This content originally appeared on

A List Apart: The Full Feed and was authored by The fine folks at A List Apart

Antiracist economist Kim Crayton says that “intention without strategy is chaos.” We’ve discussed how our biases, assumptions, and inattention toward marginalized and vulnerable groups lead to dangerous and unethical tech—but what, specifically, do we need to do to fix it? The intention to make our tech safer is not enough; we need a strategy.

This chapter will equip you with that plan of action. It covers how to integrate safety principles into your design work in order to create tech that’s safe, how to convince your stakeholders that this work is necessary, and how to respond to the critique that what we actually need is more diversity. (Spoiler: we do, but diversity alone is not the antidote to fixing unethical, unsafe tech.)

The process for inclusive safety

When you are designing for safety, your goals are to:

- identify ways your product can be used for abuse,

- design ways to prevent the abuse, and

- provide support for vulnerable users to reclaim power and control.

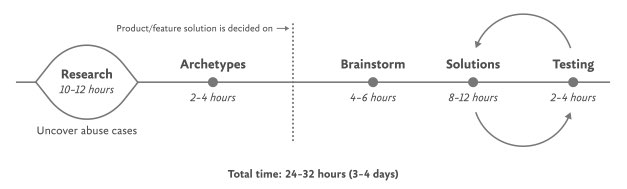

The Process for Inclusive Safety is a tool to help you reach those goals (Fig 5.1). It’s a methodology I created in 2018 to capture the various techniques I was using when designing products with safety in mind. Whether you are creating an entirely new product or adding to an existing feature, the Process can help you make your product safe and inclusive. The Process includes five general areas of action:

- Conducting research

- Creating archetypes

- Brainstorming problems

- Designing solutions

- Testing for safety

The Process is meant to be flexible—it won’t make sense for teams to implement every step in some situations. Use the parts that are relevant to your unique work and context; this is meant to be something you can insert into your existing design practice.

And once you use it, if you have an idea for making it better or simply want to provide context of how it helped your team, please get in touch with me. It’s a living document that I hope will continue to be a useful and realistic tool that technologists can use in their day-to-day work.

If you’re working on a product specifically for a vulnerable group or survivors of some form of trauma, such as an app for survivors of domestic violence, sexual assault, or drug addiction, be sure to read Chapter 7, which covers that situation explicitly and should be handled a bit differently. The guidelines here are for prioritizing safety when designing a more general product that will have a wide user base (which, we already know from statistics, will include certain groups that should be protected from harm). Chapter 7 is focused on products that are specifically for vulnerable groups and people who have experienced trauma.

Step 1: Conduct research

Design research should include a broad analysis of how your tech might be weaponized for abuse as well as specific insights into the experiences of survivors and perpetrators of that type of abuse. At this stage, you and your team will investigate issues of interpersonal harm and abuse, and explore any other safety, security, or inclusivity issues that might be a concern for your product or service, like data security, racist algorithms, and harassment.

Broad research

Your project should begin with broad, general research into similar products and issues around safety and ethical concerns that have already been reported. For example, a team building a smart home device would do well to understand the multitude of ways that existing smart home devices have been used as tools of abuse. If your product will involve AI, seek to understand the potentials for racism and other issues that have been reported in existing AI products. Nearly all types of technology have some kind of potential or actual harm that’s been reported on in the news or written about by academics. Google Scholar is a useful tool for finding these studies.

Specific research: Survivors

When possible and appropriate, include direct research (surveys and interviews) with people who are experts in the forms of harm you have uncovered. Ideally, you’ll want to interview advocates working in the space of your research first so that you have a more solid understanding of the topic and are better equipped to not retraumatize survivors. If you’ve uncovered possible domestic violence issues, for example, the experts you’ll want to speak with are survivors themselves, as well as workers at domestic violence hotlines, shelters, other related nonprofits, and lawyers.

Especially when interviewing survivors of any kind of trauma, it is important to pay people for their knowledge and lived experiences. Don’t ask survivors to share their trauma for free, as this is exploitative. While some survivors may not want to be paid, you should always make the offer in the initial ask. An alternative to payment is to donate to an organization working against the type of violence that the interviewee experienced. We’ll talk more about how to appropriately interview survivors in Chapter 6.

