This content originally appeared on Web development blog - Manuel Matuzović and was authored by Manuel Matuzović

According to WebAims annual accessibility analysis, 98.1% of home pages of the top 1,000,000 websites have detectable WCAG 2.0 failures. Some of these sites may only have minor contrast issues or maybe just a single missing id, while others are highly inaccessible. However, this number is pretty damn high, considering the fact that automatic testing tools only report obvious accessibility issues.

Only 1.9% of the tested home pages pass automatic testing, which is fine, but it doesn’t mean that there aren’t any barriers on these websites either. True accessibility extends beyond automated tests and WCAG regulations.

It's fair to say that most websites are only accessible to some.

98.1% sounds bad, but for most of us it’s just a number, isn’t it? For me, as someone whose job it is to help others build accessible websites, it’s easier to imagine what the real-life effects of these failures can be. To help you get a better understanding of what this high percentage means for users and their daily experiences on the web, I created a little experiment.

My partner is an architect, and she sparked my interest in modern architecture. That’s why I built a web page about an architectural movement in Europe, and for my experiment I would like you to open the page and read it. Once you’re finished, try to summarise what you’ve just learned, rate your experience and then please come back to the article.

Impressive stuff, right? I hope that you could access most of the information without using DevTools. I did everything I can to make it as accessible as possible. If you had trouble understanding what the page was about, please note that:

- Our developers (me) spent countless hours optimising the accessibility and we’re proud that Lighthouse, Wave, and Axe don’t throw any errors.

It’s 100% accessible. - It’s your choice how you access the page, but it’s optimised for desktop screen readers. You will have the best experience if you don’t use a mouse. You can download NVDA for free.

- This is an early version of the web page and we’re exploring ways to make these types of pages accessible to everyone.

- Unfortunately, we don’t have the budget to optimise it for non-screen reader users. The money is not worth spending on this niche market.

- Why would people using a mouse want to access a website about expressionist architecture anyway!?

- We focus on our target audience, VoiceOver on macOS, NVDA, and JAWS users, but we’re also evaluating accessibility widgets that we might add to the website for others. This improvement will allow you to click around as much as you want and optimise the website to your needs.

This will make the website 120% accessible. - We’re known for top-of-the-line websites and we’re constantly exploring new technology. We’re considering using AI to draw images based on the information in the

altattribute.

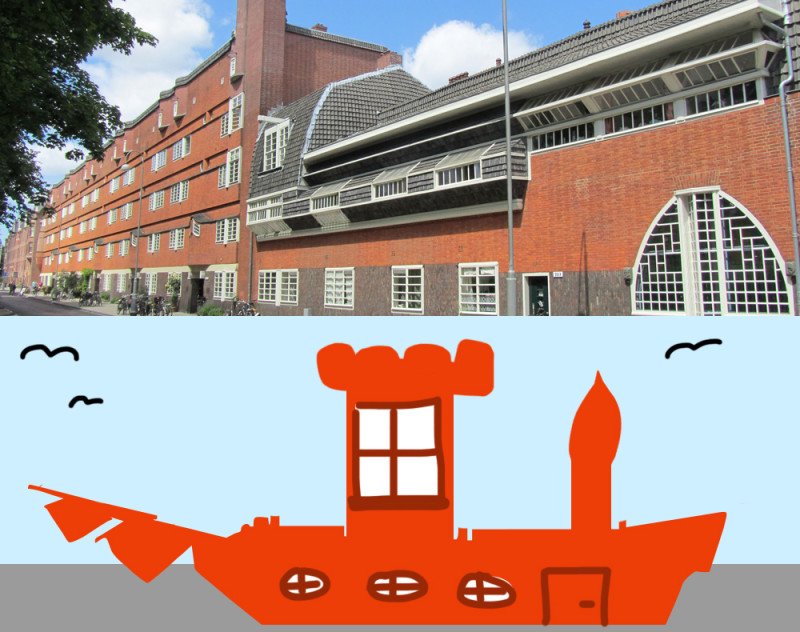

Based on thealttext “A long rectangular building. Besides looking like a ship, Het Schip resembles a bizarre art form. Its appearance is unconventional from all angles. The exterior consists of bright orange bricks, decked with towers and architectural elements in unconventional shapes.” our AI super algorithms created the following image:

We are getting there.

