This content originally appeared on raganwald.com and was authored by Reginald Braithwaite

foreword

This talk was given at NDC London on January 14, 2016. This is not a literal transcript: A selection of the original slides are shown here, along with some annotations explaining the ideas presented.

Part I: The Basics

“In object-oriented programming, the command pattern is a behavioural design pattern in which an object is used to encapsulate all information needed to perform an action or trigger an event at a later time.”

We will review the command pattern’s definition, then look at some interesting applications. We’ll see why what matters about the command pattern is the underlying idea that behaviour can be treated as a first-class entity in its own right.

The command pattern was popularized by the 1994 book Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software. But it’s 2016. Why do we care? Why is it worth another look?

At that time, most software ran on the desktop or in a client-server environment. Distributed software was relatively exotic. So naturally, the examples given of the command pattern in use were often those applicable to single users. Like “undo,” writing macros, or perhaps displaying a progress bar.

Nevertheless, the underlying idea of the command pattern becomes particularly interesting when applied to parallel and distributed software, whether we are thinking of job queues, thread pools, or algorithms that provide eventual consistency across a distributed system.

In 2016, software is parallel and distributed by default. And the command pattern deserves another look, with fresh eyes.

The “canonical example” of the command pattern is working with mutable data. Here’s one such example, chosen because it fits on a couple of sides:

class Buffer {

constructor (text = '') { this.text = text; }

replaceWith (replacement, from = 0, to = this.text.length) {

this.text = this.text.slice(0, from) +

replacement +

this.text.slice(to);

return this;

}

toString () { return this.text; }

}

let buffer = new Buffer();

buffer.replaceWith(

"The quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog"

);

buffer.replaceWith("fast", 4, 9);

buffer.replaceWith("canine", 40, 43);

//=> The fast brown fox jumped over the lazy canine

We have buffer that contains some plain text, and it has a single behaviour, a replaceWith method that replaces a selection of the buffer with some new text. Insertions can be managed by replacing a zero-length selection, and deletions can be handled by replacing a selection with the empty string.

Ten years ago, Steve Yegge described OOP as a Kingdom of Nouns: Everything is an object and objects own their behaviours.

There is a very explicit idea that objects model entities in the real world, and methods model changes to those entities. Objects are “first-class:” They can be stored in variables, we can query them for their properties, and we can transform them into different states or different entities altogether.

Many languages also permit us to treat methods as first-class entities. In Python, we can easily extract a bound method from an object. In Ruby, we can manipulate both bound and unbound methods. In JavaScript, methods are just functions.

Typically, treating methods as first-class entities is rarer than treating “nouns” as first-class entities, but it is possible. This forms the basis of meta-programming techniques like writing method decorators.

But the command pattern concerns itself with invocations. An invocation is a specific method, invoked on a specific receiver, with specific parameters:

Classes are to instances as methods are to invocations.

If an invocation was a first-class entity, we could store it in a variable or data structure. Let’s try it:

class Edit {

constructor (buffer, {replacement, from, to}) {

this.buffer = buffer;

Object.assign(this, {replacement, from, to});

}

doIt () {

this.buffer.text =

this.buffer.text.slice(0, this.from) +

this.replacement +

this.buffer.text.slice(this.to);

return this.buffer;

}

}

class Buffer {

constructor (text = '') { this.text = text; }

replaceWith (replacement, from = 0, to = this.text.length) {

return new Edit(this, {replacement, from, to});

}

toString () { return this.text; }

}

let buffer = new Buffer(), jobQueue = [];

jobQueue.push(

buffer.replaceWith(

"The quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog"

)

);

jobQueue.push( buffer.replaceWith("fast", 4, 9) );

jobQueue.push( buffer.replaceWith("canine", 40, 43) );

while (jobQueue.length > 0) {

jobQueue.shift().doIt();

}

//=> The fast brown fox jumped over the lazy canine

Since we’re taking an OO approach, we’ve created an Edit class that represents invocations. Each instance is an invocation, and thus we can create new invocations with new Edit(...) and actually perform the invocation with .doIt().

In this example, we’ve created a job queue, deferring a number of invocations until we pop them off the queue and perform them. Note that “invoking” methods on a buffer no longer does anything: Instead, they return invocations we manipulate explicitly.1

This is the canonical way to “do commands” in OOP: Make them instances of a class and perform them with a method. There are other ways to implement the command pattern, and it can be implemented in FP as well, but for our purposes this is enough to explore its applications.

We can also query commands. Naturally, we do this by implementing methods that report on some critical characteristic, like a command’s scope. For simplicity, we won’t implement a .scope() method that reports the extent of an edit’s selection, since JavaScript encourages unencapsulated direct property access.

But we can report on the amount by which an edit lengthens or shortens a buffer:

class Edit {

netChange () {

return this.from - this.to + this.replacement.length;

}

}

let buffer = new Buffer();

buffer.replaceWith(

"The quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog"

).netChange();

//=> 44

buffer.replaceWith("fast", 4, 9).netChange();

//=> -1

This can be useful.

