This content originally appeared on HackerNoon and was authored by Legal PDF: Tech Court Cases

:::tip United States of America v. Google LLC., Court Filing, retrieved on April 30, 2024, is part of HackerNoon’s Legal PDF Series. You can jump to any part of this filing here. This part is 16 of 37.

:::

A. Google Has Monopoly Power In The U.S. General Search Services Market

1. Google’s High And Durable Market Share In General Search Services

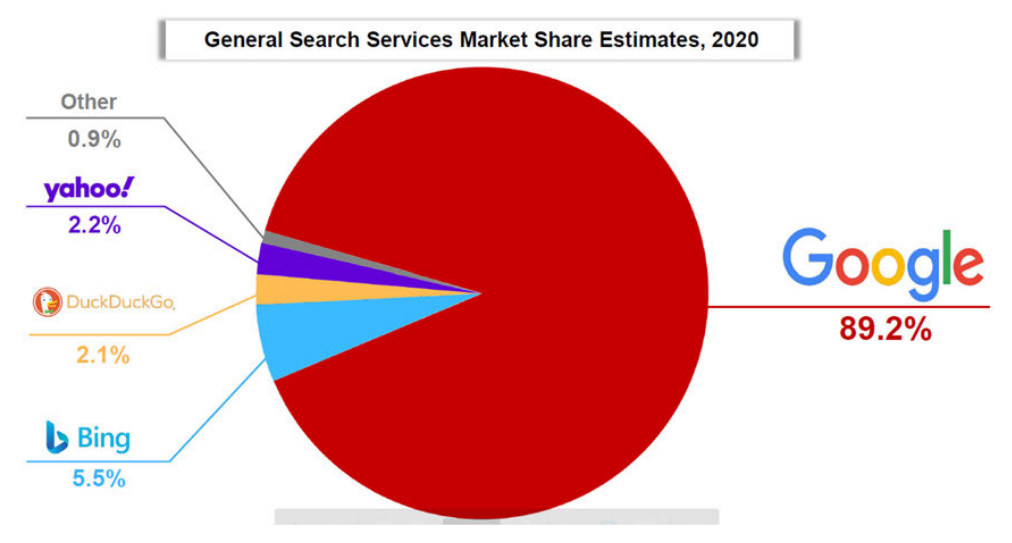

\ 522. In 2020, Google’s market share for general search services in the United States was 89%. Tr. 4761:4–24 (Whinston (Pls. Expert)) (discussing UPXD102 at 47). Google’s three much smaller rivals comprise the remainder of the general search services market in the United States: Microsoft’s Bing (approximately 5.5%), Yahoo (2.2%), and DuckDuckGo (2%)). Tr. 4761:4–24 (Whinston (Pls. Expert)) (discussing UPXD102 at 47); Tr. 8922:3–5 (Israel (Def. Expert)) (accord); Tr. 3488:3–20 (Nadella (Microsoft)) (Bing is a “very, very low share player”); Tr. 2136:6–12 (Weinberg (DuckDuckGo)) (estimating DuckDuckGo’s U.S. market share to be “two and a half percent”). UPXD102 at 47.

\

\ 523. Prof. Whinston prepared these market share calculations relying on ordinary course data from Google and Microsoft and augmenting that with data from StatCounter. Tr. 4761:16–24 (Whinston (Pls. Expert)). StatCounter is an independent third-party source for market share analysis relied on, in the ordinary course, by both Google and other industry participants. Tr. 8684:12–18 (Israel (Def. Expert)) (StatCounter is a source of computing shares for GSEs); Tr. 3832:10–25 (Lowcock (IPG)) (StatCounter is a reliable source for search engine market share analysis); UPX0556 at -027–29 (Google email circulating StatCounter data for GSE market shares).

\ 524. Google does not contest Prof. Whinston’s market share calculations. Dr. Israel conceded that Google’s market share for general search services is around 90%. Tr. 8921:20– 8922:2 (Israel (Def. Expert)).

\ 525. Google’s general search services dominance is even greater on mobile devices, with a U.S. market share of 94.9%. Tr. 4762:19–4763:2 (Whinston (Pls. Expert)) (discussing UPXD102 at 49); UPX0341 at .030 (“Google’s Search share on mobile is high, at 97%, while desktop is lower at 84%”). Google’s advantage in mobile has grown its overall market share. Tr. 5798:17–5799:5 (Whinston (Pls. Expert)) (“it’s important to remember mobile is where the market is growing” and desktop queries are “flat and have been for a long time”); Tr. 3098:6– 3099:3 (Tinter (Microsoft)) (Google’s superior position in mobile and mobile’s growth as a source of user queries has “accelerated [Google’s] market advantage”).

