This content originally appeared on HackerNoon and was authored by Diurnal

Table of Links

Introduction

1.1. Io as the main source of mass for the magnetosphere

1.2. Stability and variability of the Io torus system

Review of the relevant components of the Io-Jupiter system

2.1. Volcanic activity: hot spots and plumes

2.3 Exosphere and atmospheric escape

2.5. Neutrals from Io in Jupiter’s magnetosphere

2.6. Plasma torus and sheet, energetic particles

-

3.2 Canonical number for mass supply

3.3 Transient events in the plasma torus, neutral clouds and nebula, and aurora

3.4 Gaps in understanding, contradictions, and inconsistencies

Future observations and methods and 4.1 Spacecraft measurements

\ Appendix, Acknowledgements, and References

2.6. Plasma torus and sheet, energetic particles

Since the discovery of sulfur emissions (Kupo et al., 1976) observations of the plasma torus have been made by ground- and space-based telescopes, and in situ and remote spacecraft measurements. These observations show that most of the time the Io plasma torus is overall stable over weeks or months, although the amount of material supplied directly or indirectly from Io to the magnetosphere likely varies on different time scales. Significant transient changes in the torus on time scales of days up to 2 months were inferred from different observations. These changes were suggested to be triggered by changes in mass supply from Io. To understand the feedback mechanisms that generally stabilize the structure and density of the Io plasma torus but sometimes allow transient changes, we need to understand the mass and energy balance in the Io plasma torus and how the system responds to changes in the source of material.

\ Reviews of the plasma torus can be found in Bagenal and Dols (2020), Thomas et al. (2004) or for a past-Voyager perspective in Strobel (1989).

2.6.1. General description of the Io plasma torus and energetic particles

\ The transport of plasma in the warm torus outward is due to the centrifugal-force-driven instability (Siscoe and Summers, 1981). As plasma transports slowly outward, the azimuthal plasma flow is accelerated by transporting the planetary angular momentum through a magnetosphere-ionosphere coupling current system (Cowley and Bunce, 2001; Hill, 1979). The Io-genic plasma is heated in the magnetosphere, and the energetic sulfur and oxygen ions become primary contributors to the plasma pressure in the plasma disk (Mauk et al., 2004).

\ Plasma in the torus is generated at Io’s orbital distance through ionization of the neutral clouds (Section 2.5) and by ionization and pick-up from Io’s atmosphere (to a smaller extent, Section 2.4). As the plasma from the torus is transported outward and the energetic ions are accumulated in the plasma disk, the plasma disk becomes unstable. The plasma in the disk is finally released from the magnetosphere toward the tail region through reconnection (e.g., Kivelson and Southwood 2005, Hill 2006). The bulk convection of this material through the magnetosphere produces a dawn-dusk electric field (Ip & Goertz 1983, Barbosa and Kivelson 1983). This offsets the entire plasma torus dawnward resulting in adiabatic heating of plasma on the dusk side. The measured UV brightness asymmetry (Murakami et al., 2016) and ribbon positions (Schmidt et al., 2018), agree on a mean field strength of 3.8 mV/m, with a spread of 1-9 mV/m that is dependent on the solar wind and plasma convection rates. The plasmoid ejection via the Vasyliunas type reconnection (Vasyliunas, 1983) is thought to be the predominant process to release mass from Jupiter’s magnetosphere (McComas et al., 2007). However, the communication of plasmoid losses back to the torus at the Alfvén speed is comparable to the Jovian rotation period, and so it is challenging to connect events in the torus and events in the magnetotail unambiguously.

2.6.2 Stability of the Io plasma torus

The stability of the Io plasma torus in response to the variable input has been discussed based on either the regulation of the escape of material from Io (“supply-limited”) or the regulation of the loss from the plasma torus (“loss-limited”) (Brown and Bouchez, 1997). The system is supply-limited if an increase in plasma density in the torus causes a decrease in the escape of material from Io's atmosphere. For example, an increase in plasma precipitation into Io's atmosphere increases the ionospheric conductivity, which causes the plasma flow to deflect around Io, reducing plasma precipitation and subsequent atmospheric escape. The system becomes loss-limited if the increase in plasma supply to the torus leads to an increase in plasma loss from the torus. The centrifugal-force-driven interchange instability can become unstable if the outward gradient of plasma mass density increases due to an increase in the plasma source from Io, which is feasible with the loss-limited process. A challenge for this interchange instability might be due to heavily-loaded flux tube fingers with very small longitudinal width and thus difficult to detect even with orbiting spacecraft (Yang et al., 1994).

