This content originally appeared on DEV Community and was authored by Matt Angelosanto

Written by Mario Zupan ✏️

When we think about P2P technology and what it’s used for nowadays, it’s impossible not to immediately think of blockchain technology. Few topics in IT have been as hyped or as controversial over the last decade as blockchain tech and cryptocurrency.

And while the broad interest in blockchain technology has varied quite a bit — which is, naturally, due to the monetary potential behind some of the more widely known and used cryptocurrencies — one thing is clear: it’s still relevant and it doesn’t seem to be going anywhere.

In a previous article, we covered how to build a very basic, working (albeit rather inefficient) peer-to-peer application in Rust. In this tutorial, we'll demonstrate how to build a blockchain application with a basic mining scheme, consensus, and peer-to-peer networking in just 500 lines of Rust.

We'll cover the following in detail:

- Why blockchain is exciting

- Writing a blockchain app in Rust

- Setting up our Rust app

- Blockchain basics

- Blocks, blocks, blocks

- Which chain to use?

- Mining

- Peer-to-peer basics

- Handling incoming messages

- Putting it all together

- Testing our Rust blockchain

Why blockchain is exciting

While I’m personally not particularly interested in cryptocurrencies or financial gambling in general, I find the idea of decentralizing parts of our existing infrastructure very appealing. There are many great blockchain-based projects out there that aim to tackle societal problems such as climate change, social inequality, privacy and governmental transparency.

The potential behind technology built on the idea of a secure, fully transparent, decentralized ledger that enables actors to interact without having to establish trust first is as game-changing as it seems. It will be exciting to see which of the aforementioned ambitious ideas will get off the ground, gain traction, and succeed going forward.

In short, blockchain technology is exciting, not only for its world-changing potential, but also from a technical perspective. From cryptography over peer-to-peer networking to fancy consensus algorithms, the field has quite a few fascinating topics to dive into.

Writing a blockchain app in Rust

In this guide, we’ll build a very simple blockchain application from scratch using Rust. Our app will not be particularly efficient, secure, or robust, but it will help you understand how some of the fundamental concepts behind widely known blockchain systems can be implemented in a simple way, explaining some of the ideas behind them.

We won’t go into every detail on every concept, and the implementation will have some serious shortcomings. You wouldn’t want to use this project for anything within miles of a production use case, but the goal is to build something you can play around with, apply to your own ideas, and examine to get more familiar with both Rust and blockchain tech in general.

The focus will be on the technical part — i.e., how to implement some of the concepts and how they play together. We won’t explain what a blockchain is, nor will we touch on mining, consensus, and the like beyond what’s necessary for this tutorial. We will mostly be concerned with how to put these ideas, in a simplified version, into Rust code.

Also, we won’t build a cryptocurrency or similar system. Our design is much simpler: every node in the network can add data (strings) to the decentralized ledger (the blockchain) by mining a valid block locally and then broadcasting that block.

As long as it’s a valid block (we’ll see later on what this means), each node will add the block to its chain and our piece of data become part of a decentralized, tamper-proof, indestructible (except that all notes shutdown in our case) network!

This is obviously a quite simplified and somewhat contrived design that would run into efficiency and robustness issues rather quickly when scaling up. But since we’re just doing this exercise to learn, that’s totally fine. If you make it to the end and have some motivation, you can extend it in any direction you want and maybe build the next big thing from our paltry beginnings here — you never know!

Setting up our Rust app

To follow along, all you need is a recent Rust installation.

First, create a new Rust project:

cargo new rust-blockchain-example

cd rust-blockchain-example

Next, edit the Cargo.toml file and add the dependencies you'll need.

[dependencies]

chrono = "0.4"

sha2 = "0.9.8"

serde = {version = "1.0", features = ["derive"] }

serde_json = "1.0"

libp2p = { version = "0.39", features = ["tcp-tokio", "mdns"] }

tokio = { version = "1.0", features = ["io-util", "io-std", "macros", "rt", "rt-multi-thread", "sync", "time"] }

hex = "0.4"

once_cell = "1.5"

log = "0.4"

pretty_env_logger = "0.4"

We’re using libp2p as our peer-to-peer networking layer and Tokio as our underlying runtime.

We’ll use the sha2 library for our sha256 hashing and the hex crate to transform the binary hashes into readable and transferable hex.

Besides that, there’s really only utilities such as serde for JSON, log, and pretty_env_logger for logging, once_cell for static initialization, and chrono for timestamps.

With the setup out of the way, let’s start by implementing the blockchain basics first and then, later on, putting all of it into a P2P-networked context.

Blockchain basics

Let’s first define our data structures for our actual blockchain:

pub struct App {

pub blocks: Vec,

}

#[derive(Serialize, Deserialize, Debug, Clone)]

pub struct Block {

pub id: u64,

pub hash: String,

pub previous_hash: String,

pub timestamp: i64,

pub data: String,

pub nonce: u64,

}

That’s it — not much behind it, really. Our App struct essentially holds our application state. We won’t persist the blockchain in this example, so it will go away once we stop the application.

This state is simply a list of Blocks. We will add new blocks to the end of this list and this will actually be our blockchain data structure.

The actual logic will make this list of blocks a chain of blocks, where each block references the previous block’s hash will be implemented in our application logic. It would be possible to build a data structure that already supports the validation we need out of the box, but this approach seems simpler and we definitely aim for simplicity here.