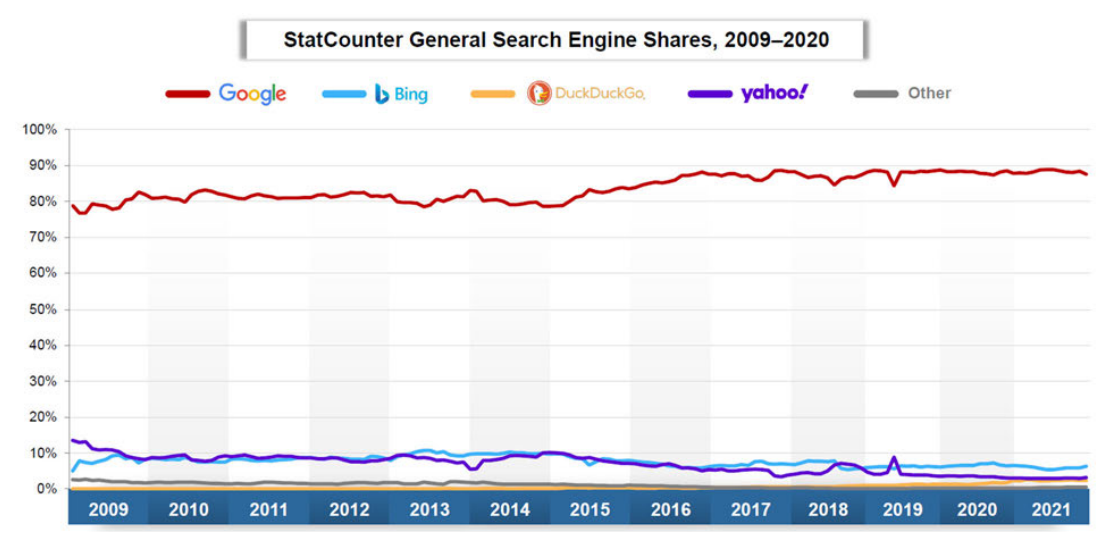

\ 526. Google’s market share in general search services has been durable. Since 2009, Google’s market share in general search services has risen from approximately 80% to nearly 90%. Tr. 4761:25–4762:17 (Whinston (Pls. Expert)) (discussing UPXD102 at 48) (using historical StatCounter data). Prof. Whinston confirmed the reliability of the historical shares from StatCounter by comparing them to historical ordinary course data from Google and Microsoft. Tr. 4761:25–4762:12 (Whinston (Pls. Expert)). Over the past decade, Bing and Yahoo’s market shares have seldomly exceeded 10%. Tr. 4761:25–4762:12 (Whinston (Pls. Expert)) (discussing UPXD102 at 48).

\

\ 527. Google’s ordinary course documents confirm its high market shares for general search services. Between 2010 and 2013, Google monitored its U.S. search engine market share monthly and found that the company held greater than 75% of the market. UPX7001 (FRE 1006 summary of monthly Google internal search share calculation emails); Tr. 203:3–11, 209:3– 210:4 (Varian (Google)) (Google’s monthly share reports are reliable and created by Google statisticians); Des. Tr. 196:20–197:7 (Chu (Google) Dep.) (email reports summarized in UPX7001 were Google statisticians’ best efforts to provide accurate reporting).

\ These monthly market share reports were circulated to Google’s OC, a group of top executives. Tr. 205:18– 206:10 (Varian (Google)) (reviewing UPX0472).

\ 528. Similarly, between 2017 and 2019, Google employees prepared regular “Global Ads Financial Factpacks,” which reported that the company’s general search market share regularly exceed 80% on desktop and reached as high as 98% on mobile. E.g., UPX1075 at -112 (Google had 83% desktop search query share and 97% mobile search query share in 2017Q4); UPX1071 at -209 (Google had 85% desktop query share and 98% mobile query share in 2018Q4); UPX1073 at -221 (Google had 84% desktop query share and 98% mobile query share in 2019Q2)[14]; Tr. 8682:4–8683:20 (Israel (Def. Expert)) (discussing UPX0475).

\ Data prepared for a July 2021 Google Board of Directors meeting reported Google as having 84% and 97% query share in the United States on desktop and mobile, respectively. UPX0909 at -168. Third parties similarly recognize Google’s high market share for general search. UPX0450 at .016 (IPG client presentation “Paid Search 101” showing Google’s market share at 88.43% and explaining in the “Market Share for Search Engines in the USA . . . It Isn’t Even Close.”); Tr. 3833:4–20, 3834:2–18 (Lowcock (IPG)).

