This content originally appeared on Modern CSS Solutions and was authored by Stephanie Eckles

A cross-browser feature as of the release of Firefox 128 in July 2024 is a new at-rule - @property - which allows defining types as well as inheritance and an initial value for your custom properties.

We'll learn when and why traditional fallback values can fail, and how @property features allow us to write safer, more resilient CSS custom property definitions.

Standard Use of Custom Properties

#Custom properties - aka "CSS variables" - are useful because they allow creating references to values similar to variables in other programming languages.

Consider the following scenario which creates and assigns the --color-blue property, which then is implemented as a class and applied to a paragraph.

CSS for "Standard use case for custom properties"

:root {

--color-blue: blue;

}

.color-blue {

color: var(--color-blue);

}

I'm blue dabadee

The paragraph renders as blue. Excellent! Ship it.

Common Error Conditions Using Custom Properties

#Now, you and I both know that "blue" is a color. And it also may seem obvious that you would only apply the class that uses this color to text we intend to be blue.

But, the real world isn't perfect, and sometimes the downstream consumers of our CSS end-up with a reason to re-define the value. Or perhaps they accidentally introduce a typo that impacts the original value.

The outcome of either of these scenarios could be:

- the text ends up a color besides blue, as that author intended

- the text surprisingly renders as black

If the rendered color is surprisingly black, it's likely that we've hit the unique scenario of invalid at computed value time.

When the browser is assessing CSS rules and working out what value to apply to each property based on the cascade, inheritance, specificity and so forth, it will retain a custom property as the winning value as long as it understands the general way it's being used.

In our --color-blue example, the browser definitely understands the color property, so it assumes all will be ok with the use of the variable as well.

But, what happens if someone redefines --color-blue to an invalid color?

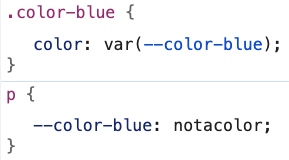

CSS for "Defining an invalid color"

:root {

--color-blue: blue;

}

.color-blue {

color: var(--color-blue);

}

p {

--color-blue: notacolor;

}

I'm blue dabadee (maybe)

Uh oh - it's surprisingly rendering as black.

Why Traditional Fallbacks Can Fail

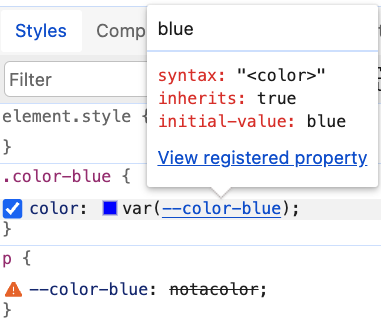

#Ok, before we learn what that scary-sounding phrase means, let's take a look in DevTools and see if it gives us a clue about what's going on.

That looks pretty normal, and doesn't seem to reveal that anything is wrong, making troubleshooting the error a lot trickier.

You might know that custom properties allow a fallback value as second parameter, so perhaps that will help! Let's try.

CSS for "Attempt resolution with custom property fallback"

:root {

--color-blue: blue;

}

.color-blue {

color: var(--color-blue, blue);

}

p {

--color-blue: notacolor;

}

I'm blue dabadee (maybe)

Unfortunately, the text still renders as black.

Ok, but our good friend the cascade exists, and back in the day we used to put things like vendor prefixed properties prior to the unprefixed ones. So, perhaps if we use a similar method and supply an extra color definition before the one that has the custom property it can fallback to that?

CSS for "Attempt resolution with extra color definition"

:root {

--color-blue: blue;

}

.color-blue {

color: blue;

color: var(--color-blue);

}

p {

--color-blue: notacolor;

}

I'm blue dabadee (maybe)

Bummer, we don't seem to be making progress towards preventing this issue.

This is because of the (slightly scary sounding) scenario invalid at computed value time.

Although the browser has kept our definition that expects a custom property value, it's not until later that the browser tries to actually compute that value.

In this case, it looks at both the .color-blue class and the value provided for the p element rule and attempts to apply the computed value of notacolor. At this stage, it has discarded the alternate value of blue originally provided by the class. Consequently, since notacolor is in fact not a color and therefore invalid, the best it can do is use either:

- an inherited value if the property is allowed to inherit and an ancestor has provided a value; or

- the initial value as defined in the CSS spec

While color is an inheritable property, we haven't defined it on any ancestors, so the rendered color of black is due to the initial value.

Refer to this earlier Modern CSS article about how custom property values are computed and learn more deeply about the condition of invalid at computed value time.

Defining Types for Safer CSS

#It's time to introduce @property to help solve this issue of what you may perceive as a surprising rendered value.