A Block in our case will consist of an id, which is an index starting at 0 counting up. Then, a sha256 hash (the calculation of which we’ll go into later), the hash of the previous block, a timestamp, the data contained in the block and a nonce, which we will also cover when we talk about mining the block.

Before we get to mining, let’s first implement some of the validation functions we need to keep our state consistent and some of the very basic consensus needed, so each client knows which blockchain is the correct one, in case there are multiple conflicting ones.

We start by implementing our App struct:

impl App {

fn new() -> Self {

Self { blocks: vec![] }

}

fn genesis(&mut self) {

let genesis_block = Block {

id: 0,

timestamp: Utc::now().timestamp(),

previous_hash: String::from("genesis"),

data: String::from("genesis!"),

nonce: 2836,

hash: "0000f816a87f806bb0073dcf026a64fb40c946b5abee2573702828694d5b4c43".to_string(),

};

self.blocks.push(genesis_block);

}

...

}

We initialize our application with an empty chain. Later on, we’ll implement some logic. We ask other nodes on startup for their chain and, if its longer than ours, use theirs. This is our simplistic consensus criteria.

The genesis method creates the first, hard-coded block in our blockchain. This is a “special” block in that it doesn’t really adhere to the same rules as the rest of the blocks. For example, it doesn’t have a valid previous_hash, since there simply was no block before it.

We need this to “bootstrap” our node — or, really, the whole network as the first node starts. The chain has to start somewhere, and this is it.

Blocks, blocks, blocks

Next, let’s add some functionality enabling us to add new blocks to the chain.

impl App {

...

fn try_add_block(&mut self, block: Block) {

let latest_block = self.blocks.last().expect("there is at least one block");

if self.is_block_valid(&block, latest_block) {

self.blocks.push(block);

} else {

error!("could not add block - invalid");

}

}

...

}

Here, we fetch the last block in the chain — our previous block — and then validate whether the block we’d like to add is actually valid. If not, we simply log an error.

In our simple application, we won’t implement any real error handling. As you’ll see later, if we run into trouble with race-conditions between nodes and have an invalid state, our node is basically broken.

I will mention some possible solutions to these problems, but we won’t implement them here; we have quite a bit of ground to cover even without having to worry about these annoying real-world issues.

Let’s look at is_block_valid next, a core piece of our logic.

const DIFFICULTY_PREFIX: &str = "00";

fn hash_to_binary_representation(hash: &[u8]) -> String {

let mut res: String = String::default();

for c in hash {

res.push_str(&format!("{:b}", c));

}

res

}

impl App {

...

fn is_block_valid(&self, block: &Block, previous_block: &Block) -> bool {

if block.previous_hash != previous_block.hash {

warn!("block with id: {} has wrong previous hash", block.id);

return false;

} else if !hash_to_binary_representation(

&hex::decode(&block.hash).expect("can decode from hex"),

)

.starts_with(DIFFICULTY_PREFIX)

{

warn!("block with id: {} has invalid difficulty", block.id);

return false;

} else if block.id != previous_block.id + 1 {

warn!(

"block with id: {} is not the next block after the latest: {}",

block.id, previous_block.id

);

return false;

} else if hex::encode(calculate_hash(

block.id,

block.timestamp,

&block.previous_hash,

&block.data,

block.nonce,

)) != block.hash

{

warn!("block with id: {} has invalid hash", block.id);

return false;

}

true

}

...

}

We first define a constant DIFFICULTY_PREFIX. This is the basis for our very simplistic mining scheme. Essentially, when mining a block, the person mining has to hash the data for the block (with SHA256, in our case) and find a hash, which, in binary, starts with 00 (two zeros). This also denotes our “difficulty” on the network.

As you can imagine, the time to find a suitable hash increases quite a bit if we want three, four, five, or even 20 leading zeros. In a “real” blockchain system, this difficulty would be a network attribute, which is agreed upon between nodes based on a consensus algorithm and based on the network’s hash-power, so the network can guarantee to produce a new block in a certain amount of time.

We won’t deal with this here. For simplicity’s sake, we’ll just hardcode it to two leading zeros. This doesn’t take too long to compute on normal hardware, so we don’t need to worry about waiting too long when testing.

Next, we have a helper function, which is simply the binary representation of a given byte array in the form of a String. This is used to conveniently check whether a hash fits our DIFFICULTY_PREFIX condition. There are, obviously, much more elegant and faster ways to do this, but this is simple and works for our case.

Now to the logic of validating a Block. This is important because it ensures our blockchain adheres to it’s chain property and is hard to tamper with. The difficulty of changing something increases with every block since you’d have to recalculate (i.e., re-mine) the rest of the chain to get a valid chain again. This would be expensive enough to disincentivise you in a real blockchain system)

There are a few rules of thumb you should follow:

- The

previous_hashneeds to actually match the hash of the last block in the chain - The

hashneeds to start with ourDIFFICULTY_PREFIX(i.e., two zeros), which indicated that it was mined correctly - The

idneeds to be the latest ID incremented by 1 - The hash needs to actually be correct; hashing the data of the block needs to give us the block hash (otherwise, you might as well just create a random hash starting with

001)

If we think about this as a distributed system, you might notice that it’s possible to run into trouble here. What if two nodes mine a block at the same time based on block ID 5? They would both create block ID 6 with the previous block pointing to block ID 5.