\ 529. Recent industry events, such as the release of ChatGPT and OpenAI’s partnership with Microsoft, have not affected Google’s high market share. Tr. 7533:6–7535:19 (Raghavan (Google)) (agreeing that ChatGPT “hasn’t put a dent in Google’s market share”); Tr. 3532:5–19 (Nadella (Microsoft)) (“Q. And one quote I wanted to ask you about, I think at one point you said that ‘ChatGPT or Bing chat is going to make Google dance.’ Do you remember that? A. Yeah. I mean, look, let’s call it exuberance of someone who has like 3 percent share that maybe I’ll have 3.5 percent share”).

\ 530. Output growth can occur even in monopolized markets. Tr. 10456:17–10458:18 (Whinston (Pls. Expert)) (discussing markets where courts concluded that dominant firms held monopoly power even though output was increasing, such as oil production in the Standard Oil decision and PC shipments in Microsoft).

\ 2. Barriers To Entry In General Search Services Are High

\ a) Complexity And Cost Of Constructing A General Search Engine Are Significant Entry Barriers

\ 531. Building a GSE requires crawling the web, constructing an index, developing a search function capable of retrieving and ranking the websites, and displaying results through a SERP accessible to consumers. Supra ¶¶ 57–72 (§ III.A). A GSE must search and present responses to queries from the trillions of documents on the internet. Tr. 6302:14–20 (Nayak (Google)) (discussing DXD-17); Tr. 3699:17–3701:12 (Ramaswamy (Neeva)).

\ 532. To be viable, a GSE must first crawl a vast amount of the web and log information on websites to build an index. Supra ¶ 67. Web crawling of that magnitude requires a “huge set of computers.” UPX8052 at .002.

\ 533. Crawling a webpage imposes financial and resource costs on the webpage owner. Tr. 6309:4–6310:5 (Nayak (Google)) (crawling a webpage uses that page’s resources). Accordingly, GSEs often need permission to crawl webpages from page owners, some of whom only give permission to large GSEs. Tr. 2656:19–2658:24 (Parakhin (Microsoft)) (webmasters often give priority for crawling to search engines with greater scale); UPX8052 at .002 (some website owners prohibit crawling on their webpages).

\ Webpage owners will often allow only Google or the most popular search engines to crawl their page and disallow crawling by everyone else—even established competitors. Tr. 2656:19–2657:24 (Parakhin (Microsoft)) (“It is fairly standard practice often to go and allow [sic] most popular search engines, and just disallow everybody else”); Tr. 2666:21–2667:12 (Parakhin (Microsoft)) (a large e-commerce site in Turkey blocked crawling by all GSEs except Google, which made Yandex’s results “very uncompetitive”).

\ 534. Indexing is the process of converting the web crawl into a database organized to allow the GSE to efficiently return responses to user queries. Supra ¶ 68.Because of the internet’s massive volume, determining how to index it is “a real challenge.” Tr. 6302:21–6303:1 (Nayak (Google)). Most good engineers “would basically give up on” crawling and indexing the web “before they start, because it is a Herculean problem.” Tr. 3699:13–3701:12 (Ramaswamy (Neeva)).

\ 535. The sheer size of the internet and the amount of spam and poor-quality content means that a GSE cannot store all webpages in an index; a viable GSE must instead understand what to index and how to organize the index’s contents. Tr. 6303:2–6304:21, 6309:4–6310:5 (Nayak (Google)). A web index must be comprehensive enough to answer user queries, even uncommon queries in the long tail. Tr. 6303:2–25, 6308:12–6309:1 (Nayak (Google)); infra ¶¶ 985–1006 (§ VIII.A.2.a.i–ii).

\ The index must also remain current, requiring crawlers to work constantly. Tr. 6304:1–21 (Nayak (Google)) (“[I]f you want to search the web effectively, you need to keep your index up-to-date.”); Tr. 2251:19–23 (Giannandrea (Apple)). infra ¶¶ 1006– 1010 (§ VIII.A.2.a.iii).

\ 536. Retrieval and ranking—the final “crucial” steps for operating a GSE—are the “hardest problem[s] in search.” Tr. 2253:15–2255:3 (Giannandrea (Apple)); Tr. 6330:25– 6332:18 (Nayak (Google)); supra ¶¶ 70–71. Because as many as 10 million results could match a query, a search engine must quickly rank webpages that are most responsive. Tr. 6330:25– 6332:18, 6398:25–6399:9 (Nayak (Google)); Tr. 2253:15–25, 2254:10–14 (Giannandrea (Apple)).

\ 537. In addition to the technical complexity of these tasks, building, maintaining, and growing the component parts of a GSE—the crawler, the indexer, and the retrieval and ranking mechanisms—requires significant capital investment; this too acts as an entry barrier. Tr. 4764:1–4765:6, 4765:12–25 (Whinston (Pls. Expert)); Tr. 2267:17–2268:7 (Giannandrea (Apple)) (building a competitive GSE is “very expensive.”); Tr. 6304:22–6305:3 (Nayak (Google)) (indexing alone requires “a very significant cost” for machines, bandwidth, and data storage).

