This content originally appeared on Level Up Coding - Medium and was authored by Scott White

I recently read Uber’s post Data Race Patterns in Go about runtime analysis of data races in their codebase. This is some amazing work to track down these often subtle bugs and I’m sure Uber’s enormous codebase is benefiting from their hard work. However the tone of the article implies that somehow these issues are the fault of Go and should somehow be prevented by the language itself.

I’ve been programming professionally in Go since 2011, and in that time I’ve never seen a claim by the Go team say concurrency itself is easy. This may be easily confused because there are many presentations about how implementing one concurrency pattern or another is easier in Go than other languages. The difference between “concurrency pattern” and concurrency is that the former has already been validated to be correct and free of bugs. Validating a new concurrency pattern is always hard. The only claims Go makes are that if you know how to correctly implement a concurrency pattern, it will typically be concise and easy to accomplish. Concurrency constructs from other languages like Futures, Promises or async/await all need to be used properly to avoid races. None are magic and all of them have their foot guns. It still requires the skill and expertise to understand and avoid races and deadlocks.

One thing that bothered me about this article was that the examples were overly complicated Go code. It’s hard to say if the examples in the article are real code or not (at least one had a syntax error on my reading), but they did strike me as simplified real code. In any case, the style and organization of the code would get hammered pretty hard in one of our code reviews. I’m not saying things like this don’t slip through on occasion, but I checked our repository usages of concurrency and I didn’t find a single example of concurrent code as complicated as any of these examples. If I had to bet, these examples are outliers at Uber too, but given 50 million lines of code, the outliers will be more extreme than ours. I want to dive deep on each example because I make very different conclusions than the authors.

1. Go’s design choice to transparently capture free variables by reference in goroutines is a recipe for data races

I agree with the authors that closures in Go are a big foot gun because of how they capture scope. I mostly see overuse/abuse of closures in people coming from javascript, and sometimes Java. I almost never use closures in Go unless I need to intentionally capture scope. I have seen similar code to the first example in our code base:

The egregiously unnecessary “end for” comment implies this code has been simplified. But assuming just the code in the example, the fix for this is simple; remove the extra and completely unnecessary closure:

for _, job := range jobs {

go Process(job)

}If we assume the example was simplified and the closure was much bigger, it should have been pulled out into a named function. Named functions are more clear and maintainable and also make the code easier to read. It seems like the style these days is to have lots of fancy closures defined inside your functions. Don’t be fancy.

Examples 2 an 3 in the first pattern also seem to be a complete overuse/abuse of closures and the same rule applies to using named functions instead.