I guess that most of you could not access all the information. How does that feel? Especially with my bullshit justifications. Pretty bad, right? Now imagine having a similar experience on most websites you visit. That’s not just annoying and troublesome, but it makes you angry and sad.

Please remember how this experience made you feel every time you work on a new website, page, or component. Make your websites accessible to all, not just to some.

Behind the scenes

You probably want to know how I built this exclusive website. Please be aware that most of the following code samples (I’ve marked those that aren’t bad) illustrate poor and dangerous practices. I wrote them just to make a point, don’t use this code on real websites.

Labels

It’s hard to understand what a page is about, if there’s no h1 or if it isn’t labelled properly.

<h1 aria-label="Expressionist architecture">Document title</h1>“Document title” is shown, but a screen reader announces “Expressionist architecture”.

Note: aria-label must not be used that way. You don’t need it, if there’s text content already.

Further reading

Control hints

Screen readers provide users with instructions on how to interact with elements like links. Additional hints like “click this link to..” or “press this button” are superfluous.

<a href="https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Expressionism">

expressionist

<span aria-hidden="true">(Click your mouse to open this link)</span>

</a>Some links in my experiment show an additional “(Click your mouse to open this link)” instruction next to the link text.

Further reading

Different language

The lang attribute is important. Applied to the html element, it tells screen readers the natural language of the page. A screen reader might not detect the language automatically; the lang attribute helps it pick the right voice profile.

If you switch language within a sentence, you can use the lang attribute to mark a word or phrase. (That’s a good practice.)

<p>There's a certain <span lang="fr">je ne sais quoi</span> in the air.</p>If you don’t do that, it might cause an English voice profile pronouncing a German sentence with an English accent. This can be hard to understand and confusing, just like switching language mid-paragraph.

<p class="u-vh">

Expressionist architecture is one of the three dominant styles of Modern…

</p>

<p aria-hidden="true">

Expressionismus in einer der drei dominanten Stile der modernen Architektur…

</p>One sentence is in German, but it’s hidden from screen readers.

Further reading

Image

A missing alt attribute is bad, but an alt with wrong or useless information isn’t much better. Please don't annoy your screen reader users with long, boring, or irrelevant information.

The alt attribute is often misused as a place to store SEO keywords or copyright information. Here I turned it around and put all the useless information in the image.

<figure>

<img

src="hetschip.jpg"

alt="A long rectangular building. Besides looking like a ship, Het Schip resembles a bizarre art form. Its appearance is unconventional from all angles. The exterior consists of bright orange bricks, decked with towers and architectural elements in unconventional shapes."

/>

<figcaption>

Dutch expressionism (Amsterdam School), Het Schip apartment building in

Amsterdam, 1917–20 (Michel de Klerk)

</figcaption>

</figure>Further reading

Empty Link

It’s common for screen reader users to encounter empty links and buttons. Their screen reader might tell them they’re on a link, but if there’s no text, they don’t know where it will take them.

By using aria-label I made the label accessible to screen readers only.

<a href="https://" class="btn" aria-label="Het Schip on wikipedia"></a>aria-label is often used to provide labels for icons. I’m not a fan of conveying information with icons only because the lack of text my increase cognitive load by requiring mental processing to infer meaning.

Further reading

Wrong order

Screen readers announce content in the order they appear in the DOM, top to bottom. Changing the order in CSS has no effect on the order in the document. It’s hard to navigate and understand relations between elements if they appear in an incomprehensible order.