So then we’d be sent both blocks. We would validate them and add the first one coming in, but the second one would be thrown out during validation since we already have a block with ID 6.

This is an inherent problem in a system such as this and the reason there needs to be a consensus algorithm between nodes to decide which blocks (i.e., which chain) to agree on and use.

Optimally, if the block you mined isn’t added to the agreed -upon chain, you’ll have to mine it again and hope it works better the next time. In our simple case here, this retry mechanism won’t be implemented; if such a race happens, that node is essentially out of the game.

There are more sophisticated approaches to fix this in the blockchain space, of course. For example, if we were to send our data as “transactions” to other nodes and nodes would mine blocks with a set of transactions, this would be somewhat mitigated. But then everyone would mine all the time and the fastest one wins. So, as you can see, this would generate additional, but less severe, problems we’d have to fix.

Anyway, our simple approach will work for our local test network.

Which chain to use?

Now that we can validate a block, let’s implement logic for validating a whole chain:

impl App {

...

fn is_chain_valid(&self, chain: &[Block]) -> bool {

for i in 0..chain.len() {

if i == 0 {

continue;

}

let first = chain.get(i - 1).expect("has to exist");

let second = chain.get(i).expect("has to exist");

if !self.is_block_valid(second, first) {

return false;

}

}

true

}

...

}

Ignoring the genesis block, we basically just go through all the blocks and validate them. If one block fails the validation, we fail the whole chain.

There’s one more method left in App that will help us choose which chain to use:

impl App {

...

// We always choose the longest valid chain

fn choose_chain(&mut self, local: Vec, remote: Vec) -> Vec {

let is_local_valid = self.is_chain_valid(&local);

let is_remote_valid = self.is_chain_valid(&remote);

if is_local_valid && is_remote_valid {

if local.len() >= remote.len() {

local

} else {

remote

}

} else if is_remote_valid && !is_local_valid {

remote

} else if !is_remote_valid && is_local_valid {

local

} else {

panic!("local and remote chains are both invalid");

}

}

}

This happens if we ask another node for its chain to determine whether it’s “better” (according to our consensus algorithm) than our local one.

Our criteria is simply the length of the chain. In real systems, there are usually more factors, such as the difficulty factored in and many other possibilities. For the purpose of this exercise, if a (valid) chain is longer than the other, then we take that one.

We validate both our local and the remote chain and take the longer one. We will also be able to use this functionality during startup when we ask other nodes for their chain and. Since ours only includes a genesis block, we’ll immediately get up to speed with the “agreed on” chain.

Mining

To finish our blockchain-related logic, let’s implement our basic mining scheme.

impl Block {

pub fn new(id: u64, previous_hash: String, data: String) -> Self {

let now = Utc::now();

let (nonce, hash) = mine_block(id, now.timestamp(), &previous_hash, &data);

Self {

id,

hash,

timestamp: now.timestamp(),

previous_hash,

data,

nonce,

}

}

}

When a new block is created, we call mine_block, which will return a nonce and a hash. Then we can create the block with its timestamp, the given data, ID, previous hash, and the new hash and nonce.

We talked about all of the above fields, except for the nonce. To explain what this is, let’s look at the mine_block function:

fn mine_block(id: u64, timestamp: i64, previous_hash: &str, data: &str) -> (u64, String) {

info!("mining block...");

let mut nonce = 0;

loop {

if nonce % 100000 == 0 {

info!("nonce: {}", nonce);

}

let hash = calculate_hash(id, timestamp, previous_hash, data, nonce);

let binary_hash = hash_to_binary_representation(&hash);

if binary_hash.starts_with(DIFFICULTY_PREFIX) {

info!(

"mined! nonce: {}, hash: {}, binary hash: {}",

nonce,

hex::encode(&hash),

binary_hash

);

return (nonce, hex::encode(hash));

}

nonce += 1;

}

}

After announcing that we’re about to mine a block, we set the nonce to 0.

Then, we start an endless loop, which increments the nonce in each step. Inside the loop, besides logging every 100000’s iteration to have a rough progress indicator, we calculate a hash over the data of the block using calculate_hash, which we’ll check out next.

Then, we use our hash_to_binary_representation helper and check whether the calculated hash adheres to our difficulty criteria of starting with two zeros.

If so, we log it and return the nonce, the incrementing integer, where it happened, and the (hex-encoded) hash. Otherwise, we increment nonce and go again.

Essentially, we’re desperately trying to find a piece of data — in this case, the nonce and a number, which, together with our block data hashed using SHA256, will give us a hash starting with two zeros.

We need to record this nonce in our block so other nodes can verify our hash, since the nonce is hashed together with the block data. For example, if it would take us 52,342 iterations to calculate a fitting hash (starting with two zeros), the nonce would be 52341 (1 less, since it starts at 0).

Let’s look at the utility for actually creating the SHA256 hash as well.

fn calculate_hash(id: u64, timestamp: i64, previous_hash: &str, data: &str, nonce: u64) -> Vec<u8> {

let data = serde_json::json!({

"id": id,

"previous_hash": previous_hash,

"data": data,

"timestamp": timestamp,

"nonce": nonce

});

let mut hasher = Sha256::new();

hasher.update(data.to_string().as_bytes());

hasher.finalize().as_slice().to_owned()

}

This one is rather straightforward. We create a JSON-representation of our block data using the current nonce and put it through sha2's SHA256 hasher, returning a Vec<u8>.

