This content originally appeared on DEV Community and was authored by Jacob Kim

Welcome back to Introduction to Data Structures in Go! In this post, we will be looking at trees. So far, we have looked at linear data structures. There was one beginning node and one end node. Data traveled in one direction: either left to right or right to left. Trees are nonlinear, which adds a layer of complexity. Trees are widely used in the programming world for many different purposes, so it is a good idea to get a firm grasp on the topic. You will have no issues with it after reading this post.

Do note that understanding how recursion works will help you immensely when working with trees.

What are trees?

Do you remember what a linked list looked like? Linked lists consisted of several nodes pointing to each other.

HEAD -> Node A -> Node B -> Node C -> nil

A node looked like this:

type Node struct {

data int

next *Node

}

Now imagine a special linked list where there are more than one connections that a node could make. For example, let's say that every node can point to a left node and a right node.

type Node struct {

data int

left *Node

right *Node

}

Or even many nodes:

type Node struct {

data int

adjacent []*Node

}

These nodes become the building blocks of a tree data structure. Trees add more complexity to our typical linked list in the sense that each node can have multiple relations to other nodes. It's not a one-directional relationship like that of arrays, stacks, and queues, which is why it is considered a nonlinear data structure. You can tell that just by looking at a sample diagram:

Image credits to https://static.javatpoint.com/ds/images/tree.png

It looks like an upside-down tree, right?

Properties of a tree

Let's use the above example for this.

-

A tree consists of a root node and zero or more subtrees connected to it.

- A root node is the topmost node of the tree. In the above diagram, John is the root node.

- A subtree is just a tree within a larger tree. You can see how the root node John is connected to two subtrees that each have Steve and Rohan as their root nodes.

- A tree with only one node is still considered a tree.

-

The most important relationship is the parent-children relationship. The parent node is a direct predecessor of a child node. A child node is a direct successor of a parent node.

- In the above diagram, John is the parent node of Steve and Rohan. Lee, Bob, and Ella are the child nodes of Steve.

Sibling nodes are nodes that share a parent node. Steve and Rohan are sibling nodes.

Leaf nodes are nodes that do not have any children. Lee, Bob, Ella, Sal, Bill, and Raj are all leaf nodes.

Ancestor-descendent relationships are like parent-children relationships but on a larger scale. If there exists a way to traverse from B to A, then A is an ancestor of B and B is a descendent of A. Emma is the ancestor of Bill and Tom, and Bill and Tom are descendants of Emma.

The depth of a node is the number of edges between the root and itself. The depth of Tom is 3.

-

The height of a node is the number of edges between itself and the farthest leaf node within its subtree. The level of a node is the number of edges between itself and the root node.

- The height of Rohan is 3, and its level is 1.

The height of a tree is the height of the root node. The height of the tree in the diagram is the height of John, which is 4.

If there are n nodes, then there are n-1 edges.

It's a lot of information, but a lot of these are pretty intuitive.

What is a binary tree?

Now that we know what a tree is, we can look at the most popular type of tree: the binary tree. A binary tree is a tree where each node can have at most two children. Binary trees are very popular in the programming world because it is the backbone of the binary search tree, which provides one of the fastest ways to search through a list of data. It is also easy to implement because there are only two child nodes at maximum.

What is a binary search tree?

A binary search tree is a special type of binary tree. The left child must have a value less than the parent, and the right child must have a value greater than the parent. Binary search trees, abbreviated as BSTs, are used for, well, searching. When we search for an item in a list, we can either iterate through the entire list and stop when we find the item, or perform a binary search: split the list in half, pick the half where the item would be, split again, and vice versa. While a linear search would take O(n) time, a binary search would take O(log n) time, which makes it more efficient. A BST is a representation of such a search algorithm.