<p aria-hidden="true">

Brick Expressionism is a this movement special variant of The Netherlands and

northern Germany in western and in.

</p>

<p class="u-vh">

Brick Expressionism is a special variant of this movement in western and

northern Germany and in The Netherlands.

</p>Further reading

Hidden content

Developers came up with a nice workaround for situations when it's just too hard to make parts of a page accessible, they simply add aria-hidden="true" to an element and hide it from screen readers. If it doesn't exist, it doesn't have to be accessible. ? *

<p style="filter: invert(1);">The term “Expressionist architecture…</p>Note: I tried using color: #FFFFFF; and opacity: 0; to hide the text visually but axe is too smart. I was able to trick that tool by using filter: invert(1).

* That was sarcasm. You know, just in case…

Further reading

Click here

Screen readers can do much more than just announce content in a page, they provide different ways of navigation. You can jump from landmark to landmark or heading to heading, or you can list all form items or links on a page. If these elements don’t have a meaningful label, it’s hard, or sometimes even impossible, to tell what their purpose is, just like a paragraph where every link has the same label.

<p>

Important events in Expressionist architecture include the

<a

href="/wiki/Werkbund_Exhibition_(1914)"

aria-label="Werkbund Exhibition (1914)"

>

click here

</a>

in…

</p>Further reading

Excessive nesting

The structure of a page should be clear and simple. No one benefits from 8 nested articles or uls.

<ul aria-hidden="true">

<li>

The style was

<ul>

<li>

characterised by an

<ul>

<li>

early-modernist adoption

<ul>

<li>

of novel materials,

<ul>

<li>

formal innovation,

<ul>

<li>

and very unusual

<ul>

<li>

massing

<ul>

<li>.</li>

</ul>

</li>

</ul>

</li>

</ul>

</li>

</ul>

</li>

</ul>

</li>

</ul>

</li>

</ul>

</li>

</ul>Further reading

Forms

Creating accessible and usable forms is hard, but there are a few basics that we just have to get right.

- Every form item needs a label

- Labels should consist of text and not just of images or icons

- Labels and form items should be grouped in a way that both machines and users understand their relation.

I made the proper label “bad” only accessible to screen reader users by hiding it visually and I disabled clicking by adding pointer-events: none; to the label.

<p>

<input type="radio" id="rating2" name="rating" />

<label for="rating2" style="pointer-events: none">

<span class="vh">bad</span>

<span aria-hidden="true">Circled white star Circled white star</span>

</label>

</p>There’s more than that. I can recommend Form Design Patterns by Adam Silver, if you want to learn how to make inclusive forms.

“Buttons”

A common accessibility issue is the presence of elements on a page that look like buttons, but aren’t actually <button>s. This usually makes them less accessible or inaccessible to some users. Here I turned it around: It’s a real button, it looks like a button, but you can’t click it.

<button

style="pointer-events: none"

type="submit"

class="btn"

onclick='alert("Thank you for your rating");'

>

Send

</button>Further watching

Conclusion

That was a fun experiment and I hope that you had joy reading this article. The underlying issue, though, is no fun at all. That’s just my way of dealing with serious topics.

Your website, app, or new feature is only half as good if only some people can access it. Consider inclusion and diversity from the very beginning and test properly. A score of 100 in Lighthouse or 0 errors in axe doesn’t mean that you’re done, it means that you’re ready to start manual testing and testing with real users, if possible. Before just you build and launch something, think about your users first and how your decisions might affect them.

Here’s the accessible version of the page about expressionist architecture.

Thank you, Carie Fisher, for helping me with this article!

This content originally appeared on Web development blog - Manuel Matuzović and was authored by Manuel Matuzović

Manuel Matuzović | Sciencx (2020-06-24T06:58:54+00:00) Accessible to some. Retrieved from https://www.scien.cx/2020/06/24/accessible-to-some/

Please log in to upload a file.

There are no updates yet.

Click the Upload button above to add an update.