That’s essentially all of our blockchain logic implemented. We have a blockchain data structure: a list of blocks. We have blocks, which point to the previous block. Theseare required to have an increasing ID number and a hash that adheres to our rules of mining.

If we ask to get new blocks from other nodes, we validate them and, if they’re OK, add them to the chain. If we get a full blockchain from another node, we also validate it and, if it’s longer than ours (i.e., has more blocks in it), we replace our own chain with it.

As you can imagine, since every node implements this exact logic, blocks and the agreed-on chains can propagate through the network quickly and the network converges to the same state (as with the aforementioned error handling limitations in our simple case).

Peer-to-peer basics

Next, we’ll implement the P2P-based network stack.

Start by creating a p2p.rs file, which will hold most of the peer-to-peer logic we’ll use in our application.

There, again, we define some basic data structures and constants we’ll need:

pub static KEYS: Lazy = Lazy::new(identity::Keypair::generate_ed25519);

pub static PEER_ID: Lazy = Lazy::new(|| PeerId::from(KEYS.public()));

pub static CHAIN_TOPIC: Lazy = Lazy::new(|| Topic::new("chains"));

pub static BLOCK_TOPIC: Lazy = Lazy::new(|| Topic::new("blocks"));

#[derive(Debug, Serialize, Deserialize)]

pub struct ChainResponse {

pub blocks: Vec,

pub receiver: String,

}

#[derive(Debug, Serialize, Deserialize)]

pub struct LocalChainRequest {

pub from_peer_id: String,

}

pub enum EventType {

LocalChainResponse(ChainResponse),

Input(String),

Init,

}

#[derive(NetworkBehaviour)]

pub struct AppBehaviour {

pub floodsub: Floodsub,

pub mdns: Mdns,

#[behaviour(ignore)]

pub response_sender: mpsc::UnboundedSender,

#[behaviour(ignore)]

pub init_sender: mpsc::UnboundedSender,

#[behaviour(ignore)]

pub app: App,

}

Starting from the top, we define a key pair and a derived peer ID. Those are simply libp2p’s intrinsics for identifying a client on the network.

Then, we define two so-called topics: chains and blocks. We’ll use the FloodSub protocol, a simple publish/subscribe protocol, for communication between the nodes.

This has the advantage, that it’s very simple to set up and use, but the disadvantage, that we need to broadcast every piece of information. So even if we just want to respond to one client’s “request for our chain”, that client will send this request to all nodes they’re connected to on the network and we will also send our response to all of them.

This is no problem in terms of correctness, but in terms of efficiency, it’s obviously horrendous. This could be handled by a simple point-to-point request/response model, which is something libp2p supports, but this would simply add even more complexity to this already complex example. If you’re interested, you can check out the libp2p docs.

We could also use the more efficient GossipSub instead of FloodSub. But, again, it’s not as convenient to set up and we’re really not particularly interested in performance at this point. The interface is very similar. Again, if you’re interested in playing around with this, check out the official docs.

Anyway, the topics are basically “channels” to subscribe to. We can subscribe to “chains” and use them to send our local blockchain to other nodes and to receive theirs. The same is true for “blocks”, which we’ll use to broadcast and receive new blocks.

Next up, we have the concept of a ChainResponse holding a list of blocks and a receiver. This is a struct, which we’ll expect if someone sends us their local blockchain and use to send them our local chain.

The LocalChainRequest is what triggers this interaction. If we send a LocalChainRequest with the peer_id of another node in the system, this will trigger that they send us their chain back, as we’ll see later on.

To handle incoming messages, lazy initialization, and keyboard-input by the client’s user, we define the EventType enum, which will help us send events across the application to keep our application state in sync with incoming and outgoing network traffic.

Finally, the core of the P2P functionality is our AppBehaviour, which implements NetworkBehaviour, libp2p’s concept for implementing a decentralized network stack.

We won’t go into the nitty-gritty here, but my comprehensive libp2p tutorial goes into more detail on this.

The AppBehaviour holds our FloodSub instance for pub/sub communication and and Mdns instance, which will enable us to automatically find other nodes on our local network (but not outside of it).

We also add our blockchain App to this behaviour, as well as channels for sending events for both initialization and request/response communication between parts of the app. We’ll see this in action later on.

Initializing the AppBehaviour is also rather straightforward:

impl AppBehaviour {

pub async fn new(

app: App,

response_sender: mpsc::UnboundedSender,

init_sender: mpsc::UnboundedSender,

) -> Self {

let mut behaviour = Self {

app,

floodsub: Floodsub::new(*PEER_ID),

mdns: Mdns::new(Default::default())

.await

.expect("can create mdns"),

response_sender,

init_sender,

};

behaviour.floodsub.subscribe(CHAIN_TOPIC.clone());

behaviour.floodsub.subscribe(BLOCK_TOPIC.clone());

behaviour

}

}

Handling incoming messages

First, we implement the handlers for data coming in from other nodes.