\ According to the Cassini and Hisaki observations described in Section 2.6.3, the loss rate from the plasma torus increases as the neutral source rate in the torus increases, which agrees with the loss-limited scenario. Also, some of the key features (e.g., changes in the radial gradient of plasma density) have been observed by the spatially resolved observations of the plasma torus (Hikida et al., 2020; Tsuchiya et al., 2018; Yoshioka et al., 2018). On the other hand, to investigate the supply-limited scenario, it is necessary to understand the evolution of Io’s atmosphere and ionosphere and the associated changes in satellite-plasma interactions and mass exchange (Section 2.4).

2.6.3 Transient changes in the torus

In the last two decades, clear and significant changes in the Io plasma torus on timescales of weeks to months have been detected twice from ultraviolet (UV) observations made by Cassini/UVIS (UV Imaging Spectrograph) and the Hisaki spectroscope in 2001 and 2015, respectively. Studying these events allowed significant updates on how the system responds to changes.

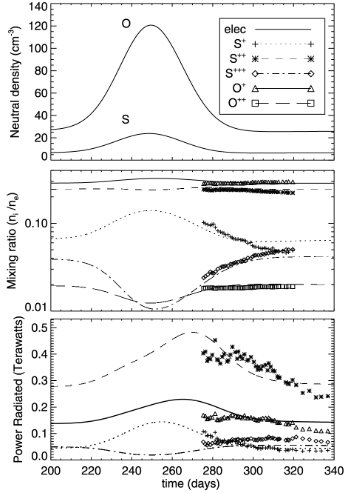

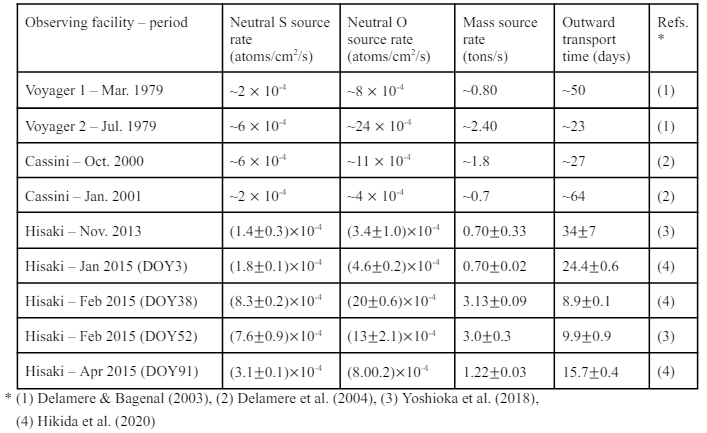

\ 2000/2001 event. Observations of torus emissions made during the Cassini flyby of Jupiter (October 2000 to March 2001) showed the short-term variations of the torus over a ~4-month period. The measurements of the emissions of all major ionized species allowed estimation of the density, composition, and temperatures in the plasma torus (Steffl et al., 2004a; 2004b). Delamere et al. (2004) modeled the changes seen in the Cassini data (Figure 17), deriving that the neutral source rate for torus supply changed from >1.8 tons/s to 0.7 tons/s, i.e., by a factor of >2.5. The putatively increased dust rate as diagnostic for an enhanced volcanic activity before the Cassini UVIS measurements as invoked by Delamere et al. (2004) is, however, not confirmed and questionable (see Section 2.8).