The critical features @property provides are:

- defining acceptable types for specific custom properties

- enabling or disabling inheritance

- providing an initial value as a failsafe for invalid or undefined values

This at-rule is defined on a per-custom property basis, meaning a unique definition is needed for each property for which you want to leverage these benefits.

It is not a requirement, and you can certainly continue using custom properties without ever bringing in @property.

Please note that at time of writing,

@propertyis very newly cross-browser and I would advise you to consider it a progressive enhancement to benefit users in supporting browsers.

Let's apply it to our blue dilemma and see how it fixes the issue of the otherwise invalid color supplied in the element rule.

CSS for "Apply @property to --color-blue"

@property --color-blue {

syntax: "<color>";

inherits: true;

initial-value: blue;

}

/* Prior rules also apply */

I'm blue dabadee (maybe)

Success, our text is still blue despite the invalid definition!

Additionally, DevTools is now helpful again:

We can observe both that the invalid value is clearly an error, and we also are provided the full definition of the custom property via the hover overlay.

Providing Types via syntax

#Why would we need types for custom properties? Here are a few reasons:

- types help verify what makes a valid vs. invalid value

- without types, custom properties are very open-ended and can take nearly any value, including a blank space

- lack of types prevents browser DevTools from providing the optimal level of detail about which value is in use for a custom property

In our @property definition, the syntax descriptor enables providing the allowed types for the custom property. We used "<color>", but other types include:

"<length>"- numbers with units attached, ex.4pxor3vw"<integer>"- decimal units 0 through 9 (aka "whole numbers")"<number>"- numbers which may have a fraction, ex.1.25"<percentage>"- numbers with a percentage sign attached, ex.24%"<length-percentage>"- accepts valid<length>or<percentage>values

A special case is "*" which stands for "universal syntax" and enables accepting any value, similar to the default behavior. This means you skip the typing benefit, but perhaps want the inheritance and/or initial value control.

These types and more are listed for the syntax descriptor on MDN.

The type applies to the computed value of the custom property, so the "<color>" type would be happy with both blue as well as light-dark(blue, cyan) (although only one of those is accepted into the initial-value as we will soon learn).

Stronger Typing With Lists

#Let's say we want to provide a little flexibility for our --color-blue custom property.

We can use a list to provide valid options. Anything other than these exact values would be considered invalid, and use the initial-value instead (if inheritance didn't apply). These are called "custom idents", are case sensitive, and can be any value.

CSS for "Defining a list within syntax"

@property --color-blue {

syntax: "blue | cyan | dodgerblue";

inherits: true;

initial-value: blue;

}

.color-blue {

color: var(--color-blue);

}

.demo p {

--color-blue: dodgerblue;

}

I'm blue dabadee (maybe)

Typing for Mixed Values

#The pipe character (|) used in the previous list indicates an "or" condition. While we used explicit color names, it can also be used to say "any of these syntax types are valid."

syntax: "<color> | <length>";Typing for Multiple Values

#So far, we've only typed custom properties that expect a single value.

Two additional cases can be covered with an additional "multiplier" character, which should immediately follow the syntax component name.

- Use

+to support a space-separated list, ex."<length>+" - Use

#to support a comma-separated list, ex."<length>#"

This can be useful for properties that allow multiple definitions, such as background-image.

CSS for "Support multiple values for syntax"

@property --bg-gradient{

syntax: "<image>#";

inherits: false;

initial-value:

repeating-linear-gradient(to right, blue 10px 12px, transparent 12px 22px),

repeating-linear-gradient(to bottom, blue 10px 12px, transparent 12px 22px);

}

.box {

background-image: var(--bg-gradient);

inline-size: 5rem;

aspect-ratio: 1;

border-radius: 4px;

border: 1px solid;

}

Typing for Multi-Part Mixed Values

#Some properties accept mixed types to develop the full value, such as box-shadow which has potential types of inset, a series of <length> values, and a <color>.

Presently, it's not possible to type this in a single @property definition, although you may attempt to try something like "<length>+ <color>". However, this effectively invalidates the @property definition itself.

One alternative is to break up the custom property definitions so that we can allow a series of lengths, and then allow a color. While slightly more cumbersome, this allows us to still get the benefit of typing which relieves the potential errors we covered earlier.

CSS for "Support multi-part mixed values for syntax"

@property --box-shadow-length {

syntax: "<length>+";

inherits: false;

initial-value: 0px 0px 8px 2px;

}

@property --box-shadow-color {

syntax: "<color>";

inherits: false;

initial-value: hsl(0 0% 75%);

}

.box {

box-shadow: var(--box-shadow-length) var(--box-shadow-color);

inline-size: 5rem;

aspect-ratio: 1;

border-radius: 4px;

}

Allowing Any Type

#If you're less concerned about the "type" of a property for something like box-shadow and care more about inheritance or the initial value, you can instead use the universal syntax definition to allow any value. This negates the problem we just mitigated by splitting up the parts.