\ 538. The “depth of R&D needed” to build and maintain a GSE is an entry barrier that has resulted in “few serious contenders” in general web search. UPX0266 at -983.

\ Microsoft has invested approximately $100 billion in Bing during the past two decades. Tr. 3510:16–23 (Nadella (Microsoft)); Tr. 2682:10–15 (Parakhin (Microsoft)) (“Bing made tremendous efforts over the years. Like empirically speaking, no other company could or did afford the amount of investment that was needed to stay viable at the level of scale that Bing had.”). As estimated by Google’s former head of search, Mr. Giannandrea, “a world class search engine is at least a $2– 4B/year investment and that is before you build a search ads business to pay for it.”

\ UPX0266 at -986; Tr. 2295:3–16 (Giannandrea (Apple)) (Apple’s finance team concluded that an Apple search product would cost $6 billion in annual serving and operating costs.); UPX0460 at -177; DX0374 at -301 (Mr. Giannandrea advised Apple CEO Tim Cook against acquiring Bing because it would be a “multi billion dollar investment.”). Google estimated that it would cost Apple $10 billion annually to operate its own GSE. Tr. 1650:5–1653:11 (Roszak (Google)) (discussing UPX0002 at -392–93).

\ 539. Venture capital funding is also difficult to obtain for general search. UPX0240 at -507 (“[T]he reason a better search engine has not appeared is that it’s not a VC fundable proposition even though it’s a lucrative business.”); Tr. 5848:15–5949:1 (Whinston (Pls. Expert)) (“[Y]ou see this sometimes in references like, oh, search is a place that venture capital does not go”).

\ 540. Overcoming the cost and complexity of building a GSE is necessary but not sufficient to ensure successful entry into the general search services market, as evidenced by the recent exit of Neeva. Dr. Ramaswamy, who had worked at Google for fifteen years and risen to lead the company’s search infrastructure team, started Neeva with two other former Google employees and was backed by two substantial funding rounds. Tr. 3667:3–3668:15, 3669:15– 3670:5, 3672:6–13, 3674:16–3677:10 (Ramaswamy (Neeva)).

\ Neeva sought to differentiate itself by being ads-free, privacy-focused, and offering a more personalized experience using generative AI. Tr. 3718:25–3719:16 (Ramaswamy (Neeva)); UPX0940 at -490–91. Despite raising a substantial amount of money, having engineering prowess, and peaking at several million monthly active users, Neeva was unable to compete in the general search services market. Tr. 3674:16–3675:6, 3699:13–3701:12, 3710:15–3712:20, 3734:12–3735:10 (Ramaswamy (Neeva)). As Dr. Ramaswamy explained, “if a well-funded and exceptionally talented team like Neeva could not even be a provider on most of the browsers, I don’t see that as the market working.” Tr. 3723:22–3724:23 (Ramaswamy (Neeva)).

\ b) Acquiring Scale Necessary Is A Significant Entry Barrier

\ 541. The need to acquire scale is a significant barrier to entry. Tr. 4766:10–15, 5781:8– 5782:8, 5783:15–20 (Whinston (Pls. Expert)). Scale is vital for improving search and ad quality. Supra ¶¶ 978–1066 (§ VIII.A). Increased search quality attracts additional users, and advertisers follow users. Infra ¶ 587. Additional users and advertisers result in increased revenue, which increases the resources available for distribution. Infra ¶¶ 798–817, 1093–1101. That is, these additional resources lead to additional scale and search quality, again, attracting more users and fueling a cycle of improvement. Supra ¶ 193.

\ 542. Without access to scale, rivals’ ability to compete is directly and indirectly weakened. Tr. 5781:8–5782:8, 5783:15–20 (Whinston (Pls. Expert)) (“If rivals have reduced scale, that can directly reduce the quality of their search services and their ad as well. So they— basically, reduced scale directly weakens rivals as competitors.”). The need to acquire scale to build a quality search engine is a significant barrier to entry. Id. 4766:10–15, 5781:8–5782:8, 5783:15–20.

\ c) Brand Recognition And Consumer Loyalty Are Significant Entry Barriers

\ 543. Google’s strong brand recognition and consumer loyalty create an entry barrier. Des. Tr. 91:18–92:8 (van der Kooi (Microsoft) Dep.) (“[I]t was very hard to market against something that is a brand name already out there and to then drive usage from TV commercials.”). To “Google” is a verb. Tr. 3547:19–22 (Nadella (Microsoft)); Tr. 622:25–624:4 (Rangel (Pls. Expert)); Tr. 4769:10–16 (Whinston (Pls. Expert)) (“Being a verb helps”). The Google brand is so entrenched that users “generally blame themselves and try and reformulate their query” when they are dissatisfied with search results. Tr. 3741:3–3742:16 (Ramaswamy (Neeva)); Tr. 3491:23–3493:8 (Nadella (Microsoft)) (“[W]ith search in particular . . . once you have dominant share, users are just most familiar with your user experience, and change is hard.”). This affords Google stickiness and latitude among users that Google’s competitors do not enjoy. Tr. 3741:3–3742:16 (Ramaswamy (Neeva)).