\

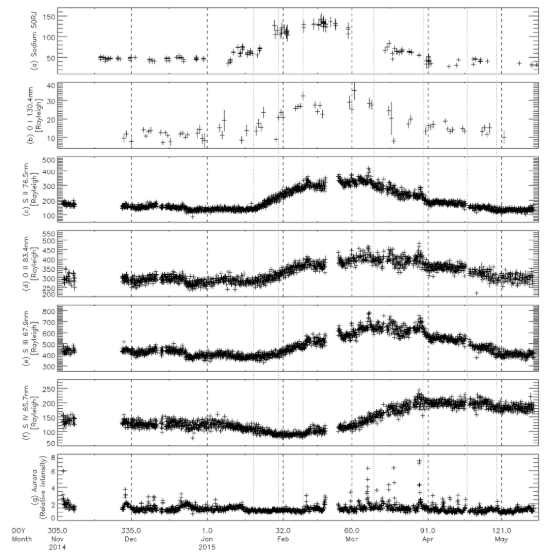

\ 2015 event. The Hisaki satellite has been conducting long-term monitoring of Io plasma torus since December 2013 and has captured the response of the magnetosphere to the increase in neutrals from Io in early 2015 (Kimura et al., 2018; Koga et al., 2018a; Tao et al., 2018; Tsuchiya et al., 2018; Yoshikawa et al., 2017; Yoshioka et al., 2018). Ground-based sodium observations showed an increase in brightness during a period from mid-January to March 2015 (Yoneda et al., 2015). Hisaki identified not only an increase in ion emissions but an increase in neutral oxygen atom emissions around Io by a factor of 2.5 which is correlated well with the increase in sodium emissions for this event (Koga et al., 2018a). The changes in neutral gas emissions and subsequent changes in singly- and multiply-ionized species suggest that the supply of neutral species and the subsequent plasma supply to the magnetosphere increased over a period of a few weeks (Figure 18). There were suggestions that specific detected hot spots (e.g., an outburst at Kurdalagon) triggered this event, but the relationship between hotspots and changes in the neutral cloud and torus is completely unclear (Section 2.1) and connections made were purely based on temporal coincidence of hot spot detections with onset of the gas emission increase. During the other observing seasons of the Hisaki satellite, a relatively stable torus with only smaller variations or long-term trends were measured (Tsuchiya et al., 2019; Roth et al., 2020).

\ Voyager event 1979. Delamere and Bagenal (2003) found that the torus underwent a change in a re-analysis of UV observations from the Voyager 1 flyby in March 1979 and later Voyager 2 flyby in July 1979. The change in torus emissions was on a similar scale than that found in Cassini data and the authors derived a neutral source rate of 0.8 tons/s for Voyager 1 and 2.4 tons/s for Voyager 2 (Table 2). This event was not connected to specific observations of volcanic activity or the sodium nebula.

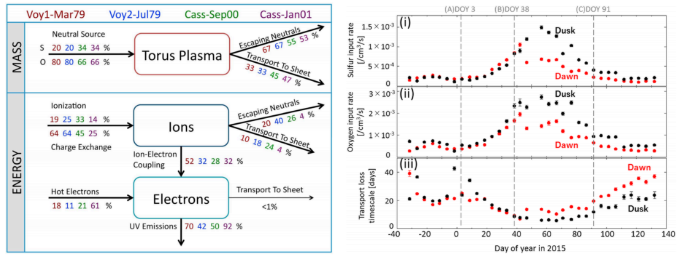

2.6.4 Mass and energy flow in the Io plasma torus

A physical chemistry model has enabled us to investigate mass and energy flows through the Io plasma torus (Copper et al., 2016; Delamere and Bagenal, 2003; Delamere et al., 2004; 2005; Hikida et al., 2020; Nerney et al., 2017; Nerney and Bagenal, 2020; Yoshioka et al., 2018). Figure 20 shows the derived mass and energy flow based on different plasma torus measurements. Hot electrons and pickup of fresh ions resulting from electron-impact ionization and charge exchanges are the main sources of energy to the torus. Mass loss from the plasma torus is caused by fast neutrals and outward plasma transport. In general, the fast neutral contribution is larger than the plasma transport. Detailed mass and energy flows for each process are described in Nerney and Bagenal (2020).

\

\ Source location of the ions. One of the remaining issues is whether the source location is close to the immediate region around Io (atmosphere and corona) or the neutral clouds far from Io. Simulations and Galileo measurements suggest that only a small fraction of ions (~20%) are fed directly into the torus from Io (Bagenal et al. 1997, Saur et al. 2003, and Section 2.4). The supply from the neutral clouds is not well characterized, because the bulk (S and O) neutral clouds themselves are not characterized in detail by observations due to their dim intensity (Section 2.5). Koga et al. (2018b) estimated the source rate of O + from their O neutral clouds at 400 kg/s, confirming the importance of the remote source.

