This content originally appeared on Open Culture and was authored by Josh Jones

At least once a day, staff at art museums and galleries worldwide must hear someone say, “the artist must have been on drugs.” It’s the easiest explanation for art that disturbs, unsettles, confounds our expectations of what art should be. Maybe sometimes artists are on drugs. (R. Crumb tells the story of discovering his inimitable style while on acid.) But maybe it’s not the drugs that make their art seem otherworldly. Maybe mind-altering substances make them more receptive to the source of creativity….

In any case, artists have long used psychoactive substances to reach higher states of consciousness and cope with a world that doesn’t get their vision. In the early days of LSD experimentation, one psychiatrist even tested the phenomenon. UC Irvine’s Oscar Janiger dosed volunteer subjects at a rented L.A. house, then had them draw or otherwise record their experiences. He ultimately aimed to make a “creativity pill,” testing hundreds of willing subjects between 1954 and 1962.

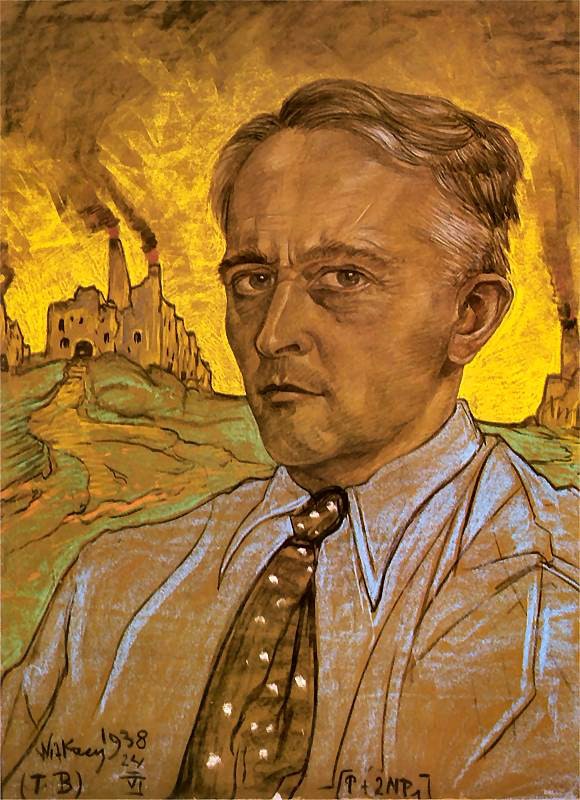

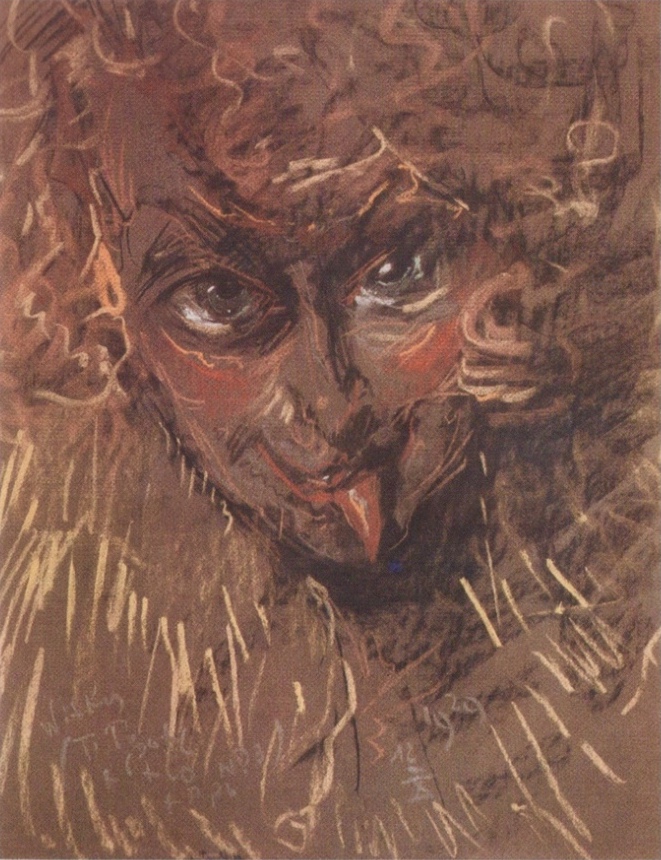

Had Polish artist Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz (1885-1939) — who went by “Witkacy” — lived to see the spread of LSD, he would have signed up for every trial. More likely, he would have conducted his own experiments, with himself as the sole test subject. The Warsaw-born artist, writer, philosopher, novelist, and photographer died in 1939, the year after Swiss chemist Albert Hoffman accidentally synthesized acid. Throughout his career, however, Witkacy experimented with just about every other psychoactive substance, anticipating Janiger by decades with his portraits — painted while… yes… he was on lots of drugs.