We’ll start with the Mdns events since they’re basically boilerplate:

impl NetworkBehaviourEventProcess<MdnsEvent> for AppBehaviour {

fn inject_event(&mut self, event: MdnsEvent) {

match event {

MdnsEvent::Discovered(discovered_list) => {

for (peer, _addr) in discovered_list {

self.floodsub.add_node_to_partial_view(peer);

}

}

MdnsEvent::Expired(expired_list) => {

for (peer, _addr) in expired_list {

if !self.mdns.has_node(&peer) {

self.floodsub.remove_node_from_partial_view(&peer);

}

}

}

}

}

}

If a new node is discovered, we add it to our FloodSub list of nodes so we can communicate. Once it expires, we remove it again.

More interesting is the implementation of the NetworkBehaviour for our FloodSub communication protocol.

// incoming event handler

impl NetworkBehaviourEventProcess for AppBehaviour {

fn inject_event(&mut self, event: FloodsubEvent) {

if let FloodsubEvent::Message(msg) = event {

if let Ok(resp) = serde_json::from_slice::(&msg.data) {

if resp.receiver == PEER_ID.to_string() {

info!("Response from {}:", msg.source);

resp.blocks.iter().for_each(|r| info!("{:?}", r));

self.app.blocks = self.app.choose_chain(self.app.blocks.clone(), resp.blocks);

}

} else if let Ok(resp) = serde_json::from_slice::(&msg.data) {

info!("sending local chain to {}", msg.source.to_string());

let peer_id = resp.from_peer_id;

if PEER_ID.to_string() == peer_id {

if let Err(e) = self.response_sender.send(ChainResponse {

blocks: self.app.blocks.clone(),

receiver: msg.source.to_string(),

}) {

error!("error sending response via channel, {}", e);

}

}

} else if let Ok(block) = serde_json::from_slice::(&msg.data) {

info!("received new block from {}", msg.source.to_string());

self.app.try_add_block(block);

}

}

}

}

For incoming events, which are FloodsubEvent::Message, we check whether the payload fits any of our expected data structures.

If it’s a ChainResponse, it means we got sent a local blockchain by another node.

We check wether we’re actually the receiver of said piece of data and, if so, log the incoming blockchain and attempt to execute our consensus. If it’s valid and longer than our chain, we replace our chain with it. Otherwise, we keep our own chain.

If the incoming data is a LocalChainRequest, we check whether we’re the ones they want the chain from, checking the from_peer_id. If so, we simply send them a JSON version of our local blockchain. The actual sending part is in another part of the code, but for now, we simply send it through our event channel for responses.

Finally, if it’s a Block that’s incoming, that means someone else mined a block and wants us to add it to our local chain. We check whether the block is valid and, if it is, add it.

Putting it all together

Great! Now let’s wire this all together and add some commands for users to interact with the application.

Back in main.rs, it’s time to actually implement the main function.

We start with the setup:

#[tokio::main]

async fn main() {

pretty_env_logger::init();

info!("Peer Id: {}", p2p::PEER_ID.clone());

let (response_sender, mut response_rcv) = mpsc::unbounded_channel();

let (init_sender, mut init_rcv) = mpsc::unbounded_channel();

let auth_keys = Keypair::::new()

.into_authentic(&p2p::KEYS)

.expect("can create auth keys");

let transp = TokioTcpConfig::new()

.upgrade(upgrade::Version::V1)

.authenticate(NoiseConfig::xx(auth_keys).into_authenticated())

.multiplex(mplex::MplexConfig::new())

.boxed();

let behaviour = p2p::AppBehaviour::new(App::new(), response_sender, init_sender.clone()).await;

let mut swarm = SwarmBuilder::new(transp, behaviour, *p2p::PEER_ID)

.executor(Box::new(|fut| {

spawn(fut);

}))

.build();

let mut stdin = BufReader::new(stdin()).lines();

Swarm::listen_on(

&mut swarm,

"/ip4/0.0.0.0/tcp/0"

.parse()

.expect("can get a local socket"),

)

.expect("swarm can be started");

spawn(async move {

sleep(Duration::from_secs(1)).await;

info!("sending init event");

init_sender.send(true).expect("can send init event");

});

That’s a whole lot of code, but it basically just sets up things we already talked about. We initialize logging and our two event channels for initialization and responses.

Then, we initialize our key pair, the libp2p transport, behavior, and the libp2p Swarm, which is the entity that runs our network stack.

We also initialize a buffered reader on stdin so we can read incoming commands from the user and start our Swarm.

Finally, we spawn an asynchronous coroutine, which waits a second and then sends an initialization trigger on the init channel.

This is the signal we’ll use after starting a node to wait for a bit until the node is up and connected. We then ask another node for their current blockchain to get us up to speed.