\ Neutral source rate and transport timescales. Delamere et al. (2004) found that the total radiated power from the torus increases by only 25% in response to the factor ~3 change in the neutral supply rate they had derived (Section 2.6.3), and argued that the energy input is diverted by increased losses from the torus through fast neutral and outward plasma transport besides the radiation. Yoshioka et al. (2018) deduced radial distributions of the plasma torus in the spring of 2015 and revealed a higher neutral source rate (~3 tons/s) and a 2-4 times faster outward transport timescale (~10 days) than those during a quiescent period (~0.7 tons/s and ~34 days, respectively). Hikida et al. (2020) derived a time series of the neutral source rate and the transport timescale and showed that the transport timescale decreased soon after the source rate increased (Figure 19, right). The neutral source rate and radial transport time scale derived from various measurements are summarized in Table 2. The source rate varies between 0.7 tons/s and 3.1 tons/s. The loss timescale of the outward transport increases (decreases) as the neutral source rate decreases (increases). Koga et al. (2019) compared the time variations of the oxygen atom emission with that of the oxygen ion and argued that the lifetime of the oxygen ion decreased to ~20 days during the active period, which was about half of that in the quiescent period. These results suggest that the Io plasma torus is consistent with a loss-limited system (see Section 2.6.2).

\

\ Hot electrons. The physical chemistry model also shows that a small fraction of the hot electrons is an important source of energy for the torus (Delamere and Bagenal, 2003; Delamere et al., 2005; Nerney and Bagenal, 2020) representing 0.3 to 1% of the torus thermal electron population. The source mechanism of these hot electrons remains undetermined. There are two hypotheses for the origin of this hot population. One is local heating within the magnetic flux tubes connected to the plasma torus (Coffin et al., 2022; Copper et al., 2016; Hess et al., 2011). The Galileo spacecraft observed a suprathermal electron population in the inward moving flux tube (Frank and Paterson, 2000). The beams of supra-thermal electrons within the flux tube suggest the low-altitude acceleration region.

\ Another idea is that the hot electrons are injected from outside the torus. Yoshioka et al. (2014; 2018) and Hikida et al. (2020) showed that the hot electron density decreases gradually with decreasing radial distance despite the short collisional cooling time scale, suggesting that global inward transport of flux tubes containing hot plasma continuously supplies hot electrons to the plasma torus. Assuming that the cooling time is determined by the Coulomb coupling between hot and core electrons, the timescales for the inward transport across the torus were estimated to be 16 ± 3 h (~2.5 km/s) during the stable torus period and 9.4 ± 1.0 h (~4.3 km/s) during the enhanced torus period. These values are in agreement with those estimated from Galileo in situ measurements (Hikida et al. 2020). Yoshikawa et al. (2016; 2017) and Suzuki et al. (2018) found a short-lived brightening of the plasma torus following the transient auroral brightening. The torus brightness increased by no more than 10%, and the brightening does not last long (< 24 h), indicating that the contribution of the transient event is too small to sustain the plasma torus radiation. This suggests that the hot electron injection into the plasma torus is maintained in a steady manner.

\ Both ideas of the source of hot electrons assume that the electrons are contained in an inward moving flux tube. Flux tube interchange motion is one of the accepted processes that transport Io-genic plasma outward and hot magnetospheric plasma inward although the spatial structure and temporal evolution of the exchange process have not yet been determined. Further observations are needed to characterize the interchange process in the inner magnetosphere and to clarify the origin of the hot electron population.

2.6.5. Energetic ions

Role for heating and stabilization. Energetic ions have been discussed in terms of heating sources and stabilization mechanisms for the Io plasma torus. Schreier et al. (1998) considered hot ion populations diffusing inward as an external energy input to the torus. Based on measurements of the hot ion population made by the Galileo spacecraft (Mauk et al., 2004), the density of the hot ions is insufficient to explain the thermal electron temperature in the torus (Delamere et al. 2005). The outward gradient of plasma mass density in the plasma torus is sufficient to develop the interchange instability. It has been argued that there must be some regulating processes for the outward transport of Io-genic plasma to keep the torus structure stable (e.g., Thomas et al., 2004). One possibility proposed is the "ring current impoundment" (Siscoe et al., 1981; Southwood and Kivelson, 1987), where the outward gradient of torus density is balanced by an opposite pressure gradient of energetic plasmas that surrounds the torus. Mauk et al. (1998; 2004) showed that the hot plasma pressures that can impound Io-genic plasma were substantially depleted during the Galileo mission, as compared with those during the Voyager era. Ongoing Juno observation of energetic particles inside the Europa orbit will provide an opportunity to measure the hot plasma pressure and investigate whether it has a role to impede the outward transport of the Io-genic plasma. An alternative mechanism for impeding the outward transport is "velocity shear impoundment" (Pontius et al., 1998).