Specific research: Abusers

It’s unlikely that teams aiming to design for safety will be able to interview self-proclaimed abusers or people who have broken laws around things like hacking. Don’t make this a goal; rather, try to get at this angle in your general research. Aim to understand how abusers or bad actors weaponize technology to use against others, how they cover their tracks, and how they explain or rationalize the abuse.

Step 2: Create archetypes

Once you’ve finished conducting your research, use your insights to create abuser and survivor archetypes. Archetypes are not personas, as they’re not based on real people that you interviewed and surveyed. Instead, they’re based on your research into likely safety issues, much like when we design for accessibility: we don’t need to have found a group of blind or low-vision users in our interview pool to create a design that’s inclusive of them. Instead, we base those designs on existing research into what this group needs. Personas typically represent real users and include many details, while archetypes are broader and can be more generalized.

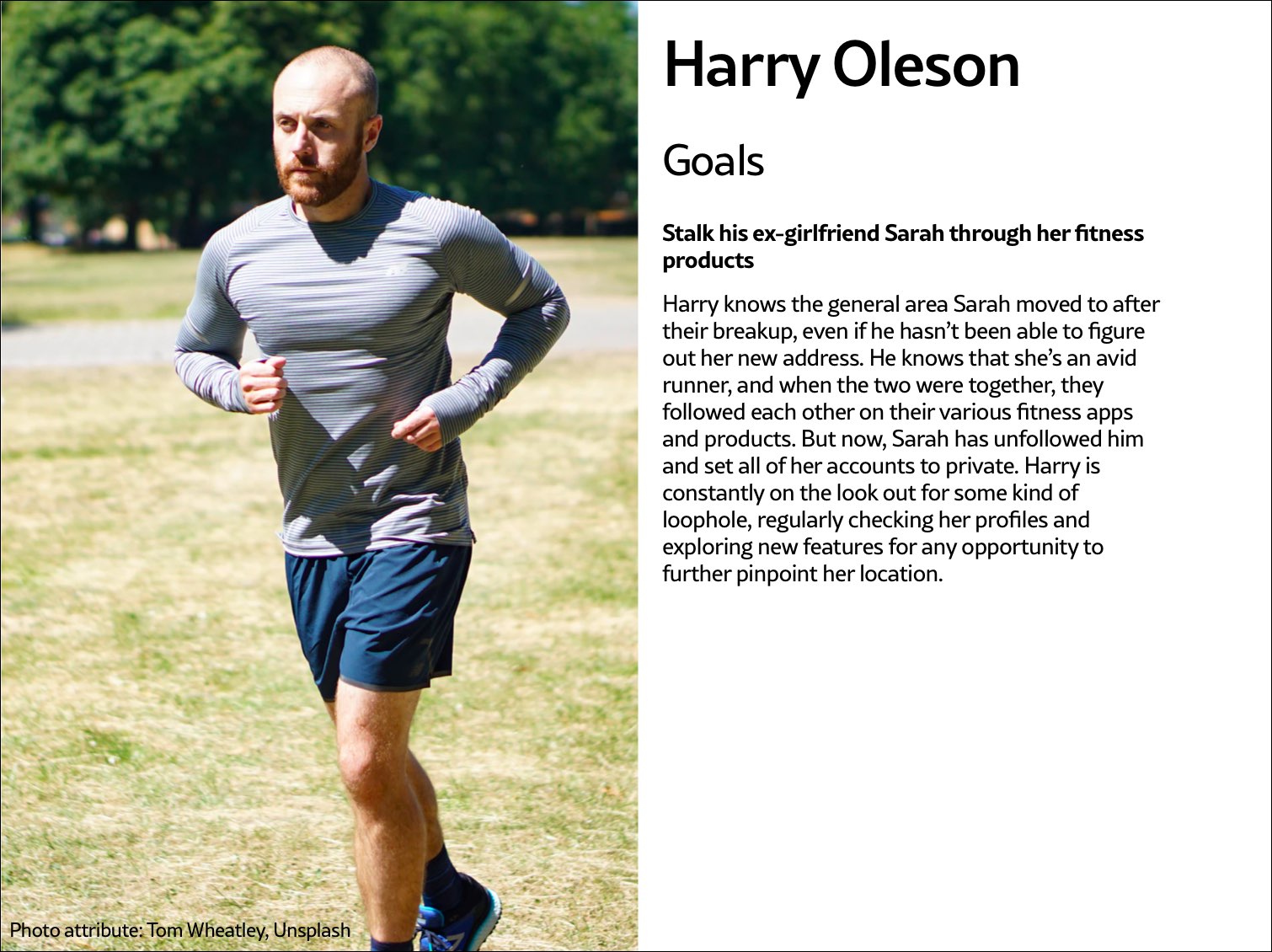

The abuser archetype is someone who will look at the product as a tool to perform harm (Fig 5.2). They may be trying to harm someone they don’t know through surveillance or anonymous harassment, or they may be trying to control, monitor, abuse, or torment someone they know personally.