\ 544. When Google implemented a choice screen on Android devices in Europe, Google’s brand recognition helped minimize defection. Tr. 622:25–625:14 (Rangel (Pls. Expert)); UPX1103 at -775 (“The reason the financial impact is not shifting based on the placement of Google in the choice screen is because the assumptions we used in the model are based on brand recognition (using queries as a proxy)-considering this is what the assumption is meant to capture, the position wouldn't matter as much as the recognition would.”).

\ 545. Google's "very strong brand recognition” is “something that a new entrant would need to overcome” and is a significant entry barrier. Tr. 4766:2–9 (Whinston (Pls. Expert)).

\ d) Google’s Control Of Search Access Points Through Its Exclusionary Contracts Is A Significant Entry Barrier

\ 546. Google's search distribution contracts with Apple, Mozilla, and Android OEMs and carriers are a significant barrier to entry.

\ 547. Default placement in a search access point is by far the most effective method of driving traffic to a GSE and accounts for the overwhelming majority of a GSE's search queries. Infra¶883. Most search traffic reaches a GSE through defaults; organic queries account for only a small percentage of traffic. Infra ¶ 883. Other distribution methods such as marketing and downloads in app stores are ineffective compared to default distribution. Infra ¶¶880-881. Google's agreements raise users switching costs, infra ¶¶ 891–913 (§ VI.D.3.C), and make entry and expansion more difficult by ensuring that rivals are excluded from search access points, infra ¶¶ 546-549 (§ V.A.2.d).

\ 548. Google's Android partners told Dr. Ramaswamy that Google's contract made it "very, very hard" for them to offer Neeva as an option for the search engine default on devices they controlled. Tr. 3691:18–3692:12 (Ramaswamy (Neeva)); UPX0957 at -881 (Distribution partnerships with OEMs have “Search Defaults” locked-in with Google); UPX0958 (partners’ spreadsheet detailing Neeva’s unsuccessful efforts to secure distribution with Android carriers and OEMs). The absence of Neeva as an option for search defaults on major browsers and operating systems was one reason Neeva exited the general search market. Tr. 3690:5–3691:9, 3699:13–3701:12 (Ramaswamy (Neeva)).

\ 549. Google’s contracts with Apple, Mozilla, and Android OEMs and carriers make entry more difficult by ensuring that rivals are excluded from search access points. Tr. 4767:7– 4767:15 (Whinston (Pls. Expert)) (discussing UPXD102 at 51). Forcing rivals to less effective distribution channels raises the cost of entry and expansion. Id.

\ e) Google’s Control Of The Default On Chrome Is A Significant Entry Barrier

\ 550. Almost one-fifth of all general search queries in the United States go through the default on user-downloaded versions of Chrome (e.g., Chrome on Windows and Apple devices). Infra ¶ 968. Google, as the Chrome’s owner, always sets itself as Chrome’s default search engine. Infra ¶ 969. Google’s ownership of Chrome and control of the default on Chrome is thus a barrier to entering the general search services market because rivals have no opportunity to attain default distribution for almost one in five U.S. general search queries. Tr. 4766:24–4767:5 (Whinston (Pls. Expert)) (discussing UPXD102 at 51).

\ 551. [INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK]

\ 552. [INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK]

\ 553. [INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK]

\ 554. [INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK]

\ 555. [INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK]

\ 556. [INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK]

\ f) Syndicated Entry Does Not Offer A Meaningful Workaround To Entry Barriers

\ 557. Search syndication, supra ¶ 74–76 (§ III.B.1.a), does not offer a meaningful workaround to entry barriers because options are limited and there is no opportunity to innovate. In 2019, when considering syndication partners, DuckDuckGo was limited to Google, Bing, and DuckDuckGo’s then-partner Yahoo, which itself syndicates from Bing. Tr. 2061:18–2062:9 (Weinberg (DuckDuckGo)). [redacted] DX1037 at -439–40.

\ 558. Neeva built its own search technology in part because it “felt that [it] could not innovate as much as [it] wanted to on top of” Bing’s syndicated feed. Tr. 3739:20–3740:7 (Ramaswamy (Neeva)).