The rest of main is the interesting part — the part where we handle keyboard events from the user, incoming data, and outgoing data.

loop {

let evt = {

select! {

line = stdin.next_line() => Some(p2p::EventType::Input(line.expect("can get line").expect("can read line from stdin"))),

response = response_rcv.recv() => {

Some(p2p::EventType::LocalChainResponse(response.expect("response exists")))

},

_init = init_rcv.recv() => {

Some(p2p::EventType::Init)

}

event = swarm.select_next_some() => {

info!("Unhandled Swarm Event: {:?}", event);

None

},

}

};

if let Some(event) = evt {

match event {

p2p::EventType::Init => {

let peers = p2p::get_list_peers(&swarm);

swarm.behaviour_mut().app.genesis();

info!("connected nodes: {}", peers.len());

if !peers.is_empty() {

let req = p2p::LocalChainRequest {

from_peer_id: peers

.iter()

.last()

.expect("at least one peer")

.to_string(),

};

let json = serde_json::to_string(&req).expect("can jsonify request");

swarm

.behaviour_mut()

.floodsub

.publish(p2p::CHAIN_TOPIC.clone(), json.as_bytes());

}

}

p2p::EventType::LocalChainResponse(resp) => {

let json = serde_json::to_string(&resp).expect("can jsonify response");

swarm

.behaviour_mut()

.floodsub

.publish(p2p::CHAIN_TOPIC.clone(), json.as_bytes());

}

p2p::EventType::Input(line) => match line.as_str() {

"ls p" => p2p::handle_print_peers(&swarm),

cmd if cmd.starts_with("ls c") => p2p::handle_print_chain(&swarm),

cmd if cmd.starts_with("create b") => p2p::handle_create_block(cmd, &mut swarm),

_ => error!("unknown command"),

},

}

}

}

We start an endless loop and use Tokio’s select! macro to race multiple async functions.

This means whichever one of these finishes first will get handled first and then we start anew.

The first event emitter is our buffered reader, which will give us input lines from the user. If we get one, we create an EventType::Input with the line.

Then, we listen to the response channel and the init channel, creating their events respectively. And if events come in on the swarm itself, this means they are events that are neither handled by our Mdns behavior nor our FloodSub behavior and we just log them. They’re mostly noise, such as connection/disconnection in our case, but helpful for debugging.

With the corresponding events created (or no event created), we go about handling them.

For our Init event, we call genesis() on our app, creating our genesis block. If we’re connected to nodes, we trigger a LocalChainRequest to the last one in the list.

Obviously, here it would make sense to ask multiple nodes, and maybe multiple times, and select the best (i.e., longest) chain of the responses we get. But for simplicity’s sake, we just ask one and accept whatever they send us.

Then, if we get a LocalChainResponse event, that means something was sent on the response channel. If you remember above, that happened in our FloodSub behavior when we sent back our local blockchain to a requesting node. Here, we actually send the incoming JSON to the correct FloodSub topic, so it’s broadcast to the network.

Finally, for user input, we have three commands:

-

ls plists all peers -

ls cprints the local blockchain -

create b $datacreates a new block with$dataas it’s string content

Each command calls one of these helper functions:

pub fn get_list_peers(swarm: &Swarm) -> Vec {

info!("Discovered Peers:");

let nodes = swarm.behaviour().mdns.discovered_nodes();

let mut unique_peers = HashSet::new();

for peer in nodes {

unique_peers.insert(peer);

}

unique_peers.iter().map(|p| p.to_string()).collect()

}

pub fn handle_print_peers(swarm: &Swarm) {

let peers = get_list_peers(swarm);

peers.iter().for_each(|p| info!("{}", p));

}

pub fn handle_print_chain(swarm: &Swarm) {

info!("Local Blockchain:");

let pretty_json =

serde_json::to_string_pretty(&swarm.behaviour().app.blocks).expect("can jsonify blocks");

info!("{}", pretty_json);

}

pub fn handle_create_block(cmd: &str, swarm: &mut Swarm) {

if let Some(data) = cmd.strip_prefix("create b") {

let behaviour = swarm.behaviour_mut();

let latest_block = behaviour

.app

.blocks

.last()

.expect("there is at least one block");

let block = Block::new(

latest_block.id + 1,

latest_block.hash.clone(),

data.to_owned(),

);

let json = serde_json::to_string(&block).expect("can jsonify request");

behaviour.app.blocks.push(block);

info!("broadcasting new block");

behaviour

.floodsub

.publish(BLOCK_TOPIC.clone(), json.as_bytes());

}

}

Listing clients and printing the blockchain is rather straightforward. Creating a block is more interesting.

In that case, we use Block::new to create (and mine) a new block. Once that happens, we JSONify it and broadcast it to the network so others may add it to their chain.

This where we would put some logic for r-trying this. For example, we could add it to a queue and see whether, after a while, our block propagates to the widely agreed-upon blockchain and, if not, get a new copy of the agreed-on chain and mine it again to get it on there. As mentioned above, this design certainly won’t scale to many nodes mining their blocks all the time, but that’s OK for the purpose of this tutorial.

Let’s start it and see if it works!

Testing our Rust blockchain

We can start the application using RUST_LOG=info cargo run. It’s best to actually start multiple instances of it in different terminal windows.

For example, we can start two nodes:

INFO rust_blockchain_example > Peer Id: 12D3KooWJWbGzpdakrDroXuCKPRBqmDW8wYc1U3WzWEydVr2qZNv

And:

INFO rust_blockchain_example > Peer Id: 12D3KooWSXGZJJEnh3tndGEVm6ACQ5pdaPKL34ktmCsUqkqSVTWX

Using ls p in the second app shows us the connection to the first one:

INFO rust_blockchain_example::p2p > Discovered Peers:

INFO rust_blockchain_example::p2p > 12D3KooWJWbGzpdakrDroXuCKPRBqmDW8wYc1U3WzWEydVr2qZNv

Then, we can use ls c to print the genesis block:

INFO rust_blockchain_example::p2p > Local Blockchain:

INFO rust_blockchain_example::p2p > [

{

"id": 0,

"hash": "0000f816a87f806bb0073dcf026a64fb40c946b5abee2573702828694d5b4c43",

"previous_hash": "genesis",

"timestamp": 1636664658,

"data": "genesis!",

"nonce": 2836

}

]

So far, so good. let’s create a block:

create b hello

INFO rust_blockchain_example > mining block...