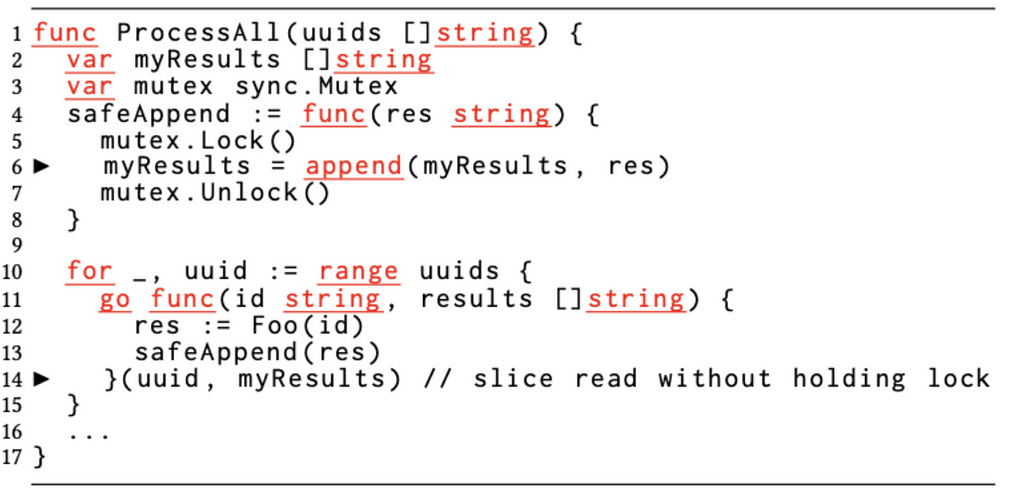

2. Slices are confusing types that create subtle and hard-to-diagnose data races

Pattern 2 is so convoluted that I can’t imagine what the developer was trying to do here. The read/copy that causes the race is to create a variable that is never used. Again, maybe the example removed the usage, but without knowing how the variable is used, it’s impossible to know how to address the issue. I can see the point of the authors here that thinking the copy is safe because they assume a slice is a pointer instead of a struct. But if this convoluted example is the best one they could find, I can’t imagine this happening often. Since this was largest pattern by far, I’d like to know if they all followed the value/reference confusion or something simpler like forgetting to synchronize entirely.

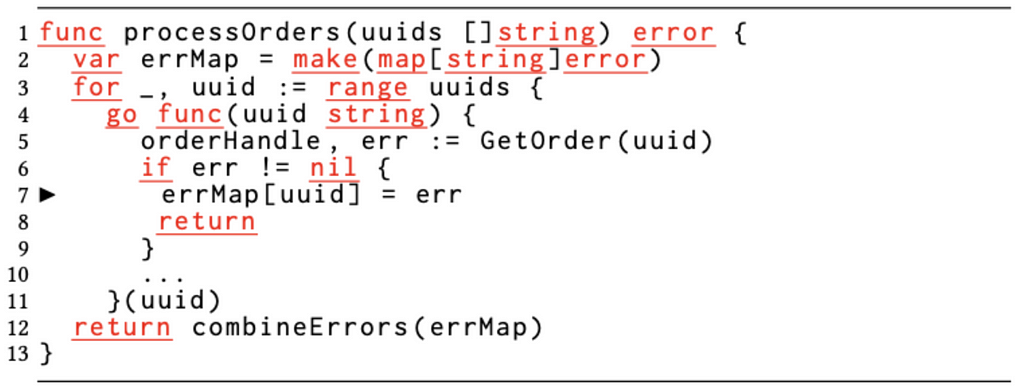

3. Concurrent accesses to Go’s built-in, thread-unsafe maps cause frequent data races

Pattern 3 seems to imply having a map implementation that is not thread safe is somehow a mistake compared to other languages. And having a concise bracket syntax instead of verbose get/set syntax somehow confuses the developer about thread safety. I don’t buy this at all. Early on, Java did a giant switch from Vector which was internally synchronized to ArrayList so single threaded code wouldn’t need to acquire locks. It’s very easy to create a struct to wrap a map and a sync.RWMutex to allow for a concurrent map. Or just use the newer sync.Map if it fits your use case. I just don’t buy that this is harder because of Go’s builtin map or convenient syntax.

4. Go developers often err on the side of pass-by-value (or methods over values), which can cause non-trivial data races

Pattern 4 is a tricky one and I see this mistake made by inexperienced Go programmers frequently. Compared to other languages where copying a struct is always explicit, it’s almost too easy to make copies in Go by passing them to functions. But sync.Mutex’s methods are on the pointer type which is always a hint the pointer should be used. There’s also an explicit warning in the sync.Mutex docs:

A Mutex must not be copied after first use.

There are only three sentences in the documentation on the struct and this is one of them. Seems like something the implementer should be careful about. Once again the solution to the is the same which is to wrap the mutex and protected memory in a struct.