\ Diagnostic for the neutral environment. The depletion of energetic ions in the plasma torus is thought to be related to the neutral cloud in the region between Europa and Io’s orbits. The neutral clouds around Io and Europa are important for loss of energetic ions through charge exchange interaction (Mauk et al., 2003; 2004). Lagg et al. (1998) proposed charge exchange with neutrals as an explanation for energy dependent losses of energetic protons measured in Io’s orbit, suggesting that the ion dropouts could be a diagnostic for the neutral density in the neutral cloud. However, Mauk et al. (2022) argued, based on a neutral cloud model by Smith et al. (2019), that near Io’s orbit charge exchange with low energy ions would dominate over charge exchange with neutrals.

\ Observations of energetic ions are a useful tool to study the interaction between moons and magnetospheric plasma as well as their neutral environment. Huybrighs et al. (2024, in review) shows that dropouts of energetic protons (~100 keV) are present during close Io flybys of Galileo. A particle-tracing model demonstrates that the dropouts outside of ~0.5 Io radii are likely dominated by charge exchange with Io’s atmosphere. The dropout structure is sensitive to the density and three dimensional structure of the atmosphere. Thus, measurements of energetic protons provide an additional diagnostic to investigate Io’s atmosphere’s structure, near Io.

\

\

:::info This paper is available on arxiv under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 DEED license.

:::

:::info Authors:

(1) L. Roth, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Space and Plasma Physics, Stockholm, Sweden and a Corresponding author;

(2) A. Blöcker, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Space and Plasma Physics, Stockholm, Sweden and Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, Munich, Germany;

(3) K. de Kleer, Division of Geological and Planetary Sciences, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125 USA;

(4) D. Goldstein, Dept. Aerospace Engineering and Engineering Mechanics, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX USA;

(5) E. Lellouch, Laboratoire d’Etudes Spatiales et d’Instrumentation en Astrophysique (LESIA), Observatoire de Paris, Meudon, France;

(6) J. Saur, Institute of Geophysics and Meteorology, University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany;

(7) C. Schmidt, Center for Space Physics, Boston University, Boston, MA, USA;

(8) D.F. Strobel, Departments of Earth & Planetary Science and Physics & Astronomy, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD 21218, USA;

(9) C. Tao, National Institute of Information and Communications Technology, Koganei, Japan;

(10) F. Tsuchiya, Graduate School of Science, Tohoku University, Sendai, Japan;

(11) V. Dols, Institute for Space Astrophysics and Planetology, National Institute for Astrophysics, Italy;

(12) H. Huybrighs, School of Cosmic Physics, DIAS Dunsink Observatory, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin 15, Ireland, Space and Planetary Science Center, Khalifa University, Abu Dhabi, UAE and Department of Mathematics, Khalifa University, Abu Dhabi, UAE;

(13) A. Mura, XX;

(14) J. R. Szalay, Department of Astrophysical Sciences, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, USA;

(15) S. V. Badman, Department of Physics, Lancaster University, Lancaster, LA1 4YB, UK;

(16) I. de Pater, Department of Astronomy and Department of Earth & Planetary Science, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA;

(17) A.-C. Dott, Institute of Geophysics and Meteorology, University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany;

(18) M. Kagitani, Graduate School of Science, Tohoku University, Sendai, Japan;

(19) L. Klaiber, Physics Institute, University of Bern, 3012 Bern, Switzerland;

(20) R. Koga, Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Nagoya University, Nagoya, Aichi 464-8601, Japan;

(21) A. McEwen, Department of Astronomy and Department of Earth & Planetary Science, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA;

(22) Z. Milby, Division of Geological and Planetary Sciences, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125 USA;

(23) K.D. Retherford, Southwest Research Institute, San Antonio, TX, USA and University of Texas at San Antonio, San Antonio, Texas, USA;

(24) S. Schlegel, Institute of Geophysics and Meteorology, University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany;

(25) N. Thomas, Physics Institute, University of Bern, 3012 Bern, Switzerland;

(26) W.L. Tseng, Department of Earth Sciences, National Taiwan Normal University, Taiwan;

(27) A. Vorburger, Physics Institute, University of Bern, 3012 Bern, Switzerland.

:::

\

This content originally appeared on HackerNoon and was authored by Diurnal

Diurnal | Sciencx (2025-03-05T11:00:04+00:00) Mass and Energy Flow in Jupiter’s Magnetosphere. Retrieved from https://www.scien.cx/2025/03/05/mass-and-energy-flow-in-jupiters-magnetosphere/

Please log in to upload a file.

There are no updates yet.

Click the Upload button above to add an update.