\ 3. Google’s Quality And Monetization Advantages Are Evidence Of And Contribute To Its Monopoly Power In The General Search Services Market

\ a) Google’s Quality Advantage Is Evidence Of And Contributes To Its Monopoly Power

\ 559. Google’s search quality advantage over rivals is evidence of and contributes to its monopoly power. Tr. 4767:17–4769:13 (Whinston (Pls. Expert)). One way Google measures its search quality against its competitors is by usings a pool of paid human raters to evaluate search results. UPX0872 at -848; Tr. 1779:21–1780:1 (Lehman (Google)); Tr. 8099:14–25 (Gomes (Google)). To do this, Google will “sample user queries, send these queries as well as Google or Bing results to [Google] raters and ask them to rate how good a result is for a query.” UPX0872 at -848; Tr. 6323:19–6324:24 (Nayak (Google)).

\ Each of the queries evaluated by a human rater will individually be given an “Information Satisfaction,” or IS, score. Tr. 1779:21–1780:1, 1813:6–1814:4 (Lehman (Google)). Individual IS scores are then aggregated over all the queries in the experiment and Google rolls them up into a score between 1 to 100. Tr. 1813:6–1814:4 (Lehman (Google)) (IS scale is 0 to 100); UPX0872 at -848 (Google, “then . . . roll[s] up all these assessments into a metric for tracking and experimentation.”).

\ To conceptualize what onepoint means on this scale, Google notes that removing Wikipedia—“a really important source on the web”—results in an IS loss of roughly a half point. Tr. 6323:6–18 (Nayak (Google)) (“So that gives you a sense for what a point of IS is. A half point is a pretty significant difference if it represents the whole Wikipedia wealth of information there.

\ So that’s how we’ve been thinking about it.”). On an annual basis, Google usually attempts to improve its quality by 1 IS point. Tr. 1812:12–20 (Lehman (Google)) (one-point IS gain is a good yearly goal); UPX0217 at -792.

\ 560. In 2020, on mobile Google outperformed Bing, its next closest competitor, by approximately about four IS4@5 points. UPX0268 at -122; Tr. 1779:1–1780:1 (Lehman (Google)) (IS4 indicates the fourth version of the IS metric.); id. 1814:11–1814:14 (“[T]he ‘at’ usually refers to the number of results that are being evaluated.”

\ For example, IS4@5 means that human raters evaluated the top five results.). This IS score gap represents a “fairly meaningful difference in quality” of at least 8 Wikipedia points. Tr. 6323:6–18, 6369:6–12 (Nayak (Google)).

\ Google has maintained its quality lead for a prolonged period. Tr. 4768:5–4769:9 (Whinston (Pls. Expert)) (referencing UPXD102 at 55, “[b]etween 2015 and 2021, the difference in the US between Google’s and Bing’s IS scores ranged from ~3 to 8 points”); Tr. 8100:19–21 (Gomes (Google)) (agreeing that during his time heading search, the IS4 rankings between Google and Bing, Google always had a higher ranking). Google also maintains a quality lead in important segments like tail queries which make up a large portion of the overall query stream. Infra ¶¶ 981–982, 990 (empirical analysis showing Google’s IS score advantage particularly in tail queries), ¶¶ 991, 995–997, 1000–1001.

\ Google’s quality advantage contributes to and is evidence of its monopoly because it allows Google to retain users by simply being “good enough” (because “good enough” is still better than rivals) rather than improving the quality of its product as it would in a competitive market. Tr. 4767:16–4768:4 (Whinston (Pls. Expert)).

\ b) Google’s Monetization Advantage Is Evidence Of And Contribute To Its Monopoly Power

\ 561. Google has had, and maintains, a monetization advantage over its rivals— particularly Bing and particularly on mobile. UPX0014 at -984 (discussing Bing’s “RPM gap relative to Google” and “significant headroom for RPM growth”); Tr. 4769:17–4770:22 (Whinston (Pls. Expert)) (referencing UPXD102 at 55–56, illustrating the RPM gap between Google and Bing over time). In fact, the RPM gap between Google and Bing on mobile has grown over time as Bing has continued to lack access to mobile defaults. Id. Illustrated differently, Google had a massive [redacted]% profit margin on Search Ads in 2022, which was consistent with its profit margins for the preceding decade. Infra ¶ 598.

\ 562. As Microsoft explained to Apple in 2016, Microsoft’s search and ads syndication deal with Yahoo in 2010 demonstrated that scale was a critical reason for the RPM gap and “adding volume to [Bing’s] search ads marketplace from Apple devices will increase revenue per search.” UPX0246 at -255; id. at -260–61 (explaining the direct scale impact on RPM as a result of Microsoft’s 2010 partnership with Yahoo); infra ¶¶ 1062–1066, 1078 (Microsoft discussions with Apple about benefits of attaining query volume from Apple devices).

\ In general search services, unlike in many other product markets where dominant firms may have cost advantages, this significant negative marginal cost advantage for Google over its rivals, particularly in mobile, is evidence of and contributes to Google’s market power. Tr. 4767:17–4770:22 (Whinston (Pls. Expert)).