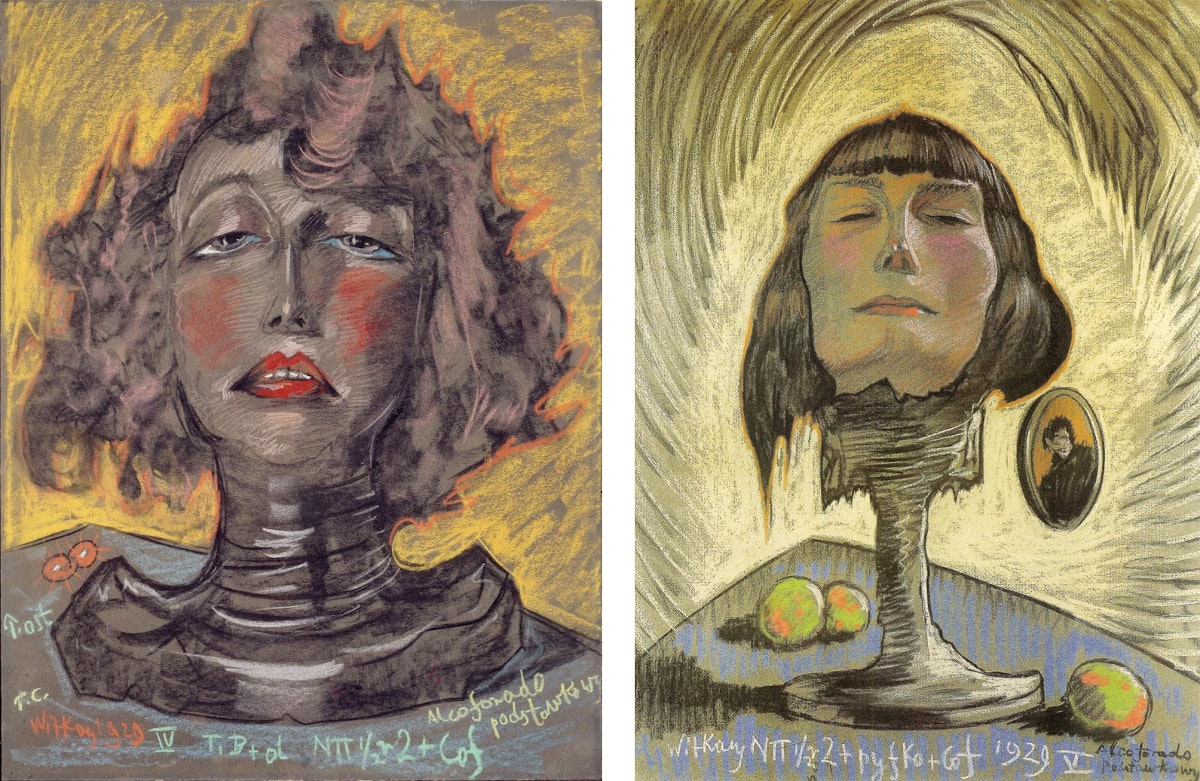

Unlike his contemporary Dalí, Witkacy did not claim to be drugs. But he was hardly coy about their use. He made notes on each painting to indicate his state of intoxication. “Under the influence of cocaine, mescaline, alcohol, and other narcotic cocktails,” the Public Domain Review writes, “Witkacy prepared numerous studies of clients and friends for his portrait painting company, founded in the mid-1920s.” The drugs induced “different approaches to colour, technique, and composition. The resulting images are surreal — and occasionally horrific.” Sometimes the drugs in question were limited to caffeine, a daily staple of artists everywhere. He also made portraits while abstaining from other addictive substances like nicotine and alcohol.

At other times, Witkacy’s notes — written in a kind of code — specified more pronounced usage. He made the portrait above, of Nina Starchurska, in 1929 while on “narcotics of a superior grade,” including mescaline synthesized by Merck and “cocaine + caffeine + cocaine + caffeine + cocaine.” Another portrait of Starchurska (below) made in that same year involved some heavy doses of peyote, among other things.

Witkacy’s investigations were literary as well, culminating in a 1932 book of essays called Narcotics: Nicotine, Alcohol, Cocaine, Peyote, Morphone, Ether + Appendices. The book “owes much to the experimental works of other European psychonauts throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.” Invoking the decadent moralism of Thomas De Quincey and Baudelaire, and it anticipates the utopian, psychedelic prose of Aldous Huxley and Carlos Castaneda.

Where he might fulminate, with satirical edge, against the use of drugs, Witkacy also joyously records their liberating effects on his creative consciousness. His chapter on peyote “most closely approximates the spirit” of his paintings, notes Bibiliokept in a review of the recently republished volume:

“Peyote” begins with Witkiewicz taking his first of seven (!) peyote doses at six in the evening and culminating around eight the following morning with “Straggling visions of iridescent wires.” In increments of about 15 minutes, Witkiewicz notes each of his surreal visions. The wild hallucinations are rendered in equally surreal language: “Mundane disumbilicalment on a cone to the barking of flying canine dragons” here, “The birth of a diamond goldfinch” there.

Elsewhere he writes of “elves on a seesaw (Comedic number)” and “a battle of centaurs turned into a battle between fantastical genitalia,” all of which lead him to conclude, “Goya must have known about peyote.”

Narcotics functions as a kind of key to Witkacy’s thinking as he made the portraits; part drug diary, part artistic statement of purpose, it includes a “List of Symbols” to help decode his shorthand. The artist committed suicide in 1939 when the Red Army invaded Poland. Had he lived to connect with the psychedelic revolution to come, perhaps he would have been the artist to make psychotropic drug use a respectable form of fine art. Then we might imagine conversations in galleries going something like this: “Excuse me, was this artist on drugs?” “Why yes, in fact. She took large doses of psylocybin when she made this. It’s right here in her manifesto…..”

See many more Witkacy portraits at the Public Domain Review.

Related Content:

R. Crumb Describes How He Dropped LSD in the 60s & Instantly Discovered His Artistic Style

Take a Trip to the LSD Museum, the Largest Collection of “Blotter Art” in the World

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

This content originally appeared on Open Culture and was authored by Josh Jones

Josh Jones | Sciencx (2022-05-09T11:00:56+00:00) The Polish Artist Stanisław Witkiewicz Made Portraits While On Different Psychoactive Drugs, and Noted the Drugs on Each Painting. Retrieved from https://www.scien.cx/2022/05/09/the-polish-artist-stanislaw-witkiewicz-made-portraits-while-on-different-psychoactive-drugs-and-noted-the-drugs-on-each-painting/

Please log in to upload a file.

There are no updates yet.

Click the Upload button above to add an update.