First-class entities can also be transformed. And here we come to the most interesting application of commands. Here’s a .reversed() method that returns the inverse of any edit:

class Edit {

reversed () {

let replacement = this.buffer.text.slice(this.from, this.to),

from = this.from,

to = from + this.replacement.length;

return new Edit(buffer, {replacement, from, to});

}

}

let buffer = new Buffer(

"The quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog"

);

let doer = buffer.replaceWith("fast", 4, 9),

undoer = doer.reversed();

doer.doIt();

//=> The fast brown fox jumped over the lazy dog

undoer.doIt();

//=> The quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog

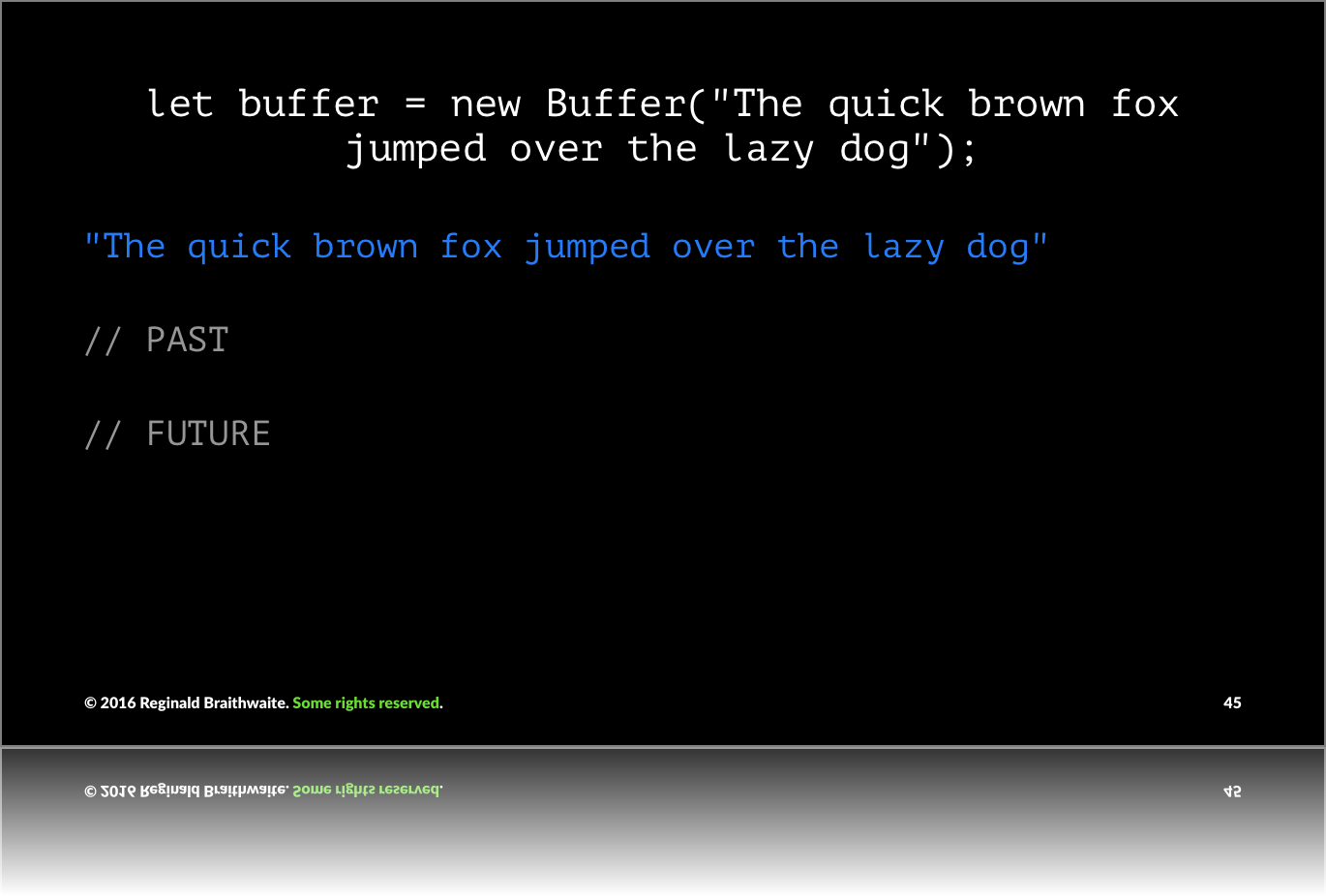

Let’s put our storing and transforming together. Instead of returning a command from the replaceWith method, we’ll create a doer command, and push its reverse onto a history stack. We’ll then invoke doer.doIt() to actually perform the replacement on the buffer:

class Buffer {

constructor (text = '') {

this.text = text;

this.history = [];

this.future = [];

}

}

class Buffer {

replaceWith (replacement, from = 0, to = this.length()) {

let doer = new Edit(this, {replacement, from, to}),

undoer = doer.reversed();

this.history.push(undoer);

this.future = [];

return doer.doIt();