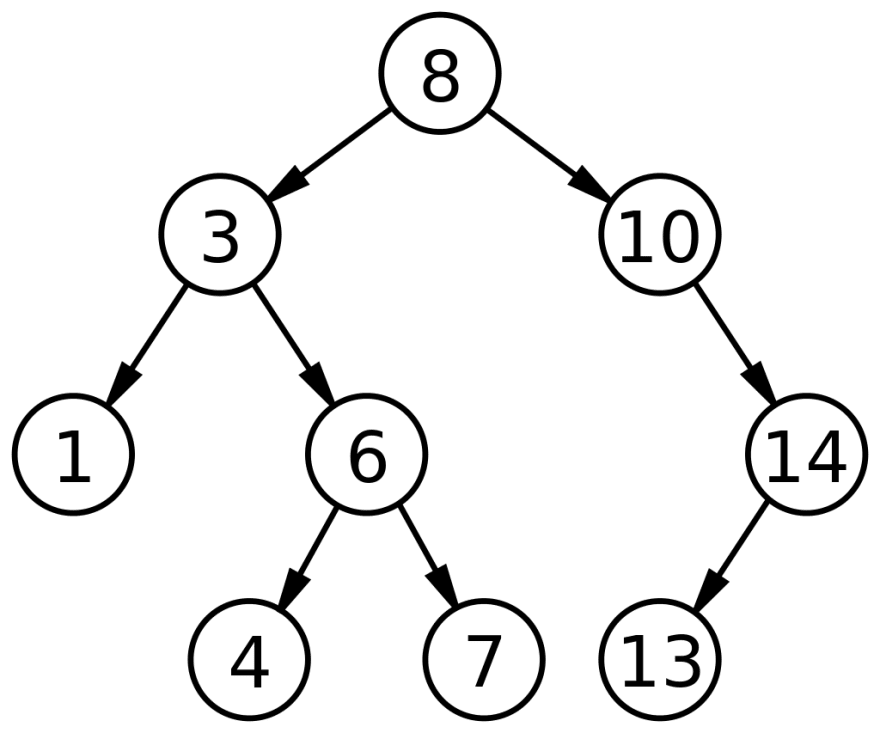

Here is a sample binary search tree.

Image credits to https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/da/Binary_search_tree.svg/1024px-Binary_search_tree.svg.png

Traversing the binary search tree

Because a binary search tree is a nonlinear data structure, there are many ways to traverse it. We will go over the two most popular methods: inorder traversal and level order traversal.

Inorder traversal

Inorder traversal is a depth-first, recursive method that traverses the tree in a left node > root node > right node order. A depth-first approach will poke the deepest leaf nodes in a subtree before moving on to the next subtree. In the example BST above, a full inorder traversal would output this:

1 3 4 6 7 8 10 13 14

For a binary search tree, an inorder traversal will always print the nodes in increasing order.

Level order traversal

Level order traversal takes a breadth-first approach. A breadth-first approach, unlike a depth-first approach, will iterate through the tree level-by-level. A full level order traversal would output this:

8 3 10 1 6 14 4 7 13

Creating a binary search tree in Go

Let's try creating a BST in Go.

package main

import "fmt"

type Node struct {

data int

left *Node

right *Node

}

type BST struct {

root *Node

}

func (bst *BST) Insert(val int) {

bst.InsertRec(bst.root, val)

}

func (bst *BST) InsertRec(node *Node, val int) *Node {

if bst.root == nil {

bst.root = &Node{val, nil, nil}

return bst.root

}

if node == nil {

return &Node{val, nil, nil}

}

if val <= node.data {

node.left = bst.InsertRec(node.left, val)

}

if val > node.data {

node.right = bst.InsertRec(node.right, val)

}

return node

}

func (bst *BST) Search(val int) bool {

found := bst.SearchRec(bst.root, val)

return found

}

func (bst *BST) SearchRec(node *Node, val int) bool {

if node.data == val {

return true

}

if node == nil {

return false

}

if val < node.data {

return bst.SearchRec(node.left, val)

}

if val > node.data {

return bst.SearchRec(node.right, val)

}

return false

}

func (bst *BST) Inorder(node *Node) {

if node == nil {

return

} else {

bst.Inorder(node.left)

fmt.Print(node.data, " ")

bst.Inorder(node.right)

}

}

func (bst *BST) Levelorder() {

if bst.root == nil {

return

}

nodeList := make([](*Node), 0)

nodeList = append(nodeList, bst.root)

for !(len(nodeList) == 0) {

current := nodeList[0]

fmt.Print(current.data, " ")

if current.left != nil {

nodeList = append(nodeList, current.left)

}

if current.right != nil {

nodeList = append(nodeList, current.right)

}

nodeList = nodeList[1:]

}

}

func main() {

bst := BST{}

bst.Insert(10)

bst.Insert(5)

bst.Insert(15)

bst.Insert(20)

bst.Insert(17)

bst.Insert(4)

bst.Insert(6)

bst.Inorder(bst.root)

fmt.Println()

bst.Levelorder()

fmt.Println()

fmt.Println(bst.Search(5))

}

Let's go over each part of the code.

type Node struct {

data int

left *Node

right *Node

}

type BST struct {

root *Node

}

These are the definitions of Node and BST. I like to create a struct for the whole BST instead of just working with a pointer to the root node. In many C and C++ tutorials, you will see the approach of keeping only the pointer to the head or root node. I like to think of a BST as a whole entity, so that's why I'm defining the BST struct. It just makes more sense to me.

func (bst *BST) Insert(val int) {

bst.InsertRec(bst.root, val)

}

func (bst *BST) InsertRec(node *Node, val int) *Node {

if bst.root == nil {

bst.root = &Node{val, nil, nil}

return bst.root

}

if node == nil {

return &Node{val, nil, nil}

}

if val <= node.data {

node.left = bst.InsertRec(node.left, val)

}

if val > node.data {

node.right = bst.InsertRec(node.right, val)

}

return node

}

This is how we will insert a new node. We split the logic into two parts: the Insert function and the InsertRec function that calls itself. The reason why we do this is that InsertRec returns a *Node, but we don't have a use for this in the Insert function.