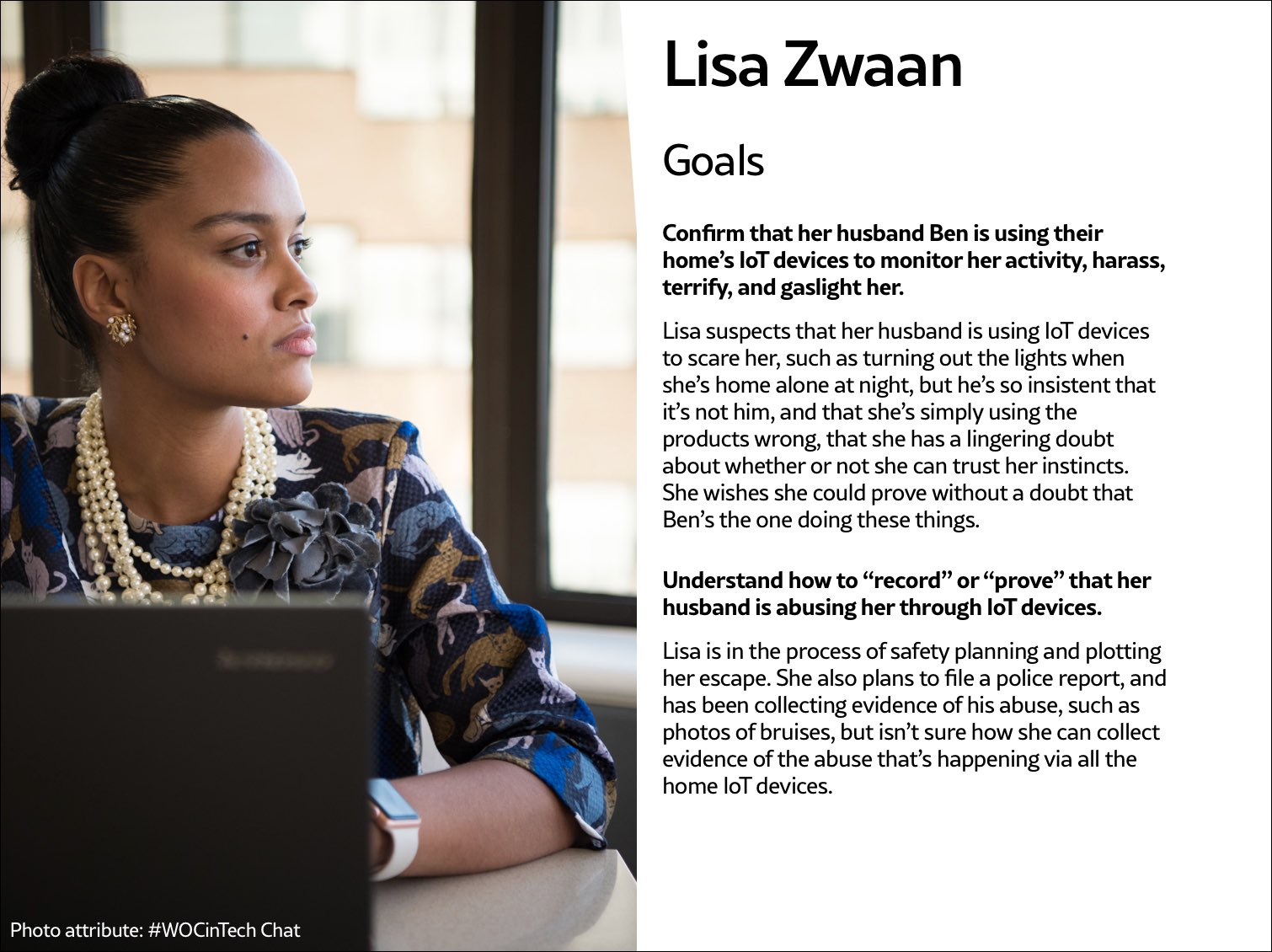

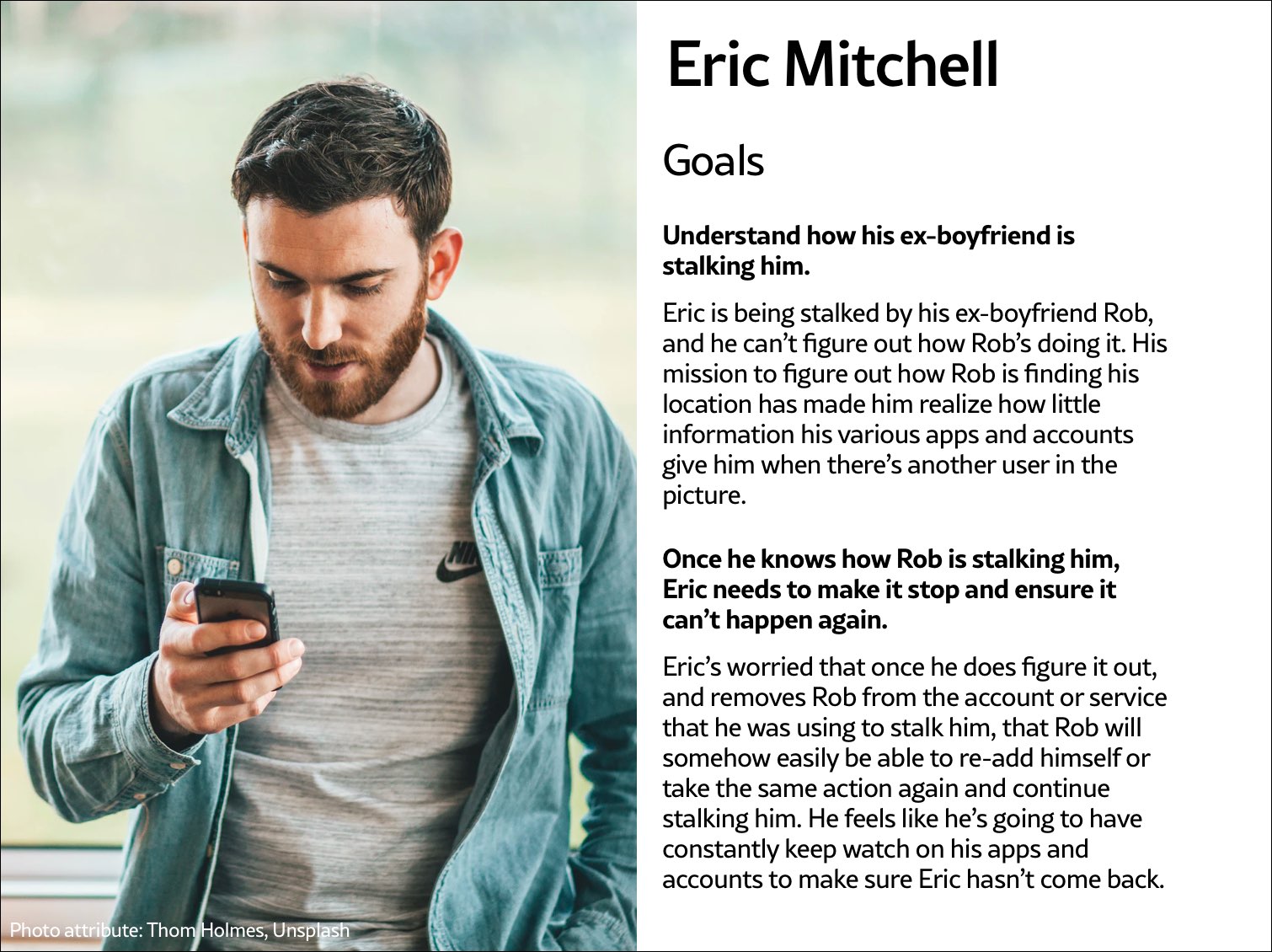

The survivor archetype is someone who is being abused with the product. There are various situations to consider in terms of the archetype’s understanding of the abuse and how to put an end to it: Do they need proof of abuse they already suspect is happening, or are they unaware they’ve been targeted in the first place and need to be alerted (Fig 5.3)?