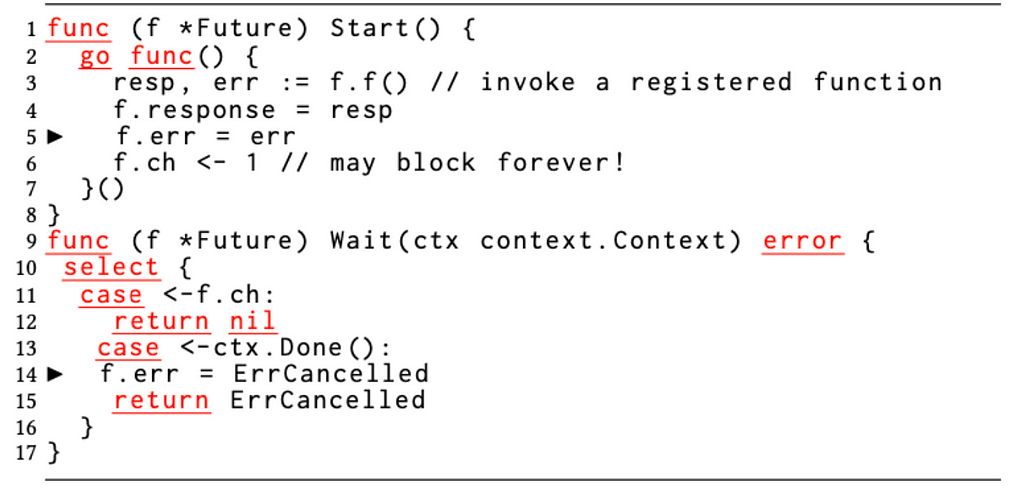

5. Mixed use of message passing (channels) and shared memory makes code complex and susceptible to data races

Pattern 5 illustrates cargo culting a Java concurrency pattern into Go. I see this type of thing with new converts to Go who try to write their favorite concurrency pattern in Go. It’s almost always unnecessary and I’ll spend extra time mentoring to show a better way to accomplish the same effect in a cleaner way in Go. But ignoring that, and just looking at the code, I’m not sure how the authors come to blame channels for unsynchronized variable access. If I had to guess, the author realized later he needed to handle ctx.Done and added it to the Wait without adding synchronization on the err. Since err is private, it seems like there need to be accessors to err not shown in the example which would also be unsynchronized. The authors wanted to somehow blame use of channels here but I don’t follow how one leads to another. The comment that the signal chan could block forever is a completely separate bug that is easily fixed with a buffered channel, but again this points to a likely inexperienced Go programmer.

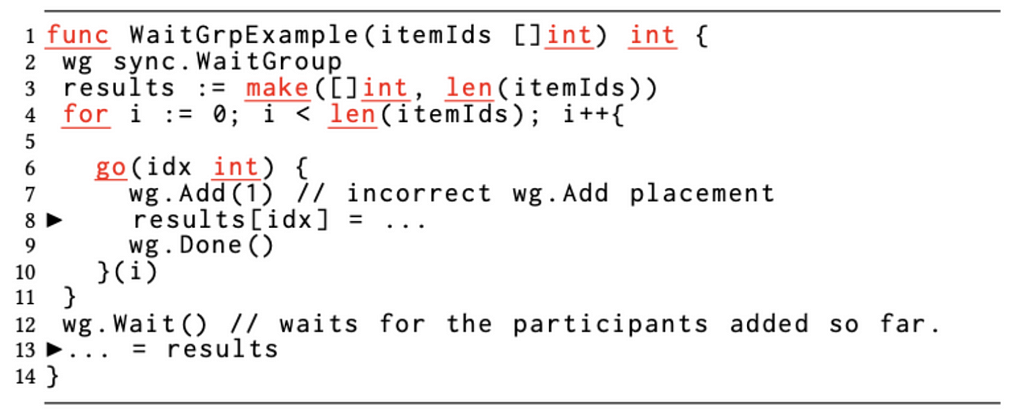

6. Go offers more leeway in its group synchronization construct sync.WaitGroup, but the incorrect placement of Add/Done methods leads to data races

I 100% concur with the authors on Pattern 6. I’ve seen sync.WaitGroup misused in almost exactly the same way as the example. The godocs warn against this and the example clearly shows using Add prior to spawning the goroutine but it’s still easy to make a mistake. Using Add to set the total size outside a loop is my preferred way to use WaitGroup, but I do think having the increment is useful in some circumstances where the final concurrency might not be known prior to the loop. The ordering of defer execution is also something that can lead to subtle bugs (not just races). Both are things to watch out for in code review.

