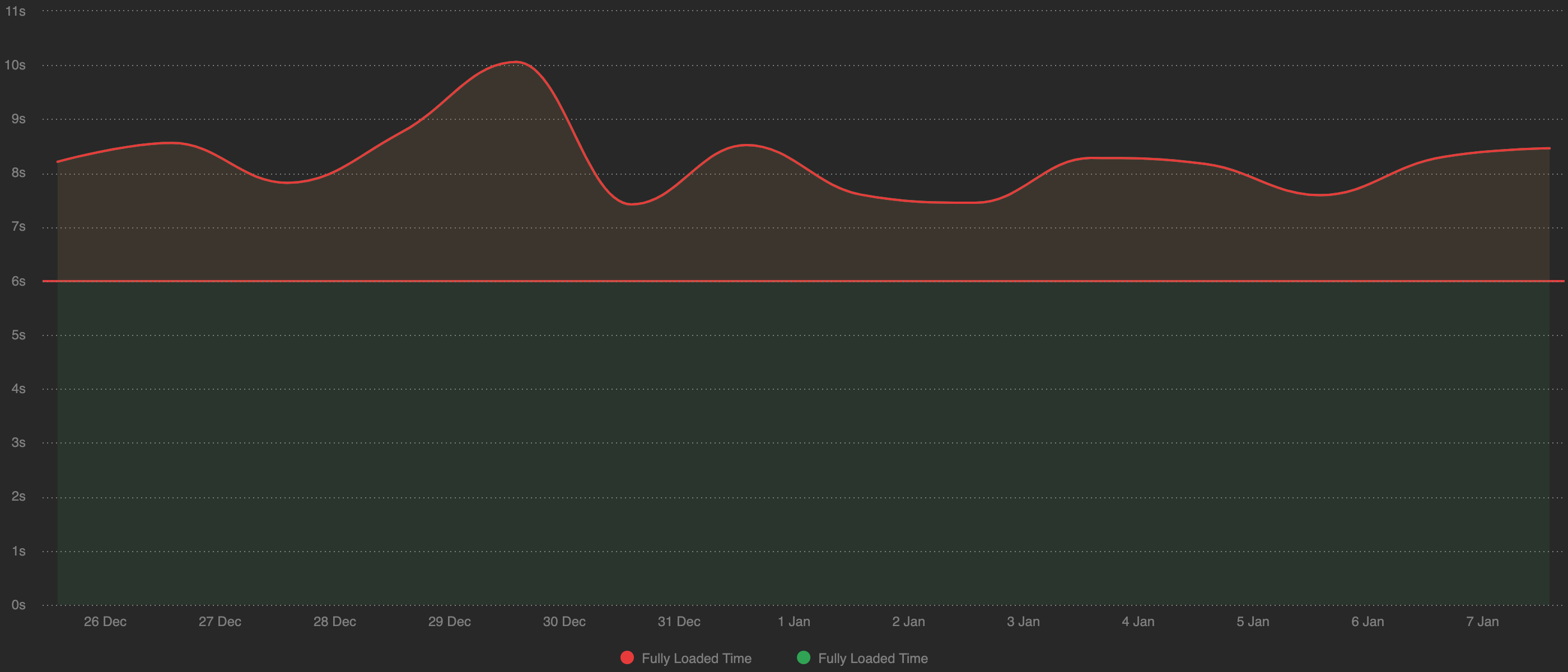

The following SpeedCurve charts respectively show the Visually Complete, Start Render, and Fully Loaded budgets for CSS Wizardry over a 3G Galaxy S4 from the UK.

Under Budget

I’ve set a Visually Complete budget of 3s, but I’m doing far better than that every single day across the last fortnight. The slowest Start Render in that period was 2.4s, so I need to update my budget accordingly and maintain the new maximum for the next two weeks before revisiting once more.

On Budget

With an allotted budget of 2s for Start Render, I find that on most days I am actually quite nicely under budget, which is great news. That said, on four occasions I am just nudging the line. This means that I need to be mindful over the next two weeks, but do not need to update anything. This budget is probably quite sensibly set as it’s clearly attainable, but is on the verge of needing some proactive input to keep within the bounds.

Over Budget

Uh oh. I’m completely overshooting my Fully Loaded time every single day, and sometimes by up to four seconds. I can’t reset the budget (unless it’s decided that for some reason 6s was completely incorrect in the first place) but I do have some work to do. Clearly I have decided that load times are important enough to be monitored, so I need to roll up my sleeves and get to work fixing things.

Your Turn

Setting performance budgets doesn’t need to be complex or confusing, you simply need some existing data, some monitoring, and to remember that budgets and targets are two different things. Don’t make life difficult by treating performance budgets as aspirations.

This content originally appeared on CSS Wizardry and was authored by CSS Wizardry

CSS Wizardry | Sciencx (2020-01-08T18:19:10+00:00) Performance Budgets, Pragmatically. Retrieved from https://www.scien.cx/2020/01/08/performance-budgets-pragmatically/

Please log in to upload a file.

There are no updates yet.

Click the Upload button above to add an update.