This content originally appeared on Modern CSS Solutions for Old CSS Problems and was authored by Stephanie Eckles

Accessibility is a critical skill for developers doing work at any point in the stack. For front-end tasks, modern CSS provides capabilities we can leverage to make layouts more accessibly inclusive for users of all abilities across any device.

This post will cover a range of topics:

- Focus Visibility

- Focus vs. Source Order

- Desktop Zoom and Reflow

- Sizing Interactive Targets

- Respecting Color and Contrast Settings

- Accessibility Learning Resources

What Does "Accessible" Mean?#

Accessible websites are ones that are created without barriers for users of various abilities to access content or perform actions. An internationally agreed-upon standard called the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines - or WCAG - provides success criteria to help guide you towards creating accessible experiences.

Common accessibility barriers include:

- inability to see content or distinguish interface elements due to poor color contrast

- reduced or removed access to non-text content such as within images or charts due to failing to provide alternative text

- trapping keyboard users due to not managing focus for interactive elements

- causing headaches or worse for users with vestibular disorders due to motion and flashing/blinking animations

- preventing users of assistive technology such as screen readers from performing actions due to failure to make custom controls accommodate expected patterns

- limiting common assistive technology navigation methods due to not using semantic HTML, including heading hierarchy and landmark elements

Success criteria "are designed to be broadly applicable to current and future web technologies, including dynamic applications, mobile, digital television, etc." We are going to examine a few success criteria and how modern CSS helps provide accessible solutions.

Focus Visibility#

An all too common violation that I have done myself in the past is to remove :focus outlines on links, buttons, and other interactive controls. Without providing an alternative :focus style, this is immediately a violation of the WCAG Success Criterion 2.4.11: Focus Appearance.

Frequently, the reason this is removed is due to feeling the native browser style is not attractive or doesn't fit in with the design choices of the site. But with modern CSS, we have a new property that can help make outlines more appealing.

Using outline-offset, we can provide a positive value to position the outline away from the element. For the offset, we'll use the em unit to position the outline relative to the element based on its font-size.

Bonus: We're setting the

outline-widthvalue using themax()function to ensure it doesn't shrink below a computed value of1pxwhile allowing it to also be relatively sized usingem.

Select the demo button to display the :focus outline.

CSS for "Focus Styles With Positive `outline-offset`"

button:focus {

outline: max(1px, 0.1em) solid currentColor;

outline-offset: 0.25em;

}

Alternatively, set outline-offset using a negative value to inset the outline from the element's perimeter.

CSS for "Focus Styles With Negative `outline-offset`"

button:focus {

outline: max(1px, 0.1em) dashed currentColor;

outline-offset: -0.25em;

}

There is also a new pseudo-class that you can consider using in some circumstances. The :focus-visible pseudo-class will display an outline (or user-defined style) only when the device/browser (user agent) determines it needs to be visible. Typically this means it will appear for keyboard users upon tab key interaction but not for mouse users.

Using this update, our button styles will likely only show when you keyboard tab into the button.

CSS for "Focus Styles With Negative `outline-offset`"

button:focus {

outline: none;

}

button:focus-visible {

outline: max(1px, 0.1em) dashed currentColor;

outline-offset: -0.25em;

}

Note that :focus-visible support is still rolling out to all browsers, notably missing from Safari. If you would like to try using it, here is an example of including it as a progressive enhancement:

&:focus {

outline: max(1px, 0.1em) dashed currentColor;

outline-offset: -0.25em;

}

@supports selector(:focus-visible) {

&:focus {

outline: none;

}

&:focus-visible {

outline: max(1px, 0.1em) dashed currentColor;

outline-offset: -0.25em;

}

}Hey there! Early bird registration is available for my upcoming July workshop with Smashing Conference - Level-Up With Modern CSS

Focus vs. Source Order#

Another focus related criterion is Success Criterion 2.4.3: Focus Order. For both visual and non-visual users, the focus order - which is typically initiated by keyboard tabbing - should proceed logically. Particularly for visual users, the focus order should follow an expected path which usually means following source order.

From the criterion documentation linked previously:

"For example, a screen reader user interacts with the programmatically determined reading order, while a sighted keyboard user interacts with the visual presentation of the Web page. Care should be taken so that the focus order makes sense to both of these sets of users and does not appear to either of them to jump around randomly."

Modern CSS technically provides layout properties to re-arrange visual order into something different than source order. The impact of this is potentially failing the focus order success criterion if there are focusable elements that are being re-arranged into a surprising order.

If you are able, browse the following demo using your tab key and take notice of what you expected to happen versus what actually happened. When you're finished, or if a tab key is not presently an available input for you, check the box to reveal the tab order.