}

}

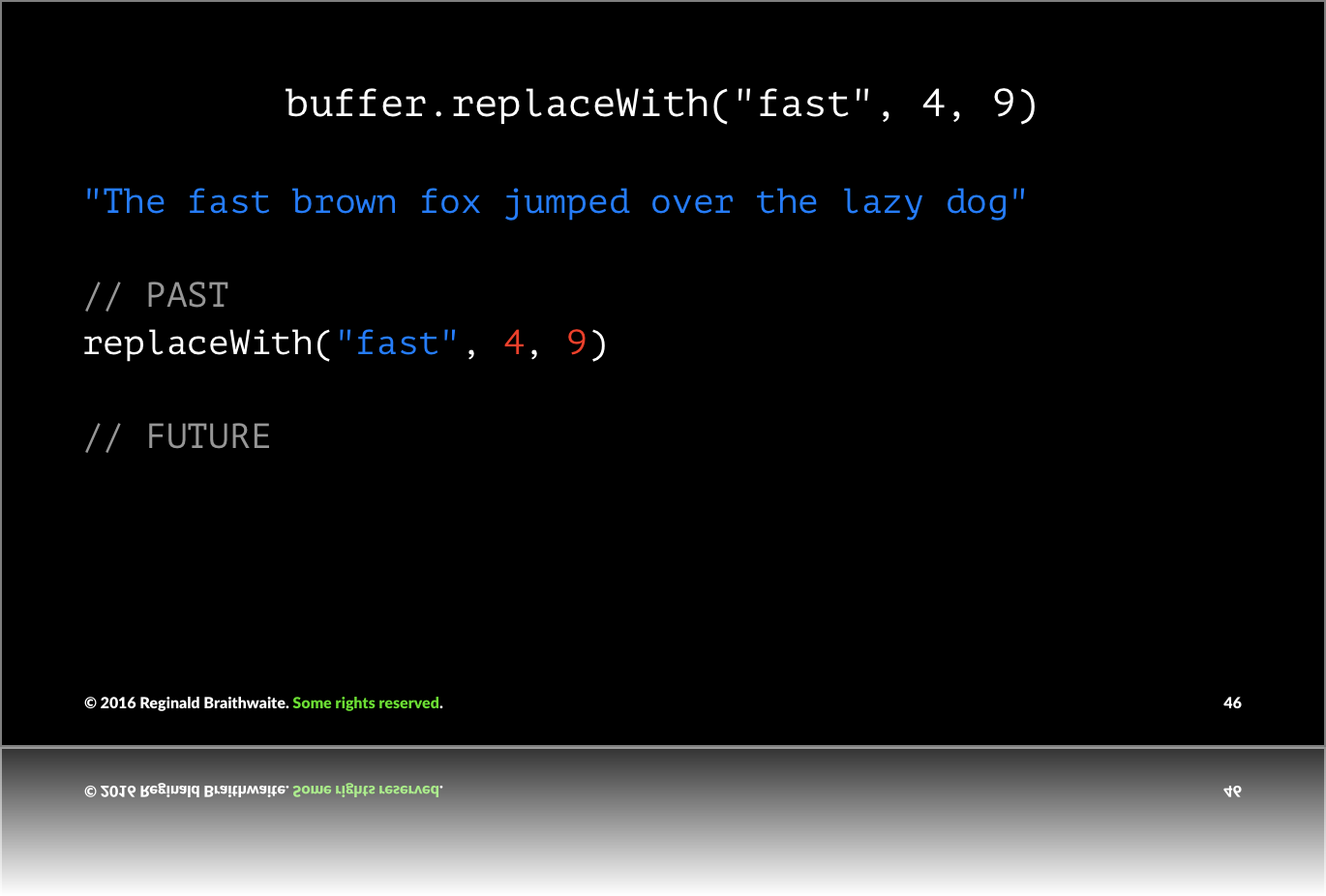

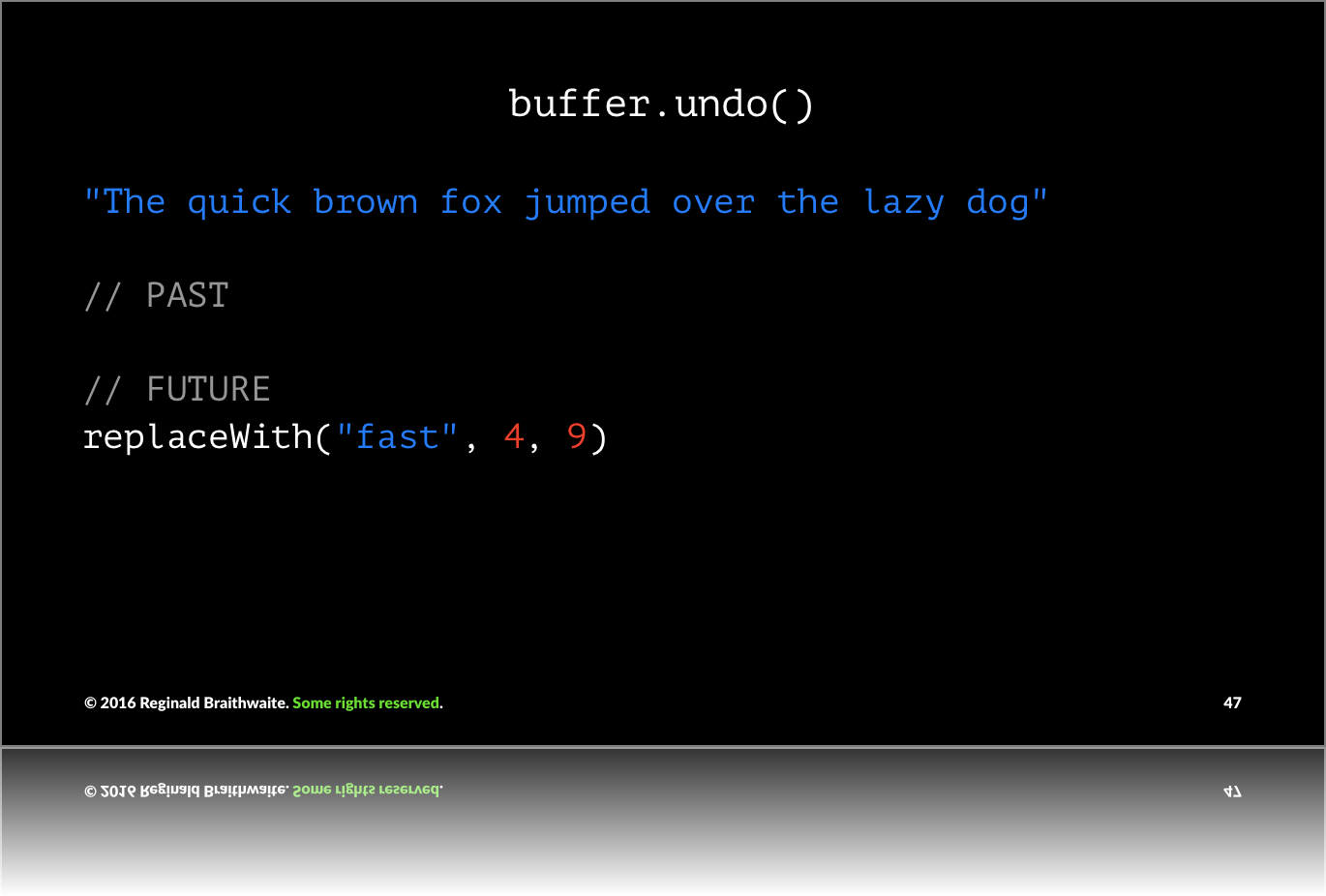

Implementing undo is straightforward: Pop an undoer from the stack, create a redoer for later, push the redoer onto a future stack, and invoke the undoer:

class Buffer {

undo () {

let undoer = this.history.pop(),

redoer = undoer.reversed();

this.future.unshift(redoer);

return undoer.doIt();