@property --box-shadow {

syntax: "*";

inherits: false;

initial-value: 0px 0px 8px 2px hsl(0 0% 75%);

}Because the universal syntax accepts any value, an additional "multiplier" is not needed.

Note: The initial-value is still required to be computationally independent as we'll learn about soon under limitations of initial-value.

Join my newsletter for article updates, CSS tips, and front-end resources!

Modifying Inheritance

#A subset of CSS properties are inheritable, such as color. The inherits descriptor for your @property registration allows you to control that behavior for your custom property.

If true, the computed value can look to an ancestor for its value if the property is not explicitly set, and if a value isn't found it will use the initial value.

If false, the computed value will use the initial value if the property is not explicitly set for the element, such as via a class or element rule.

In this demonstration, the --box-bg has been set to inherits: false, and only the outer box has an explicit definition via the applied class. The inner box uses the initial value since inheritance is not allowed.

CSS for "Result of setting inherits: false"

@property --box-bg {

syntax: "<color>";

inherits: false;

initial-value: cyan;

}

.box {

background-color: var(--box-bg);

aspect-ratio: 1;

border-radius: 4px;

padding: 1.5rem;

}

.outer-box {

--box-bg: purple;

}

Valid Use of initial-value

#Unless your syntax is open to any value using the universal syntax definition - "*" - then it is required to set an initial-value to gain the benefits of registering a custom property.

As we've already experienced, use of initial-value was critical in preventing the condition of a completely broken render due to invalid at computed value time. Here are some other benefits of using @property with an initial-value.

When building design systems or UI libraries, it's important to ensure your custom properties are robust and reliable. Providing an initial-value can help prevent a broken experience. Plus, typing properties also meshes nicely with keeping the intent of design tokens which may be expressed as custom properties.

Dynamic computation scenarios such as the use of clamp() have the potential to include an invalid value, whether through an error or from the browser not supporting something within the function. Having a fallback via initial-value ensures that your design remains functional. This fallback behavior is a safeguard for unsupported features as well, though that can be limited by whether the @property rule is supported in the browser being used.

Review additional ways to prevent invalid at computed time that may be more appropriate for your browser support matrix, especially for critical scenarios.

Incorporating @property with initial-value not only enhances the reliability of your CSS but also opens the door to the possibility of better tooling around custom properties. We've previewed the behavior change in browser DevTools, but I'm hopeful for an expansion of tooling including IDE plugins.

The added layer of security from using @property with initial-value helps maintain the intent of your design, even if it isn't perfect for every context.

Limitations of initial-value

#The initial-value is subject to the syntax you define for @property. Beyond that, syntax itself doesn't support every possible value combination, which we previously covered. So, sometimes a little creativity is needed to get the benefit.

Also, initial-value values must be what the spec calls computationally independent. Simplified, this means relative values like em or dynamic functions like clamp() or light-dark() are unfortunately not allowed. However, in these scenarios you can still set an acceptable initial value, and then use a relative or dynamic value when you use the custom property, such as in the :root assignment.

@property --heading-font-size {

syntax: "<length>";

inherits: true;

initial-value: 24px;

}

:root {

--heading-font-size: clamp(1.25rem, 5cqi, 2rem);

}This limitation on relative units or dynamic functions also means other custom properties cannot be used in the initial-value assignment. The previous technique can still be used to mitigate this, where the preferred outcome is composed in the use of the property.

Finally, custom properties registered via @property are still locked into the rules of regular properties, such as that they cannot be used to enable variables in media or container query at-rules. For example, @media (min-width: var(--mq-md)) would still be invalid.

Unsupported initial-value Can Crash the Page

#As of time of writing, using a property or function value that a browser may not support as part of the initial-value definition can cause the entire page to crash!

Fortunately, we can use @supports to test for ultra-modern properties or features before we try to use them as the initial-value.

@supports ([property|feature]) {

/* Feature is supported, use for initial-value */

}

@supports not ([property|feature]) {

/* Feature unsupported, use alternate for initial-value */

}There may still be some surprises where @supports reports true, but testing will reveal a crash or other error (ex. currentColor used with color-mix() in Safari). Be sure to test your solutions cross-browser!

Learn more about ways to test feature support for modern CSS.

Exceptions to Dynamic Limitations

#There are a few conditions which may feel like exceptions to the requirement of "computationally independent" values when used for the initial-value.

First, currentColor is accepted. Unlike a relative value such as em which requires computing font-size of ancestors to compute itself, the value of currentColor can be computed without depending on context.