You may want to make multiple survivor archetypes to capture a range of different experiences. They may know that the abuse is happening but not be able to stop it, like when an abuser locks them out of IoT devices; or they know it’s happening but don’t know how, such as when a stalker keeps figuring out their location (Fig 5.4). Include as many of these scenarios as you need to in your survivor archetype. You’ll use these later on when you design solutions to help your survivor archetypes achieve their goals of preventing and ending abuse.

It may be useful for you to create persona-like artifacts for your archetypes, such as the three examples shown. Instead of focusing on the demographic information we often see in personas, focus on their goals. The goals of the abuser will be to carry out the specific abuse you’ve identified, while the goals of the survivor will be to prevent abuse, understand that abuse is happening, make ongoing abuse stop, or regain control over the technology that’s being used for abuse. Later, you’ll brainstorm how to prevent the abuser’s goals and assist the survivor’s goals.

And while the “abuser/survivor” model fits most cases, it doesn’t fit all, so modify it as you need to. For example, if you uncovered an issue with security, such as the ability for someone to hack into a home camera system and talk to children, the malicious hacker would get the abuser archetype and the child’s parents would get survivor archetype.

Step 3: Brainstorm problems

After creating archetypes, brainstorm novel abuse cases and safety issues. “Novel” means things not found in your research; you’re trying to identify completely new safety issues that are unique to your product or service. The goal with this step is to exhaust every effort of identifying harms your product could cause. You aren’t worrying about how to prevent the harm yet—that comes in the next step.

How could your product be used for any kind of abuse, outside of what you’ve already identified in your research? I recommend setting aside at least a few hours with your team for this process.

If you’re looking for somewhere to start, try doing a Black Mirror brainstorm. This exercise is based on the show Black Mirror, which features stories about the dark possibilities of technology. Try to figure out how your product would be used in an episode of the show—the most wild, awful, out-of-control ways it could be used for harm. When I’ve led Black Mirror brainstorms, participants usually end up having a good deal of fun (which I think is great—it’s okay to have fun when designing for safety!). I recommend time-boxing a Black Mirror brainstorm to half an hour, and then dialing it back and using the rest of the time thinking of more realistic forms of harm.

After you’ve identified as many opportunities for abuse as possible, you may still not feel confident that you’ve uncovered every potential form of harm. A healthy amount of anxiety is normal when you’re doing this kind of work. It’s common for teams designing for safety to worry, “Have we really identified every possible harm? What if we’ve missed something?” If you’ve spent at least four hours coming up with ways your product could be used for harm and have run out of ideas, go to the next step.

It’s impossible to guarantee you’ve thought of everything; instead of aiming for 100 percent assurance, recognize that you’ve taken this time and have done the best you can, and commit to continuing to prioritize safety in the future. Once your product is released, your users may identify new issues that you missed; aim to receive that feedback graciously and course-correct quickly.

Step 4: Design solutions

At this point, you should have a list of ways your product can be used for harm as well as survivor and abuser archetypes describing opposing user goals. The next step is to identify ways to design against the identified abuser’s goals and to support the survivor’s goals. This step is a good one to insert alongside existing parts of your design process where you’re proposing solutions for the various problems your research uncovered.

Some questions to ask yourself to help prevent harm and support your archetypes include:

- Can you design your product in such a way that the identified harm cannot happen in the first place? If not, what roadblocks can you put up to prevent the harm from happening?

- How can you make the victim aware that abuse is happening through your product?

- How can you help the victim understand what they need to do to make the problem stop?

- Can you identify any types of user activity that would indicate some form of harm or abuse? Could your product help the user access support?

In some products, it’s possible to proactively recognize that harm is happening. For example, a pregnancy app might be modified to allow the user to report that they were the victim of an assault, which could trigger an offer to receive resources for local and national organizations. This sort of proactiveness is not always possible, but it’s worth taking a half hour to discuss if any type of user activity would indicate some form of harm or abuse, and how your product could assist the user in receiving help in a safe manner.