}

}

let buffer = new Buffer(

"The quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog"

);

buffer.replaceWith("fast", 4, 9)

//=> The fast brown fox jumped over the lazy dog

buffer.replaceWith("canine", 40, 43)

//=> The fast brown fox jumped over the lazy canine

buffer.undo()

//=> The fast brown fox jumped over the lazy dog

buffer.undo()

//=> The quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog

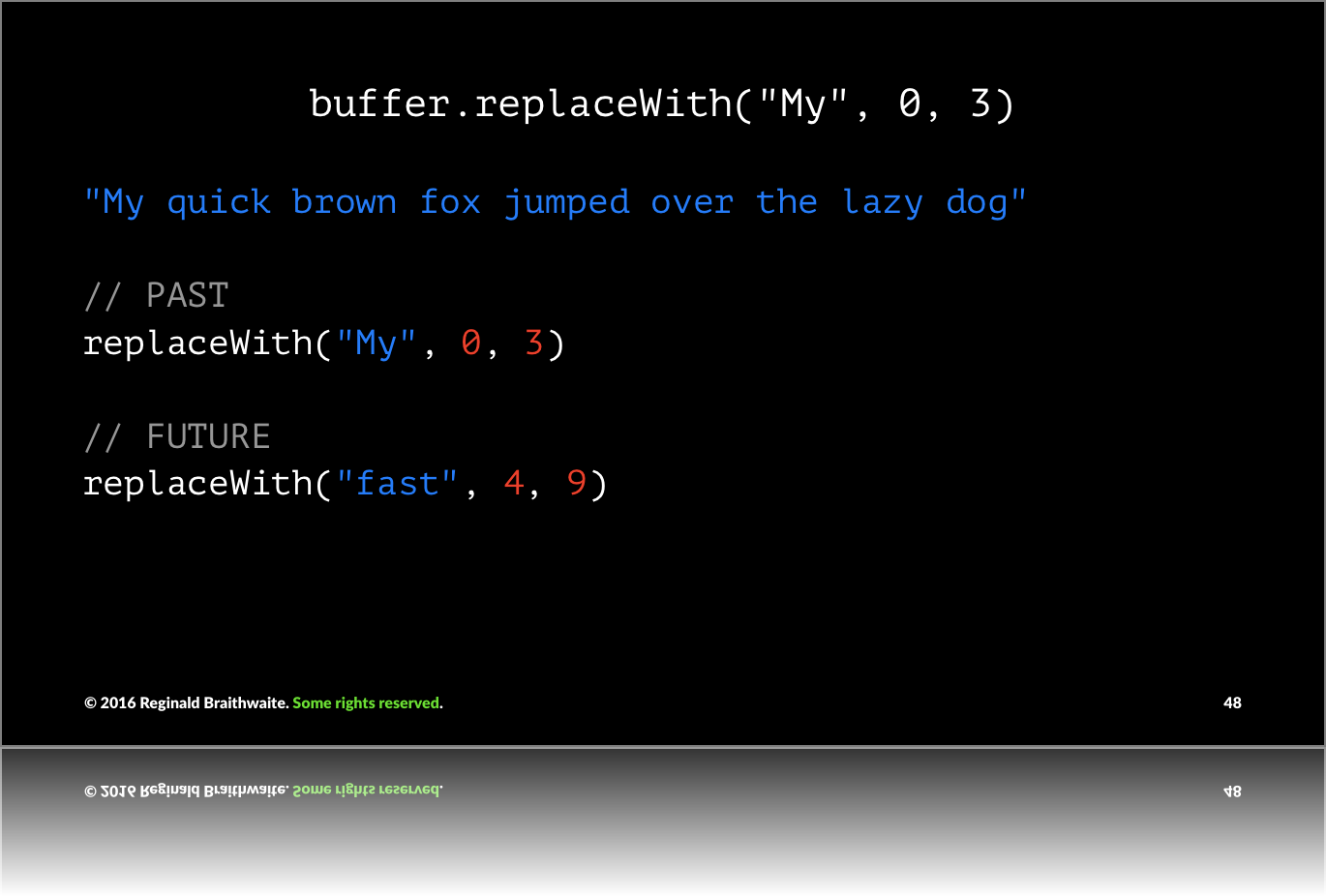

Redoing something we’ve undone is now simple:

class Buffer {

redo () {

let redoer = this.future.shift(),

undoer = redoer.reversed();

this.history.push(undoer);

return redoer.doIt();

}

}

buffer.redo()

//=> The fast brown fox jumped over the lazy dog

buffer.redo()

//=> The fast brown fox jumped over the lazy canine

And again, its reverse goes onto the history so we can toggle back and forth between undoing and redoing.

Like the slide says, this is the basic idea you’ll find in the GoF book as well as in 1980s tomes on OO programming. I recall an Object Pascal book using this pattern to implement undo within the MacApp framework in the late 1980s.

Our example hits all three of the characteristics of invocations as first-class entities. But that isn’t really enough to “provoke our intellectual curiosity.” So let’s consider a more interesting direction.

coupling through time

We begin by asking a question.

Recall this code for replacing text in a buffer:

class Buffer {

replaceWith (replacement, from = 0, to = this.length()) {

let doer = new Edit(this, {replacement, from, to}),

undoer = doer.reversed();

this.history.push(undoer);

this.future = [];

return doer.doIt();

}

}

Note that when we perform a replacement, we execute this.future = [], throwing away any “redoers” we may have accumulated by undoing edits.