INFO rust_blockchain_example > nonce: 0

INFO rust_blockchain_example > mined! nonce: 62235, hash: 00008cf68da9f978aa080b7aad93fb4285e3c0dbd85fc21bc7e83e623f9fa922, binary hash: 0010001100111101101000110110101001111110011111000101010101000101111110101010110110010011111110111000010100001011110001111000000110110111101100010111111100001011011110001111110100011111011000101111111001111110101001100010

INFO rust_blockchain_example::p2p > broadcasting new block

On the first node, we see this:

INFO rust_blockchain_example::p2p > received new block from 12D3KooWSXGZJJEnh3tndGEVm6ACQ5pdaPKL34ktmCsUqkqSVTWX

And calling ls c:

INFO rust_blockchain_example::p2p > Local Blockchain:

INFO rust_blockchain_example::p2p > [

{

"id": 0,

"hash": "0000f816a87f806bb0073dcf026a64fb40c946b5abee2573702828694d5b4c43",

"previous_hash": "genesis",

"timestamp": 1636664655,

"data": "genesis!",

"nonce": 2836

},

{

"id": 1,

"hash": "00008cf68da9f978aa080b7aad93fb4285e3c0dbd85fc21bc7e83e623f9fa922",

"previous_hash": "0000f816a87f806bb0073dcf026a64fb40c946b5abee2573702828694d5b4c43",

"timestamp": 1636664772,

"data": " hello",

"nonce": 62235

}

]

The block got added!

Let’s start a third node. It should automatically get this updated chain because it’s longer than its own (only the genesis block).

INFO rust_blockchain_example > Peer Id: 12D3KooWSDyn83pJD4eEg9dvYffceAEcbUkioQvSPY7aCi7J598q

INFO rust_blockchain_example > sending init event

INFO rust_blockchain_example::p2p > Discovered Peers:

INFO rust_blockchain_example > connected nodes: 2

INFO rust_blockchain_example::p2p > Response from 12D3KooWSXGZJJEnh3tndGEVm6ACQ5pdaPKL34ktmCsUqkqSVTWX:

INFO rust_blockchain_example::p2p > Block { id: 0, hash: "0000f816a87f806bb0073dcf026a64fb40c946b5abee2573702828694d5b4c43", previous_hash: "genesis", timestamp: 1636664658, data: "genesis!", nonce: 2836 }

INFO rust_blockchain_example::p2p > Block { id: 1, hash: "00008cf68da9f978aa080b7aad93fb4285e3c0dbd85fc21bc7e83e623f9fa922", previous_hash: "0000f816a87f806bb0073dcf026a64fb40c946b5abee2573702828694d5b4c43", timestamp: 1636664772, data: " hello", nonce: 62235 }

After sending the init event, we requested the second node’s chain and got it.

Calling ls c here shows us the same chain:

INFO rust_blockchain_example::p2p > Local Blockchain:

INFO rust_blockchain_example::p2p > [

{

"id": 0,

"hash": "0000f816a87f806bb0073dcf026a64fb40c946b5abee2573702828694d5b4c43",

"previous_hash": "genesis",

"timestamp": 1636664658,

"data": "genesis!",

"nonce": 2836

},

{

"id": 1,

"hash": "00008cf68da9f978aa080b7aad93fb4285e3c0dbd85fc21bc7e83e623f9fa922",

"previous_hash": "0000f816a87f806bb0073dcf026a64fb40c946b5abee2573702828694d5b4c43",

"timestamp": 1636664772,

"data": " hello",

"nonce": 62235

}

]

Creating a block also works:

create b alsoworks

INFO rust_blockchain_example > mining block...

INFO rust_blockchain_example > nonce: 0

INFO rust_blockchain_example > mined! nonce: 34855, hash: 0000e0bddf4e603da675b92b88e86e25692eaaa8ad20db6ecab5940bdee1fdfd, binary hash: 001110000010111101110111111001110110000011110110100110111010110111001101011100010001110100011011101001011101001101110101010101010100010101101100000110110111101110110010101011010110010100101111011110111000011111110111111101

INFO rust_blockchain_example::p2p > broadcasting new block

Node 1:

INFO rust_blockchain_example::p2p > received new block from 12D3KooWSDyn83pJD4eEg9dvYffceAEcbUkioQvSPY7aCi7J598q

ls c

INFO rust_blockchain_example::p2p > Local Blockchain:

INFO rust_blockchain_example::p2p > [

{

"id": 0,

"hash": "0000f816a87f806bb0073dcf026a64fb40c946b5abee2573702828694d5b4c43",

"previous_hash": "genesis",

"timestamp": 1636664658,

"data": "genesis!",

"nonce": 2836

},

{

"id": 1,

"hash": "00008cf68da9f978aa080b7aad93fb4285e3c0dbd85fc21bc7e83e623f9fa922",

"previous_hash": "0000f816a87f806bb0073dcf026a64fb40c946b5abee2573702828694d5b4c43",