The InsertRec function might seem convoluted, but we can take it apart. We pass in a pointer to a node, along with the value we want to add. When there are no nodes in our BST, our bst.root will be nil, so it will be set to val. For other cases, we follow a set of conditionals:

If

valis smaller thannode.data, then we callInsertReconnode.left. This will make sure that we go depth-first and reach the leftmost node.We know that when we reach the leftmost leaf node, going any more left will result in

nil. This is where we return&Node{val, nil, nil}.A similar thing happens when

valis greater thannode.data.

func (bst *BST) Search(val int) bool {

found := bst.SearchRec(bst.root, val)

return found

}

func (bst *BST) SearchRec(node *Node, val int) bool {

if node == nil {

return false

}

if node.data == val {

return true

}

if val < node.data {

return bst.SearchRec(node.left, val)

}

if val > node.data {

return bst.SearchRec(node.right, val)

}

return false

}

This is the search function. It wouldn't make sense to not write a search function for a binary search tree. Searching takes a similar approach to insertion in the sense that it also separates its logic into Search and the recursive SearchRec. The logic is also very similar. The only difference is that SearchRec returns a bool and directly compares node.data to val. You also want to do the nil comparisons first, or else you may run into nil pointer dereference panics.

func (bst *BST) Inorder(node *Node) {

if node == nil {

return

} else {

bst.Inorder(node.left)

fmt.Print(node.data, " ")

bst.Inorder(node.right)

}

}

The inorder traversal function also uses... recursion. It burrows deep into the tree's leftmost node first until you can't go any further deeper. Then it prints node.data, then moves on to the right node. You do this from the bottom up until all the nodes are traversed through.

You may have noticed that there are a lot of recursions. Recursion is a confusing topic for many of us, but a lot of methods on trees use recursion. This is because a tree looks a bit like a fractal, where each child node spawns another subtree. Because the shape repeats a lot, it makes sense to use recursive functions on the subtrees. I highly recommend you start with a smaller tree and actually draw out each step to fully understand how recursive functions work. It's really cool, and a good way to learn recursion.

func (bst *BST) Levelorder() {

if bst.root == nil {

return

}

nodeList := make([](*Node), 0)

nodeList = append(nodeList, bst.root)

for !(len(nodeList) == 0) {

current := nodeList[0]

fmt.Print(current.data, " ")

if current.left != nil {

nodeList = append(nodeList, current.left)

}

if current.right != nil {

nodeList = append(nodeList, current.right)

}

nodeList = nodeList[1:]

}

}

Level order traversal is not recursive, because we aren't repeating a certain algorithm over smaller subtrees. Instead, we use a queue to keep track of the nodes we haven't gone through yet. We create a nodeList and push our root node inside. From this point on, until no nodes are left in the nodeList, we print the current node's value, add node.left and node.right into the nodeList, and pop the current node out of the list.

func main() {

bst := BST{}

bst.Insert(10)

bst.Insert(5)

bst.Insert(15)

bst.Insert(20)

bst.Insert(17)

bst.Insert(4)

bst.Insert(6)

bst.Inorder(bst.root)

fmt.Println()

bst.Levelorder()

fmt.Println()

fmt.Println(bst.Search(5))

}

If we run this code, we get the following output:

4 5 6 10 15 17 20

10 5 15 4 6 20 17

true

false

Conclusion

We haven't gone over all concepts of trees, because there are so many applications and concepts. We went over the basic properties and methods using binary search trees. There is so much more to cover, so do expect to see posts on those in the future! You will use trees in many areas. If you are studying networking, you may have heard of the spanning tree protocol that prevents broadcast storms. The spanning tree is a tree consisting of nodes that represent the nodes in your network. Your file system can be represented as trees, as they are hierarchies of files and folders.

Thank you for reading! You can also read this post on Medium and my personal site.

This content originally appeared on DEV Community and was authored by Jacob Kim

Jacob Kim | Sciencx (2022-07-04T02:00:18+00:00) Trees in Go. Retrieved from https://www.scien.cx/2022/07/04/trees-in-go/

Please log in to upload a file.

There are no updates yet.

Click the Upload button above to add an update.