Let’s try not throwing it away:

class Buffer {

replaceWith (replacement, from = 0, to = this.length()) {

let doer = new Edit(this, {replacement, from, to}),

undoer = doer.reversed();

this.history.push(undoer);

// this.future = [];

return doer.doIt();

}

}

let buffer = new Buffer(

"The quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog"

);

buffer.replaceWith("fast", 4, 9);

//=> The fast brown fox jumped over the lazy dog

buffer.undo();

//=> The quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog

buffer.replaceWith("My", 0, 3);

//=> My quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog

We’ve performed a replacement, then we’ve undone the replacement, restoring the buffer to its original state. Then we performed a different replacement. But since our code no longer discards the future, a redoer is still in this.future.

Unfortunately, the result is not what we expect semantically:

What went wrong?

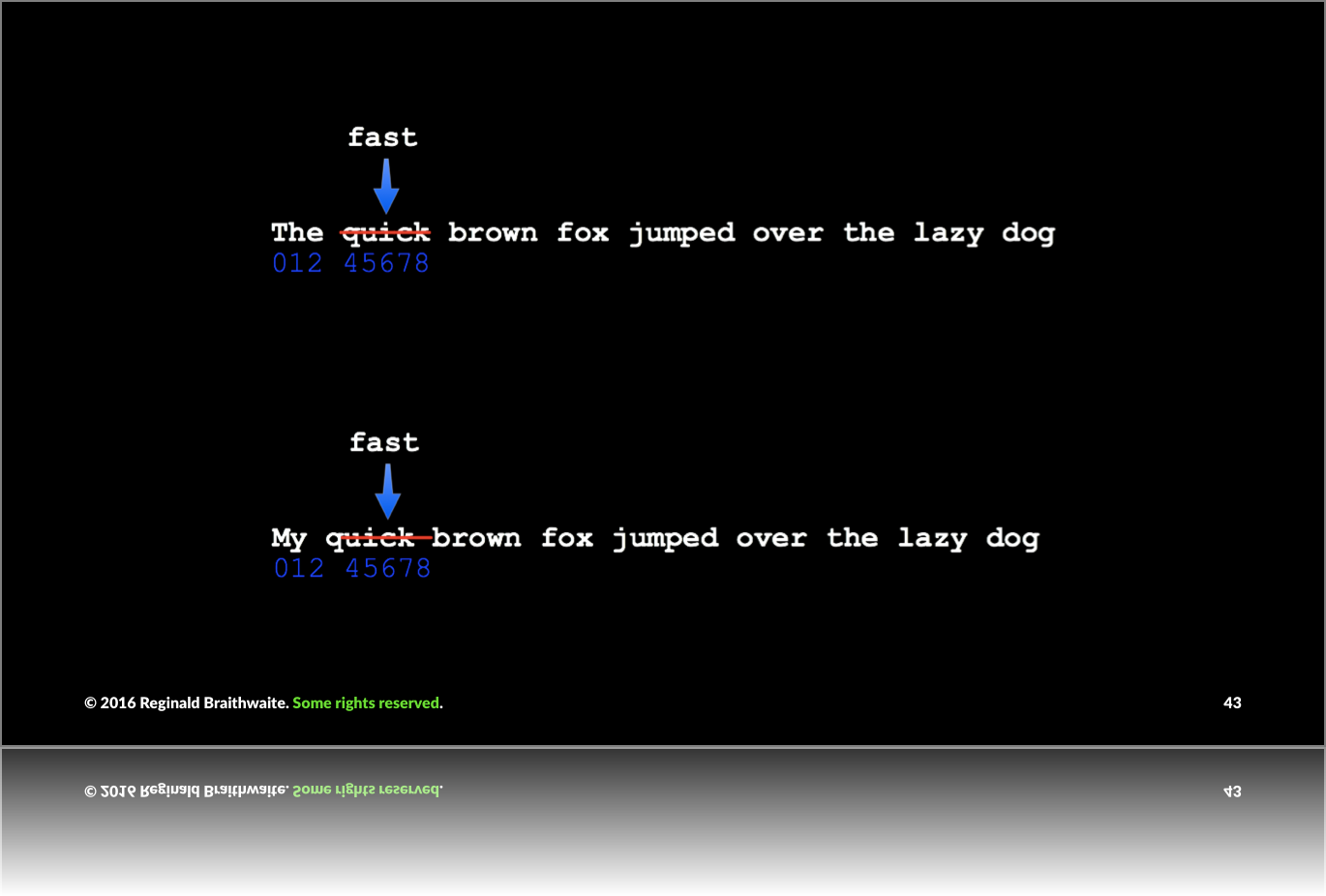

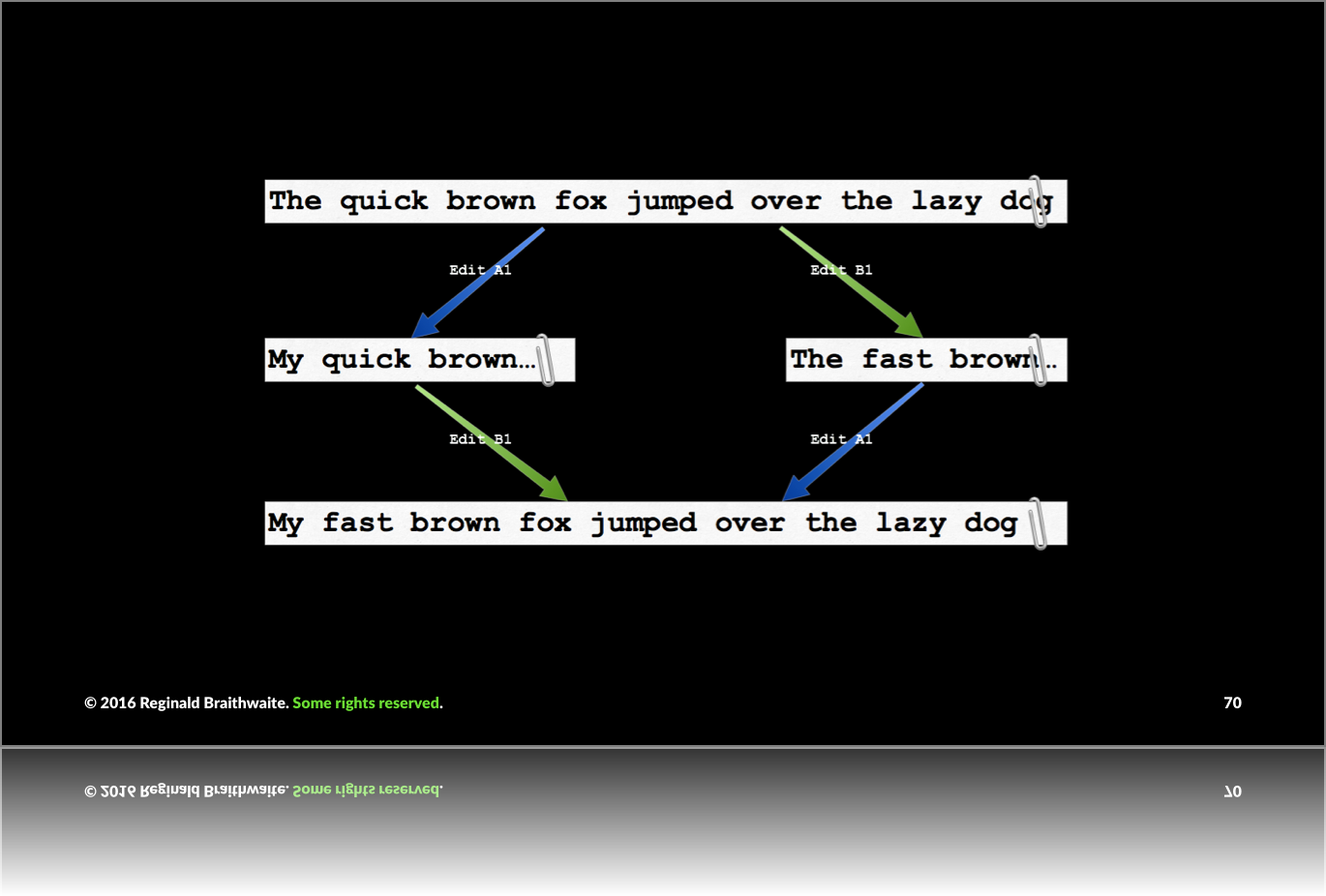

As the illustration shows, when we first performed .replaceWith('fast', 4, 9), it replaced the characters q, u, i, c, and k, because those were in the selection between 4 and 9 of the buffer.

Our redoer in the future performs this same replacement, but now that we’ve invoked .replaceWith('My', 0, 3), the characters in the selection between 4 and 9 are now u, i, c, k, and ` `, a blank space.

Invoking .replaceWith('My', 0, 3) has moved the part of the buffer we semantically want to replace.

If we step through the invocations, we can see that when we first invoke .replaceWith('fast', 4, 9), no other edits were invoked before it.