The goal of this section is more to provide awareness of this criterion when you consider how to solve layout challenges. Upcoming in CSS grid is a native "masonry" solution. Unfortunately, it may negatively impact the expected focus order. Similar issues can be created when assigning specific grid areas that don't match source order, as well as customizing item order in flexbox using the order property.

A recent challenge I faced was a list of navigation links that was requested to break into columns. And in this case, the logical tab order would be down one column before moving on to the next column. The catch was that it was a list of items for a single topic, so semantically it would not be ideal to break it into a list per column. Breaking into multiple lists would also misrepresent the number of items for the single topic for users of assistive tech like screen readers which announce the number of items in a list.

Using the following set of CSS grid properties, I was able to arrive at a non-list-breaking solution:

CSS for "List Focus Order Solution With CSS Grid"

ul {

display: grid;

grid-column-gap: 2rem;

grid-row-gap: 1rem;

/* Causes items to be ordered into columns */

grid-auto-flow: column;

/* # required to prevent a column per link */

grid-template-rows: repeat(3, 1fr);

/* Size the columns */

grid-auto-columns: minmax(0, 1fr);

}

The caution here is to be mindful of the space necessary to accommodate the content. In a navigation scenario, content is usually fairly tightly controlled, so this can be a reasonable solution.

Manuel Matuzovic has an excellent and more thorough guide to considerations of CSS Grid layout and altering source order.

Desktop Zoom and Reflow#

You've tested across viewport sizes using browser dev tools as well as on real mobile devices, and you're happy with your site's responsive behavior. But you're probably missing one test point: desktop zoom.

In the previous tutorial, we started to look at WCAG Success Criterion 1.4.10 - Reflow.

Reflow is the term for supporting desktop zoom up to 400%. On a 1280px wide resolution at 400%, the viewport content is equivalent to 320 CSS pixels wide. The intent of a user with this setting is to trigger content to reflow into a single column for ease of reading.

As also noted in the previous tutorial, typically zoom begins to trigger responsive behavior that you may have set using media queries. But there is currently no zoom media query. Consequently, the aspect ratio of a desktop zoomed to 400% can cause reflow issues with your content.

Some examples of possible issues:

- sticky navigation that covers half or more of the viewport

- contained scroll areas that assume a mobile portrait aspect ratio become unscrollable/cut-off

- unwanted results when using fluid typography techniques

- overflow or overlap issues that cut-off content

- margin and padding spacing appearing too large relative to the content size

Without a zoom media query, it can be difficult to devise zoom solutions that are independent of device size assumptions.

However, with modern CSS functions like min() and max(), we have tools to resolve some zoom instances without detracting from the original intent of our assumed mobile design.

Would you like CSS tips in your inbox? Join my newsletter for article updates, CSS tips, and front-end resources!

We previously looked at using min to adjust a grid column that contained an avatar in a way that worked for small, large, and zoomed viewports.

Let's look at resolving vertical spacing. A common practice is for designers to create a pixel ramp for spacing, perhaps based on an 8px unit. So you would perhaps create spacing utilities that look like:

.margin-top-xs {

margin-top: 8px;

}

.margin-top-sm {

margin-top: 16px;

}

.margin-top-md {

margin-top: 32px;

}

.margin-top-lg {

margin-top: 64px;

}

.margin-top-xl {

margin-top: 128px;

}And so on to accommodate for the full range of your ramp. This is usually fine across a standard range of devices. But consider that the xl value of 128px on a desktop zoomed to 400% becomes half the viewport height.

Instead, we can update the upper end of the range to add in min() to select the lowest computed value. This means that for non-zoomed viewports, 128px will be used. And for 400% zoomed viewports, an alternative viewport unit value may be used.

If you are using a desktop, try out zooming to see the effect on the space between the demo elements:

CSS for "Resolving Margin Spacing For Zoom"

section + section {

margin-top: min(128px, 15vh);

}

Section 1

Section 2

Section 3

This technique can potentially be used if you encounter overlap from absolute positioned elements as well.

For more examples of how zoom can effect layout and some modern CSS solutions, check out the recording of CSS Cafe meetup talk about "Modern CSS Solutions to (Previously) Complex Problems"

In the next section we'll see how to query for touch devices. Using that can make for an excellent combo to help determine the context of a user and present an alternate layout for things like sticky navigation or custom scroll areas.