CSS for "Use of currentColor as initial-value"

@property --border-color {

syntax: "<color>";

inherits: false;

initial-value: currentColor;

}

h2 {

color: blue;

border: 3px solid var(--border-color);

}

My border is set to currentColor

Second, use of "<length-percentage>" enables the use of calc(), which is mentioned in the spec. This allows a calculation that includes what is considered a global, computationally independent unit set even though we often use them for dynamic behavior. That is, the use of viewport units.

For a scenario such as fluid type, this provides a better fallback that keeps the spirit of the intended outcome even though it's overall less ideal for most scenarios.

CSS for "Use of calc() with vi for initial-value"

@property --heading-font-size {

syntax: "<length-percentage>";

inherits: true;

initial-value: calc(18px + 1.5vi);

}

/* In practice, define your ideal sizing function

using `clamp()` via an assignment on `:root` */

h2 {

font-size: var(--heading-font-size);

}

Resize the window to see the fluid behavior

Note: While we typically recommend using rem for font-size definitions, it is considered a relative value and not accepted for use in initial-value, hence the use of px in the calculation.

Consequences of Setting initial-value

#In some scenarios, registering a property without the universal syntax - which means an initial-value is required - has consequences, and limits the property's use.

Some reasons for preferring optional component properties include:

- to use the regular custom property fallback method for your default value, especially if the fallback should be another custom property (ex. a design token)

- an

initial-valuemay result in an unwanted default condition, particularly since it can't include another custom property

A technique I love to use for flexible component styles is including an intentionally undefined custom property so that variants can efficiently be created just by updating the custom property value. Or, purposely using entirely undefined properties to make the base class more inclusive of various scenarios by treating custom properties like a component style API.

For example, if I registered --button-background here as a color, it would never use the correct fallback when my intention was for the default variant to use the fallback.

.button {

/* Use of initial-value would prevent ever using the fallback */

background-color: var(--button-background, var(--color-primary));

/* Intended to be undefined and therefore considered invalid until set */

border-radius: var(--button-border-radius);

}

.button--secondary {

--button-background: var(--color-secondary);

}

.button--rounded {

--button-border-radius: 4px;

}If you also have these scenarios, you may consider using a mixed approach of typing your primitive properties - like --color-primary - but not the component-specific properties.

Considerations For Using @property

#While some of the demos in this article intentionally were set up to have the rendered output use only the initial-value, in practice it would be best to separately define the custom property. Again, this is presently a new feature, so without an additional definition such as in :root you risk not having a value at all if you swap to only relying on initial-value.

You should also be aware that it is possible to register the same property multiple times, and that cascade rules mean the last one will win. This raises the potential for conflicts from accidental overrides. There isn't a way to "scope" the @property rule within a selector.

However, use of cascade layers can modify this behavior since unlayered styles win over layered styles, which includes at-rules. Cascade layers might be a way to manage registration of @property rules if you assign a "properties" layer early on and commit to assigning all registrations to that layer.

Custom properties can also be registered via JavaScript. In fact, this was the original way to do it since this capability was originally coupled with the Houdini APIs. If a property is registered via JS, that definition is likely to win over the one in your stylesheets. That said, if your actual intent is to change a custom property value via JS, learn the more appropriate way to access and set custom properties with JS.

Use of @property has the potential for strengthening container style queries, especially if you are registering properties to act as toggles or enums. In this example, the use of @property helps by typing our theme values, and ensures a fallback of "light".

@property --theme {

syntax: "light | dark";

inherits: true;

initial-value: light;

}

:root {

--theme: dark;

}

@container style(--theme: dark) {

body {

background-color: black;

color: white;

}

}Learn more about this particular idea of using style queries for simplified dark mode.

Although it's a bit outside the scope of this article, another benefit of typing custom properties is that they become animatable. This is because the type turns the value into something CSS knows how to work with, vs. the mysterious open-ended value it would otherwise be. Here's a CodePen example of how registering a color custom property allows animating a range of colors for the background.

Use of @property enables writing safer CSS custom properties, which improves the reliability of your system design, and defends against errors that could impact user experience. A reminder that for now they are a progressive enhancement and should almost always be used in conjunction with an explicit definition of the property.

Be sure to test to ensure your intended outcome of both the allowed syntax, and the result if the initial-value is used in the final render.

This content originally appeared on Modern CSS Solutions and was authored by Stephanie Eckles

Stephanie Eckles | Sciencx (2024-07-19T00:00:00+00:00) Providing Type Definitions for CSS with @property. Retrieved from https://www.scien.cx/2024/07/19/providing-type-definitions-for-css-with-property/

Please log in to upload a file.

There are no updates yet.

Click the Upload button above to add an update.