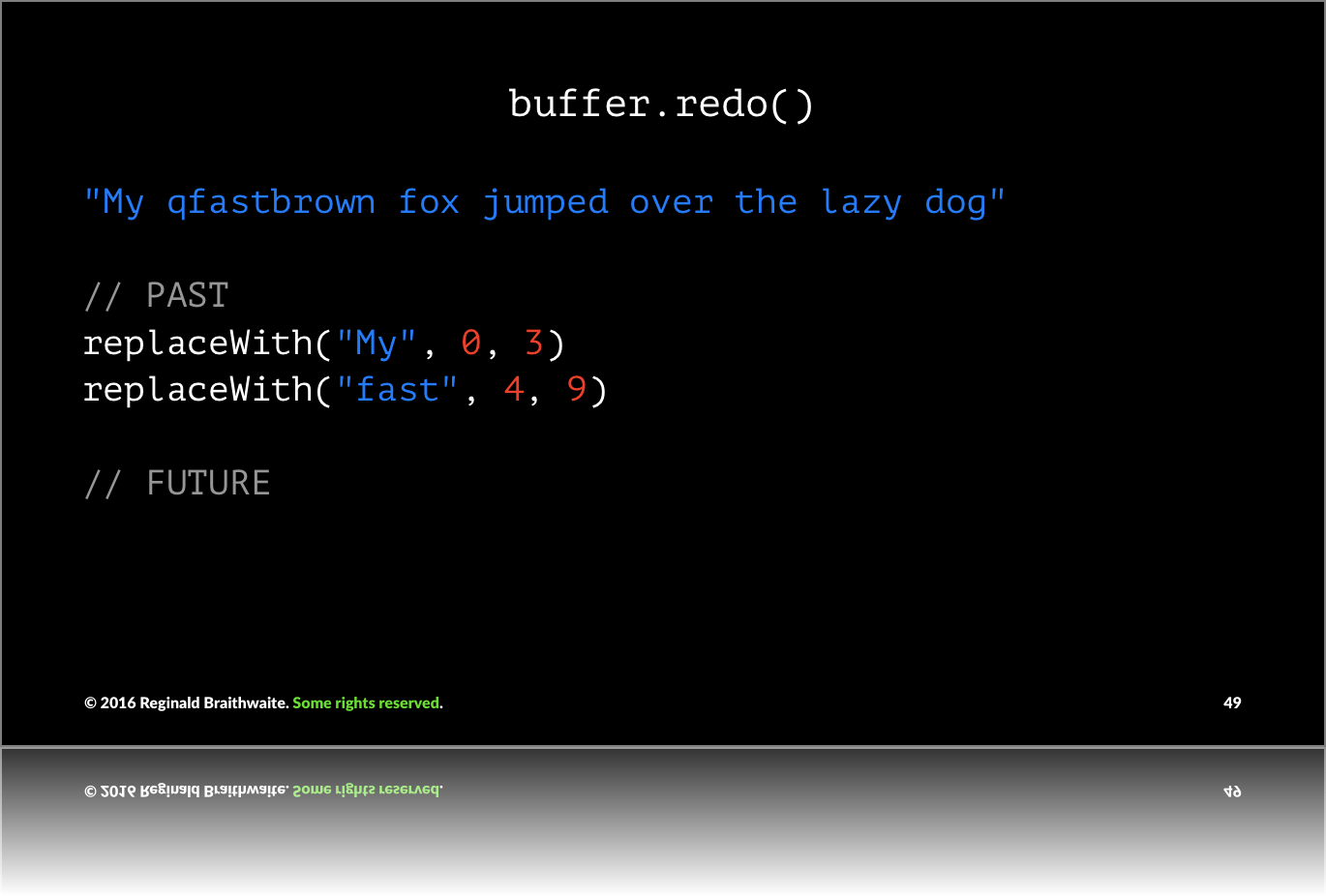

Then after undoing it and invoking .replaceWith('My', 0, 3), we have created a situation where .replaceWith('My', 0, 3) is now before .replaceWith('fast', 4, 9) in the future. If we invoke it, we see this clearly as it moves to the past, but it is now preceded by .replaceWith('My', 0, 3):

It turns out that commands are first-class entities, but there is a spooky relationship between them and the models they manipulate, thanks to cause-and-effect. They aren’t 100% independent entities that can be invoked in any order, any number of times.

Commands mutating a model have a semantic dependency on all of the commands that have mutated the model in the past. If you change the order of commands, they may no longer be semantically valid. In some cases, they could even become logically invalid.

Semantically, we can think that if we alter the history of edits before invoking a command, we are altering the meaning of the command. Replacing The with My altered the meaning of .replaceWith('fast', 4, 9).

adjusting for changes in history

Let’s go about fixing this specific problem, that of commands altering the position of other commands.2 We being with another query, we can ask whether a particular edit is before another edit, meaning that A is before B if A affects a selection of text that entirely precedes the selection affected by B.

let buffer = new Buffer(

"The quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog"

);

let fast = new Edit(

buffer,

{ replacement: "fast", from: 4, to: 9 }

);

let my = new Edit(

buffer,

{ replacement: "My", from: 0, to: 3 }

);

class Edit {

isBefore (other) {

return other.from >= this.to;

}

}

fast.isBefore(my);

//=> false

my.isBefore(fast);

//=> true

Equipped with .isBefore and .netChange(), we can write .prependedWith method that takes an edit, and returns a new version of the edit that corrects for any change caused by prepending another edit into its history.

There are two cases we cover: If we write a.prependedWith(b), and a is before b, then we return a since b doesn’t change its semantic meaning. But if we write a.prependedWith(b), and b is before a, then we return a copy of a that has been adjusted by the amount of b’s net change:

class Edit {

prependedWith (other) {

if (this.isBefore(other)) {

return this;

}

else if (other.isBefore(this)) {

let change = other.netChange(),

{replacement, from, to} = this;

from = from + change;

to = to + change;

return new Edit(this.buffer, {replacement, from, to})

}

}

}

my.prependedWith(fast)

//=> buffer.replaceWith("My", 0, 3)

fast.prependedWith(my)

//=> buffer.replaceWith("fast", 3, 8)

my.prependedWith(fast)

//=> buffer.replaceWith("My", 0, 3)

fast.prependedWith(my)

//=> buffer.replaceWith("fast", 3, 8)

With this in hand, we see what to do with this.future: Whenever we invoke a fresh command, we must replace all of the edits in the future with versions prepended with the command we’re invoking, thus adjusting them to maintain the same semantic meaning:

class Buffer {

replaceWith (replacement, from = 0, to = this.length()) {

let doer = new Edit(this, {replacement, from, to}),

undoer = doer.reversed();

this.history.push(undoer);

this.future = this.future.map(

(edit) => edit.prependedWith(doer)

);

return doer.doIt();

}

}

let buffer = new Buffer(

"The quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog"

);

buffer.replaceWith("fast", 4, 9);

//=> The fast brown fox jumped over the lazy dog

buffer.undo();

//=> The quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog

buffer.replaceWith("My", 0, 3);

//=> My quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog

buffer.redo();

Now we get the correct result!

the bigger picture

Once upon a time, “undo” was a magical feature for single users. It transformed the software experience for users, because they could act without fear of making irreversible catastrophic mistakes. There was a natural progression to undo and redo stacks. But it was rare that applications went further.

Only the most esoteric would surface the undo and redo stacks, permitting execution of arbitrary commands from the redo stack, or maintained the redo stack after performing new edits (as we’ve implemented here). This is a neat feature, but challenging to design into an application in the “real world.” It’s challenging to set user expectations about what the redo command will do.3

But not all implementations of commands have a direct representation in the user experience. And if we put aside the problem of user experience, we have a very strong takeaway from dealing with maintaining the future while inserting new edits into the history. While it’s just one limited example, it hints at being able to arbitrarily manipulate history, inserting, removing, or reordering edits as we desire.

This is a very powerful concept: Typically, we are slaves to mutable state. It moves forward inexorably. Taming it is a struggle. But commands suggest a way to take control.