\ For example, because of Google’s monetization advantage, Microsoft’s 2016 offer of 90% revenue share to Apple was “not really interesting” compared to Google’s offer of just 40% revenue share. Tr. 2510:19–2511:11 (Cue (Apple)); infra ¶¶ 1263–1272.

\ Google’s monopoly is insulated from meaningful competition when its rivals must offer all, or almost all, of their Search Ads revenue to win default distribution.

\ 4. Direct Evidence Of Google’s Monopoly Power In The General Search Services Market

\ a) Google Extracts Private User Data Beyond What It Knows Users Prefer

\ 563. Google’s ability to ignore competition in privacy and maintain policies and practices that are contrary to consumer desires for increased privacy in search is direct evidence of its monopoly power. Tr. 5854:11–5856:14 (Whinston (Pls. Expert)) (Google’s monopoly enables it to offer users less privacy than it would in a competitive market).

\ 564. Privacy is an important dimension of competition for GSEs. Infra ¶¶ 1137–1139. Senior Google executives, however, have refused to adopt additional privacy improvements because they do not perceive a risk of losing users to competing GSEs due to privacy considerations; rather, Google acts only if a privacy deficiency will actually lead to fewer queries. Infra ¶¶ 1143–1146. Google would “never” choose a privacy default “based purely on what users tell us in survey research.” Tr. 9057:9–9058:2 (Fitzpatrick (Google)).

\ Rather than compete on privacy, Google accepts that there are “huge gaps” between the privacy protections that it offers compared to those of rivals like DuckDuckGo. UPX0811 at -420, -423, -445; Tr. 2063:24–2064:4 (Weinberg (DuckDuckGo)) (DuckDuckGo collects only anonymized search data and deletes the data).

\ 565. Instead of improving privacy in response to competition, Google maintains privacy policies and practices that dissatisfy its users. Tr. 7453:12–7454:4 (Raghavan (Google)) (Google performed poorly on data privacy and data security in a user survey, which were the most important attributes for user trust); DX0183 at .015 (“Google had weak performance scores on top drivers across all 4 markets”; showing Google’s U.S. performance scores of 24% for both “[r]espects my privacy” and “[k]eeps my personal data secure”); id. at .004 (“Security and Privacy are most important drivers of trust in Search.

\ However, we perform poorly on these four attributes across all 4 markets”); UPX1069 at -661–62 (privacy concerns were the biggest contributor to declining user trust in the Google brand).

\ 566. By default, Google retains 18 months of user search history and web activity; Google allows users to change this setting, but only offers 3 months or 36 months of data retention as alternatives. Infra ¶¶ 1152–1153. Google set its default data collection at 18 months for no reason other than that 13 months “just felt like a really weird number.” Tr. 9012:21– 9013:18 (Fitzpatrick (Google)). Similarly, Google considered implementing a “slider” that would allow users to select any duration option within a given range for their personal auto-delete, datastoring preference but decided not to. Id. 9012:4–19, 9051:6–9054:16.

\ Instead, if users wish to customize their auto-deletion, they must manually delete their search history. Id. 9012:4–19, 9013:19–9014:19. Additionally, changing the 18-month default (to either 3 months or 36 months) requires as many as 10 clicks and involves “considerable choice friction.” Infra ¶¶ 1153, 1158.

\ 567. Google sets the auto-delete default to 18 months despite its own survey showing that 74% of users would prefer that Google store their data for one year or less. Infra ¶ 1153.

\ b) Google Captures Significant Surplus From Its Distribution Deals

\ 568. Google’s ability to capture significant surplus from its search distribution deals is evidence of monopoly power in general search services. Tr. 4773:23–4775:13 (Whinston (Pls. Expert)). As Google’s chief economist Dr. Varian agreed, large profits are an indicator of monopoly power. Tr. 414:8–10 (Varian (Google)).

\ 569. In Google’s search distribution agreements, the remaining sum after Google pays the net revenue share is Google’s profit. Tr. 4773:23–4774:25 (Whinston (Pls. Expert)). Google’s profit margin for its ISA with Apple is 64%. JX0033 at -797 (§ 4) (Apple ISA (2016 amend.)). Although this revenue share costs Google billions of dollars, the deal is nevertheless “profitable” for Google because it generates “more billions and billions in revenue.” Tr. 7780:16–7781:24 (Pichai (Google)). The magnitude of Google’s profit is a sign of Google’s large market power. Tr. 4773:23–4775:13 (Whinston (Pls. Expert)); id. 4775:15–4777:5 (“[W]hen firms have a really, really big advantage, that is very likely to coincide with market power.”).