"timestamp": 1636664772,

"data": " hello",

"nonce": 62235

},

{

"id": 2,

"hash": "0000e0bddf4e603da675b92b88e86e25692eaaa8ad20db6ecab5940bdee1fdfd",

"previous_hash": "00008cf68da9f978aa080b7aad93fb4285e3c0dbd85fc21bc7e83e623f9fa922",

"timestamp": 1636664920,

"data": " alsoworks",

"nonce": 34855

}

]

Node 2:

INFO rust_blockchain_example::p2p > received new block from 12D3KooWSDyn83pJD4eEg9dvYffceAEcbUkioQvSPY7aCi7J598q

ls c

INFO rust_blockchain_example::p2p > Local Blockchain:

INFO rust_blockchain_example::p2p > [

{

"id": 0,

"hash": "0000f816a87f806bb0073dcf026a64fb40c946b5abee2573702828694d5b4c43",

"previous_hash": "genesis",

"timestamp": 1636664655,

"data": "genesis!",

"nonce": 2836

},

{

"id": 1,

"hash": "00008cf68da9f978aa080b7aad93fb4285e3c0dbd85fc21bc7e83e623f9fa922",

"previous_hash": "0000f816a87f806bb0073dcf026a64fb40c946b5abee2573702828694d5b4c43",

"timestamp": 1636664772,

"data": " hello",

"nonce": 62235

},

{

"id": 2,

"hash": "0000e0bddf4e603da675b92b88e86e25692eaaa8ad20db6ecab5940bdee1fdfd",

"previous_hash": "00008cf68da9f978aa080b7aad93fb4285e3c0dbd85fc21bc7e83e623f9fa922",

"timestamp": 1636664920,

"data": " alsoworks",

"nonce": 34855

}

]

Great — it works!

You can play around and try to create race conditions (e.g., by increasing the difficulty to three zeros and starting multiple blocks in multiple nodes. You’ll immediately notice some of the flaws of this design, but the basics work. We have a peer-to-peer blockchain application, a real decentralized ledger with basic robustness, built entirely from scratch in Rust. Awesome!

You can find the full example code at GitHub.

Conclusion

In this tutorial, we built a simple, quite limited, but working blockchain application in Rust. Our blockchain app has a very basic mining scheme, consensus, and peer-to-peer networking in just 500 lines of Rust.

Most of this simplicity is thanks to the fantastic libp2p library, which does all the heavy lifting in terms of networking. Clearly, as is always the case in software engineering tutorials, for a production-grade blockchain-application, there are many, many more things to consider and get right.

However, this exercise sets the stage for the topic, explaining some of the basics and showing them off in Rust, so that we can continue this journey by looking at how we would go about building a blockchain application that could actually be used in practice with a framework such as Substrate.

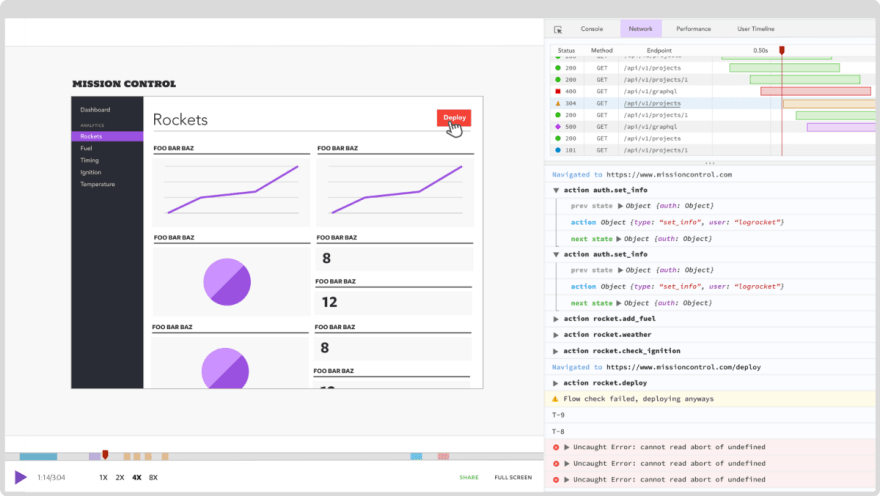

LogRocket: Full visibility into production Rust apps

Debugging Rust applications can be difficult, especially when users experience issues that are difficult to reproduce. If you’re interested in monitoring and tracking performance of your Rust apps, automatically surfacing errors, and tracking slow network requests and load time, try LogRocket.

LogRocket is like a DVR for web apps, recording literally everything that happens on your Rust app. Instead of guessing why problems happen, you can aggregate and report on what state your application was in when an issue occurred. LogRocket also monitors your app’s performance, reporting metrics like client CPU load, client memory usage, and more.

Modernize how you debug your Rust apps — start monitoring for free.

This content originally appeared on DEV Community and was authored by Matt Angelosanto

Matt Angelosanto | Sciencx (2021-12-01T22:05:19+00:00) How to build a blockchain in Rust. Retrieved from https://www.scien.cx/2021/12/01/how-to-build-a-blockchain-in-rust/

Please log in to upload a file.

There are no updates yet.

Click the Upload button above to add an update.