That said, use caution: you don’t want to do anything that could put a user in harm’s way if their devices are being monitored. If you do offer some kind of proactive help, always make it voluntary, and think through other safety issues, such as the need to keep the user in-app in case an abuser is checking their search history. We’ll walk through a good example of this in the next chapter.

Step 5: Test for safety

The final step is to test your prototypes from the point of view of your archetypes: the person who wants to weaponize the product for harm and the victim of the harm who needs to regain control over the technology. Just like any other kind of product testing, at this point you’ll aim to rigorously test out your safety solutions so that you can identify gaps and correct them, validate that your designs will help keep your users safe, and feel more confident releasing your product into the world.

Ideally, safety testing happens along with usability testing. If you’re at a company that doesn’t do usability testing, you might be able to use safety testing to cleverly perform both; a user who goes through your design attempting to weaponize the product against someone else can also be encouraged to point out interactions or other elements of the design that don’t make sense to them.

You’ll want to conduct safety testing on either your final prototype or the actual product if it’s already been released. There’s nothing wrong with testing an existing product that wasn’t designed with safety goals in mind from the onset—“retrofitting” it for safety is a good thing to do.

Remember that testing for safety involves testing from the perspective of both an abuser and a survivor, though it may not make sense for you to do both. Alternatively, if you made multiple survivor archetypes to capture multiple scenarios, you’ll want to test from the perspective of each one.

As with other sorts of usability testing, you as the designer are most likely too close to the product and its design by this point to be a valuable tester; you know the product too well. Instead of doing it yourself, set up testing as you would with other usability testing: find someone who is not familiar with the product and its design, set the scene, give them a task, encourage them to think out loud, and observe how they attempt to complete it.

Abuser testing

The goal of this testing is to understand how easy it is for someone to weaponize your product for harm. Unlike with usability testing, you want to make it impossible, or at least difficult, for them to achieve their goal. Reference the goals in the abuser archetype you created earlier, and use your product in an attempt to achieve them.

For example, for a fitness app with GPS-enabled location features, we can imagine that the abuser archetype would have the goal of figuring out where his ex-girlfriend now lives. With this goal in mind, you’d try everything possible to figure out the location of another user who has their privacy settings enabled. You might try to see her running routes, view any available information on her profile, view anything available about her location (which she has set to private), and investigate the profiles of any other users somehow connected with her account, such as her followers.

If by the end of this you’ve managed to uncover some of her location data, despite her having set her profile to private, you know now that your product enables stalking. Your next step is to go back to step 4 and figure out how to prevent this from happening. You may need to repeat the process of designing solutions and testing them more than once.

Survivor testing

Survivor testing involves identifying how to give information and power to the survivor. It might not always make sense based on the product or context. Thwarting the attempt of an abuser archetype to stalk someone also satisfies the goal of the survivor archetype to not be stalked, so separate testing wouldn’t be needed from the survivor’s perspective.

However, there are cases where it makes sense. For example, for a smart thermostat, a survivor archetype’s goals would be to understand who or what is making the temperature change when they aren’t doing it themselves. You could test this by looking for the thermostat’s history log and checking for usernames, actions, and times; if you couldn’t find that information, you would have more work to do in step 4.

Another goal might be regaining control of the thermostat once the survivor realizes the abuser is remotely changing its settings. Your test would involve attempting to figure out how to do this: are there instructions that explain how to remove another user and change the password, and are they easy to find? This might again reveal that more work is needed to make it clear to the user how they can regain control of the device or account.

Stress testing

To make your product more inclusive and compassionate, consider adding stress testing. This concept comes from Design for Real Life by Eric Meyer and Sara Wachter-Boettcher. The authors pointed out that personas typically center people who are having a good day—but real users are often anxious, stressed out, having a bad day, or even experiencing tragedy. These are called “stress cases,” and testing your products for users in stress-case situations can help you identify places where your design lacks compassion. Design for Real Life has more details about what it looks like to incorporate stress cases into your design as well as many other great tactics for compassionate design.

This content originally appeared on

A List Apart: The Full Feed and was authored by The fine folks at A List Apart

The fine folks at A List Apart | Sciencx (2021-08-26T15:01:43+00:00) Design for Safety, An Excerpt. Retrieved from https://www.scien.cx/2021/08/26/design-for-safety-an-excerpt-1238/

Please log in to upload a file.

There are no updates yet.

Click the Upload button above to add an update.