Sizing Interactive Targets#

Our next area is to consider properly sizing interactive targets, where the term "target" comes from Success Criterion 2.5.5: Target Size. From that criterion:

"The intent of this success criterion is to ensure that target sizes are large enough for users to easily activate them, even if the user is accessing content on a small handheld touch screen device, has limited dexterity, or has trouble activating small targets for other reasons. For instance, mice and similar pointing devices can be hard to use for these users, and a larger target will help them activate the target."

Being introduced in WCAG 2.2 is Success Criterion 2.5.8: Pointer Target Spacing. Together, the guidance indicates that generally interactive controls should either:

- have a minimum actual size of 44px; or

- allowed a minimum target size - inclusive of spacing between the control and other elements - of 44px

There are exceptions and additional examples located in the linked resources to help clarify this requirement. Adrian Roselli also provides an excellent overview and history.

In addition to this site, I maintain SmolCSS.dev which explores minimal modern CSS solutions to create layouts and components. The following is an excerpt from one of the demonstrations - "Smol Avatar List Component".

It uses the CSS function max() to ensure that the default display of the avatar link column is at least 44px regardless of the value that may be passed within the --avatar-size value.

.smol-avatar-list {

--avatar-size: 3rem;

--avatar-count: 3;

display: grid;

/* Default to displaying most of the avatar to

enable easier access on touch devices

`max` ensures the WCAG touch target size is

met or exceeded */

grid-template-columns: repeat(

var(--avatar-count),

max(44px, calc(var(--avatar-size) / 1.15))

);

}Then, when a hover-capable device that also is likely to take a "fine" input such as a mouse or stylus is detected, the solution allows the avatars to overlap. This allowance is due to an animation on :hover and :focus - two interactions not available for touch-only devices - that reveals the avatar fully and meets the target size in those states.

This snippet shows the media query that allows that detection:

@media (any-hover: hover) and (any-pointer: fine) {

/* Allow avatars to overlap by shrinking

grid cell width */

}Using device capability detection, we can offer experiences that allow meeting this criterion while also still allowing design flexibility.

Always test solutions with real devices based on data about your real users.

Reducing Motion#

Some of your users may have vestibular disorders and are at risk of headaches or even seizures due to motion and flashing/blinking animations.

There are three main criteria:

- Success Criterion 2.3.1 Three Flashes or Below Threshold - Web pages do not contain anything that flashes more than three times in any one second period, or the flash is below the general flash and red flash thresholds.

- Success Criterion 2.3.2: Three Flashes - Web pages do not contain anything that flashes more than three times in any one second period

- Success Criterion 2.3.3: Animation from Interactions - Motion animation triggered by interaction can be disabled, unless the animation is essential to the functionality or the information being conveyed.

For more comprehensive information, Val Head is a leading expert and has written extensively about this criteria, including this CSS-Tricks article covering the motion-related WCAG criteria.

Modern CSS gives us a media feature query that we can use to test for a users OS-set preference about motion. While your base animations/transitions should meet the flash related thresholds as noted in WCAG criteria, you should prevent them entirely if a user prefers reduced motion.

Here's a quick rule set to globally handle for this, courtesy of Andy Bell's Modern CSS Reset.

/* Remove all animations and transitions

for people that prefer not to see them */

@media (prefers-reduced-motion: reduce) {

*,

*::before,

*::after {

animation-duration: 0.01ms !important;

animation-iteration-count: 1 !important;

transition-duration: 0.01ms !important;

scroll-behavior: auto !important;

}

}Animations are ran once, and any transitions will happen instantly. In some instances, you'll want to plan animations for this possibility to ensure they "freeze" on the desirable frame.

This demo includes a gently pulsing circle unless a user has selected reduced motion.

CSS for "Demo of `prefers-reduced-motion`"

@media (prefers-reduced-motion: reduce) {

div {

animation-duration: 0.01ms !important;

animation-iteration-count: 1 !important;

}

}

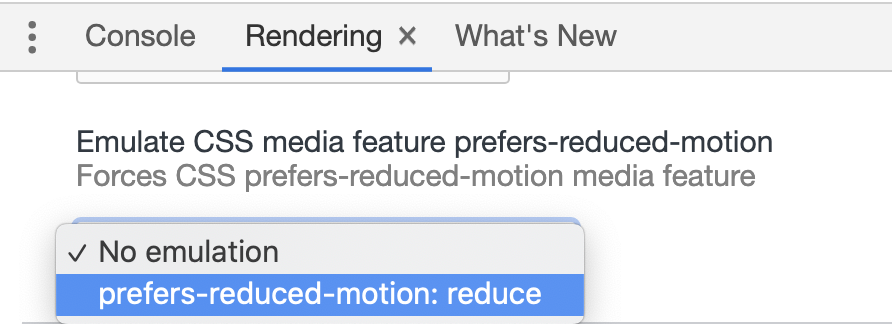

You can test results of this media feature query within Chrome/Edge by opening dev tools and selecting the kebab menu (3 vertical dots), then "More tools" and "Rendering". Then you can toggle settings in the section for "Emulate CSS media feature prefers-reduced motion".