\ 570. Google has been “very insulated” from competitive responsiveness during its negotiations with Apple. Id. 4775:15–4777:5. In a competitive market, Apple would be able to play Google against GSE rivals and capture more of the profits by negotiating a higher revenue share. Id. 4773:23–4775:13 (“[I]f [Google] had equally capable rivals, it wouldn’t be able to make that amount of money.

\ Apple would play them off against each other. So when you see that level of profit, it’s telling you that there’s a really big gap and they have a lot of market power.”); id. 10460:22–10462:23 (“[I]f Google faced rivals that were kind of on par with it, Apple would be able to play them off each other and make almost all the profit in this deal.”).

\ As Adrian Perica, Apple’s head of corporate development, explained, a more competitive Bing— perhaps bolstered by additional traffic from Apple users—would “create incremental negotiating leverage to keep the take rate high from Google, and further our optionality to replace Google down the line.” UPX0240 at -506. Instead, Mr. Pichai admitted that Google “didn’t pay the [revenue] share Apple wanted” because Google knew that it was Apple’s “only viable option.” Tr. 7772:12–7773:10 (Pichai (Google)); Tr. 2464:8–2465:7 (Cue (Apple)) (Apple has no “valid alternative” to Google for Safari’s default); Tr. 10460:22–10462:23 (Whinston (Pls. Expert)) (Pichai’s testimony demonstrates Google’s monopoly power); Tr. 9783:21–9787:1 (Murphy (Def. Expert)) (Google had “a lot of headroom” in Apple revenue share negotiations).

\ c) Google Does Not Invest In Quality Improvements

\ 571. Google’s failure to invest in quality improvements is direct evidence of its monopoly power in general search services. Google “does not . . . consider whether users will go to other specific search providers (general or otherwise) if it introduces a change to its Search product.” UPX6019 at -365–66 (written 30(b)(6) response).

\ 572. When Google has run quality degradation experiments, it has found user substitution was very limited, meaning that there was little cost to Google and reduced incentives to invest in quality improvements. UPX1082 at -294; Tr. 4770:23–4772:24 (Whinston (Pls. Expert)) (explaining UPX1082 at -294). Google has underinvested in search despite significant overall growth in search queries. Despite seeing a 45% increase in total queries between 2014 and 2017, Google decreased spending on search machines during that period. UPX0752 at -017.

\ This “under-invest[ment]” led to corresponding decreases in search quality, including a smaller index, higher latency, and serving errors. Des. Tr. 192:1–196:19 (Porat (Google) Dep.) (discussing UPX0752 at -017); UPX0752 at -017; UPX0223 at -122 (graph of Google’s latency increase); Tr. 7443:9–7445:17, 7450:2–7451:4 (Raghavan (Google)) (rejected a proposed investment in more data centers to reduce latency). Google’s crawl has also not kept pace with the size of the web: in 2017, Google’s index fell by 40% even as queries on its search engine have increased. UPX0722 at -308; UPX0249 at -547 (depicting Google’s query growth and index decline on a chart).

\ 573. Google’s “R&D” intensity has not been high relative to other firms. Tr. 5857:5– 5858:21. (Whinston (Pls. Expert)) (discussing UPXD104 at 79).

\ 574. Google’s ability to avoid investing in quality improvements at the rate it would in a competitive market is a sign of monopoly power in the general search services market, where there is no monetary price for users. Id. 10476:24–10477:12; UPX0891 at -884 (“Because Search is organizationally firewalled from Ads, revenue is not tracked directly. Value is therefore typically expressed in terms of improvements in well-understood metrics” such as rater-based Information Satisfaction, or IS, scores and live experiment metrics.).

\ \

:::tip Continue Reading Here.

:::

:::info About HackerNoon Legal PDF Series: We bring you the most important technical and insightful public domain court case filings.

\ This court case retrieved on April 30, 2024, storage.courtlistener is part of the public domain. The court-created documents are works of the federal government, and under copyright law, are automatically placed in the public domain and may be shared without legal restriction.

:::

[14] Additional Financial Factpacks: UPX2007 at -659 (2017Q1); UPX2008 at -640 (2017Q2); UPX2009 at -265 (2017Q3); UPX1076 at -651 (2018Q1); UPX0475 at -744 (2018Q2); UPX1074 at -166 (2018Q3); UPX1072 at -742 (2019Q1); UPX0476 at -668 (2019Q3).

This content originally appeared on HackerNoon and was authored by Legal PDF: Tech Court Cases

Legal PDF: Tech Court Cases | Sciencx (2024-08-10T17:30:16+00:00) The U.S. Government: Google Has Monopoly Power In The U.S. General Search Services Market. Retrieved from https://www.scien.cx/2024/08/10/the-u-s-government-google-has-monopoly-power-in-the-u-s-general-search-services-market-2/

Please log in to upload a file.

There are no updates yet.

Click the Upload button above to add an update.