7. Running tests in parallel for Go’s table-driven test suite idiom can often cause data races, either in the product or test code

I don’t know what to say about pattern 7. Seems like making your tests run in parallel without actually making sure your tests are written to run in parallel is a bad idea. I’m gonna just call this a “oops” or “don’t do that” situation.

Conclusions

While I don’t agree with the conclusions of the post, there’s still a lot to learn from these examples. Recognizing common patterns that have higher probability of producing bugs is very valuable process and the authors have certainly done an amazing job. But I’m a woodworker and there’s a saying that goes “a poor craftsman blames his tools.” That isn’t to say some tools are not better than others for accomplishing a task, but it’s up to the implementer to choose wisely. Throughout this article the authors point to certain constructs or language choices that are to blame. At least from the examples, my take is that the developers were often using the wrong tool for the job. It’s impossible to know but there may also some attempts by inexperienced developers building code at the edge of their skill set.

I think if Go is to blame here, it’s because Go encourages more use of concurrency. Developers who are writing concurrency code for the first time need mentoring, and even experienced ones need good code review because concurrency mistakes are easy to make. This isn’t specific to Go; my mental model and approach to break down concurrent code to avoid data races is the same as I did in Java or C. Doing concurrent programming is hard. While Go makes writing concurrent code very concise and readable, the basics still apply. When I teach Go to new developers, I cover concurrency last and say “you won’t need this often” which does sometimes deflate the expectations some devs since they’re often excited to start writing concurrent code in Go.

I do think that the Go community should put less emphasis on the concurrent aspects of Go because, like in any other language, it’s an advanced topic that should be tackled only by experienced developers (or with guidance from one). Most code only requires passing knowledge of concurrency and following a few basic principals like zero or read-only sharing in a concurrent context. It could also be possible that concurrency is easier and more reliable than other languages but we end up with more bugs because more programmers attempt using concurrency than in other languages where the barrier to entry is harder. I don’t think Go should make concurrent code harder to write so only experts bother to attempt using it.

I am very curious to know how often I might see these patterns in my day to day work with Go. If we add up all the bugs they found we get 878 classified races and at the start they said programmers fixed ~1100 total races; which is a big number. But I’m not sure how to put this in perspective because that number doesn’t seem large in considering 50 million lines of code. Our codebase has about 190k lines at the moment and if I extrapolate I should find about 4 of these errors. Luckily at our scale I can check them all manually. I only found 19 uses of the “go” keyword in our codebase and none of them match the patterns here. There might be races I’m not seeing, but not following any of these patterns.

Overall, it’s unclear if these mistakes are common or rare without some normalization. The article states that “Go microservices expose ~8x more concurrency compared to Java microservices” but doesn’t say how it measures concurrency exposure. There also isn’t analysis of errors per opportunity to say that Go is worse/better than other languages.

In defense of Go, there is a huge emphasis on simplicity. The patterns and examples in this article are anything but. Most closures should be one-liners and should be used sparingly compared to other constructs like named functions or structs as containers with methods to properly enforce synchronization. It’s hard to say if the examples are real or not, but most of the mistakes could be avoided, or at least more obvious, if the code itself was less fancy. Go encourages simplicity strongly (and so do I in my team) which is why I suspect many of these mistakes were made by developers new to Go. Recognizing that there’s no magic in Go that makes concurrency somehow easy and striving for the simplest code possible are the ways to avoid mistakes like these.

About me: I’m the Director of Software Architecture at Tonal where we have a 100% Go backend. I’ve been a professional software developer since 1999 and I’ve been using Go since 2011.

Level Up Coding

Thanks for being a part of our community! More content in the Level Up Coding publication.

Follow: Twitter, LinkedIn, Newsletter

Level Up is transforming tech recruiting ➡️ Join our talent collective

Concurrency in Go is Not Magic was originally published in Level Up Coding on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

This content originally appeared on Level Up Coding - Medium and was authored by Scott White

Scott White | Sciencx (2022-06-22T15:16:54+00:00) Concurrency in Go is Not Magic. Retrieved from https://www.scien.cx/2022/06/22/concurrency-in-go-is-not-magic/

Please log in to upload a file.

There are no updates yet.

Click the Upload button above to add an update.