Respecting Color and Contrast Settings#

Dark mode seems to be a fad, but for some users it's essential for ensuring they can read your content. While there are currently no guidelines instructing that both a dark and light mode for content is required, you can begin to be future-friendly by considering offering both modes.

What is a requirement is that if you do offer dark mode that is continues to pass at least the standard color contrast guidelines available in Success Criterion 1.4.3: Contrast (Minimum).

The minimum contrast ratios to meet are at least:

- 4.5:1 for normal text

- 3:1 for large text - defined as 18.66px and bold or larger, or 24px and larger

- 3:1 for graphics and user interface components (such as form input borders)

Head's up: A new color contrast model is being considered for WCAG 3, but it will be a few years before it becomes the standard. You can learn more about the proposed Advanced Perceptual Contrast Algorithm (APCA) in the WCAG 3 draft guidelines (these may change over time until it is standard).

Whether or not you provide dark and light mode, users of Windows 10 devices can select a system setting to enable High Contrast Mode.

In most cases, you should allow the user's settings in this mode to be applied. Occasionally, the application of the high contrast settings means colors that are important to understanding your interface will be removed.

Three often critical properties that will usually be removed in Windows High Contrast Mode:

box-shadowbackground-colorbackground-imageunless it contains aurl()value

And two critical properties that will have their color swapped for the "system color" equivalent:

colorborder-color

You can review a full list of properties affected by this "forced color" mode.

Sometimes these properties can be compensated by using transparent alternates. For example, if you are using box-shadow as an alternate to outline in order to match border-radius on :focus, you should still include an outline with the color value set to transparent as the complement to retain a :focus style for forced color modes. This example is included in my CSS button styling guide. In a similar way, you can include a transparent border in place of box-shadow if the shadow was intended to communicate an important boundary.

If you're using SVG icons, passing currentColor as the value of fill or stroke will help ensure they respond to the forced color settings.

Or, you can use a special media feature query to assign colors from the system color palette. These respect user settings while allowing you to ensure your critical interface elements retain color.

Here's an example of using simple CSS shapes and gradients as icons, and ensuring they retain color within a forced color mode. Within the forced-colors feature query, we only need to set the color property because we've set up the icons to use the currentColor value.

CSS for "Demo of forced-colors"

.icon {

width: 1.5rem;

height: 1.5rem;

display: inline-block;

color: blue;

}

.filled {

background-color: currentColor;

border-radius: 50%;

}

.gradient {

background-image: repeating-linear-gradient(

45deg,

currentColor,

currentColor 2px,

rgba(255, 255, 255, 0) 2px,

rgba(255, 255, 255, 0) 6px

);

border: 1px solid;

}

@media screen and (forced-colors: active) {

.icon {

// Required to enable colors

forced-color-adjust: none;

// User-preferred "text" color

color: CanvasText;

}

}

Using Windows High Contrast Mode, a likely outcome based on defaults would be that the blue becomes white due to the CanvasText color keyword while the page background becomes black.

Review more about how this mode works with a more extensive example on the Microsoft Edge Blog

Accessibility Learning Resources#

While we linked to success criteria and other resources throughout the examples, there is a lot more to learn!

Here are some additional resources to learn more:

- a11y.coffee

- solidstart.info

- This extensive guide about accessible front-end components from Smashing Magazine

- Search and explore the library of resources available from Stark

I've created a variety of resources as well:

- An intro to accessibility from my beginner's webdev series

- Practice resolving issues with my a11y fails project

- Listen to the two part Word Wrap podcast series (that I co-host) on common accessibility failures and WCAG success criteria you may not be meeting

- Learn about handling stateful button contrast and generate an accessible palette with my web app ButtonBuddy

- Use the a11y-color-tokens package to speed up generating an accessible color palette

I enjoy talking about accessibility and do my best to design accessible tutorials and callout any accessibility specifics. If you spot an error or want to suggest an improvement, message me on Twitter.

This content originally appeared on Modern CSS Solutions for Old CSS Problems and was authored by Stephanie Eckles

Stephanie Eckles | Sciencx (2021-04-09T00:00:00+00:00) Modern CSS Upgrades To Improve Accessibility. Retrieved from https://www.scien.cx/2021/04/09/modern-css-upgrades-to-improve-accessibility/

Please log in to upload a file.

There are no updates yet.

Click the Upload button above to add an update.