Part II: Software in a Distributed World

Alice and Bob are writing a screenplay. Naturally, their editors use our buffers and edits:

let alice = new Buffer(

"The quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog"

);

let bob = new Buffer(

"The quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog"

);

To keep the code simple, we’ll omit some of the moving parts to support undoing edits from our command-oriented Buffer class:

class Buffer {

constructor (text = '') {

this.text = text;

this.history = [];

}

replaceWith (replacement, from = 0, to = this.length()) {

let edit = new Edit(this,

{replacement, from, to}

);

this.history.push(edit);

return edit.doIt();

}

}

Now we want to synchronize the screenplay, so that Alice can see Bob’s change, and Bob can see Alice’s change. So, naturally, Alice sends Bob her change, and Bob sends Alice his change. We want to apply those changes so that we end up with both Alice and Bob looking at identical buffers.

What we want to do looks like this:

Alice and Bob each perform a different edit, causing their buffers to diverge. We want to apply each other’s edits in such a way that they converge back to a consistent view of the buffer.

We can try that:

class Buffer {

append (theirEdit) {

this.history.forEach( (myEdit) => {

theirEdit = theirEdit.prependedWith(myEdit);

});

return new Edit(this, theirEdit).doIt();

}

appendAll(otherBuffer) {

otherBuffer.history.forEach(

(theirEdit) => this.append(theirEdit)

);

return this;

}

}

Now we can write alice.appendAll(bob) to apply all of Bob’s edits to Alice’s copy of the buffer. And we can write bob.appendAll(alice) to apply all of Alice’s edits to Bob’s copy of the buffer. Problem solved?

alice.appendAll(bob);

//=> My fast brown fox jumped over the lazy dog

bob.appendAll(alice);

//=> My fast brown fox jumped over the lazy dog

This appears to work: By prepending the exiting edits onto edits being appended to a buffer, we transform the new edits to producet the same result, synchronizing the buffers.

Unfortunately, there’s a bug.

A big bug!

What happens if we try to append again? Since neither Alice nor Bob have made any further edits, the buffers should remain unchanged. But they don’t:

alice.appendAll(bob);

//=> My fastbrown fox jumped over the lazy dog

bob.appendAll(alice);

//=> Myfast brown fox jumped over the lazy dog

Our append methods are applying each edit all over again. To fix that, we have to modify our algorithm to pay attention to whether edits already exist in a buffer or edit’s history. First, let’s upgrade our edits and give them a guid we can use to identify them, as well as a set of the guids of the edits that came before them:

let GUID = () => {

let _p8 = (s) => {

let p = (Math.random().toString(16)+"000000000").substr(2,8);

return s ? "-" + p.substr(0,4) + "-" + p.substr(4,4) : p ;

}

return _p8() + _p8(true) + _p8(true) + _p8();

}

class Edit {

constructor (buffer,

{ guid = GUID(), befores = new Set(),

replacement, from, to }) {

this.buffer = buffer;

befores = new Set(befores);

Object.assign(this,

{guid, replacement, from, to, befores});

}

}

Our buffers will also track the guids of the edits in their history:

class Buffer {

constructor (text = '', history = []) {

let befores = new Set(history.map(e => e.guid));

history = history.slice(0);

Object.assign(this, {text, history, befores});

}

share () {

return new Buffer(this.text, this.history);

}

has (edit) { return this.befores.has(edit.guid); }

}

We’ll refactor replaceWith to extract a .perform(edit), it will simplify a lot of what’s coming:

class Buffer {

perform (edit) {

if (!this.has(edit)) {

this.history.push(edit);

this.befores.add(edit.guid);

return edit.doIt();

}

}

replaceWith (replacement,

from = 0, to = this.length()) {

let befores = this.befores,

let edit = new Edit(this,

{replacement, from, to, befores}

);

return this.perform(edit);

}

}

Now our append method can be fixed to prepend every edit with everything in its history, much as we did with fixing redo:

class Buffer {

append (theirEdit) {

this.history.forEach( (myEdit) => {

theirEdit = theirEdit.prependedWith(myEdit);

});

return this.perform(new Edit(this, theirEdit));

}

}

Here’s an updated appendAll that only appends edits that aren’t already in the history. What? We didn’t mention that was another bug in the code? Silly us.4

class Buffer {

appendAll(otherBuffer) {

otherBuffer.history.forEach(

(theirEdit) =>

this.has(theirEdit) || this.append(theirEdit)

);

return this;

}

}

Now we’re finally ready to update the prependedWith method to check whether an edit is “before” another edit, is the same as another edit, or is already in the edit’s history:

class Edit {

prependedWith (other) {

if (this.isBefore(other) ||

this.befores.has(other.guid) ||

this.guid === other.guid) return this;

let change = other.netChange(),

{guid, replacement, from, to, befores} = this;

from = from + change;

to = to + change;

befores = new Set(befores);

befores.add(other.guid);

return new Edit(this.buffer, {guid, replacement, from, to, befores});

}

}

With all these changes in place, Alice and Bob can exchange edits at will.5 Let’s try it!

alice, bob, and carol

Alice, Bob and Carol are writing a screenplay.

let alice = new Buffer(

"The quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog"

);

let bob = alice.share();

//=> The quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog

alice.replaceWith("My", 0, 3);

//=> My quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog

let carol = alice.share();

//=> My quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog

bob.replaceWith("fast", 4, 9);

//=> The fast brown fox jumped over the lazy dog

alice.appendAll(bob);

//=> My fast brown fox jumped over the lazy dog

bob.appendAll(alice);

//=> My fast brown fox jumped over the lazy dog

alice.replaceWith("spotted", 8, 13);

//=> My fast spotted fox jumped over the lazy dog

bob.appendAll(alice);

//=> My fast spotted fox jumped over the lazy dog

carol.appendAll(bob);

//=> My fast spotted fox jumped over the lazy dog

It works!

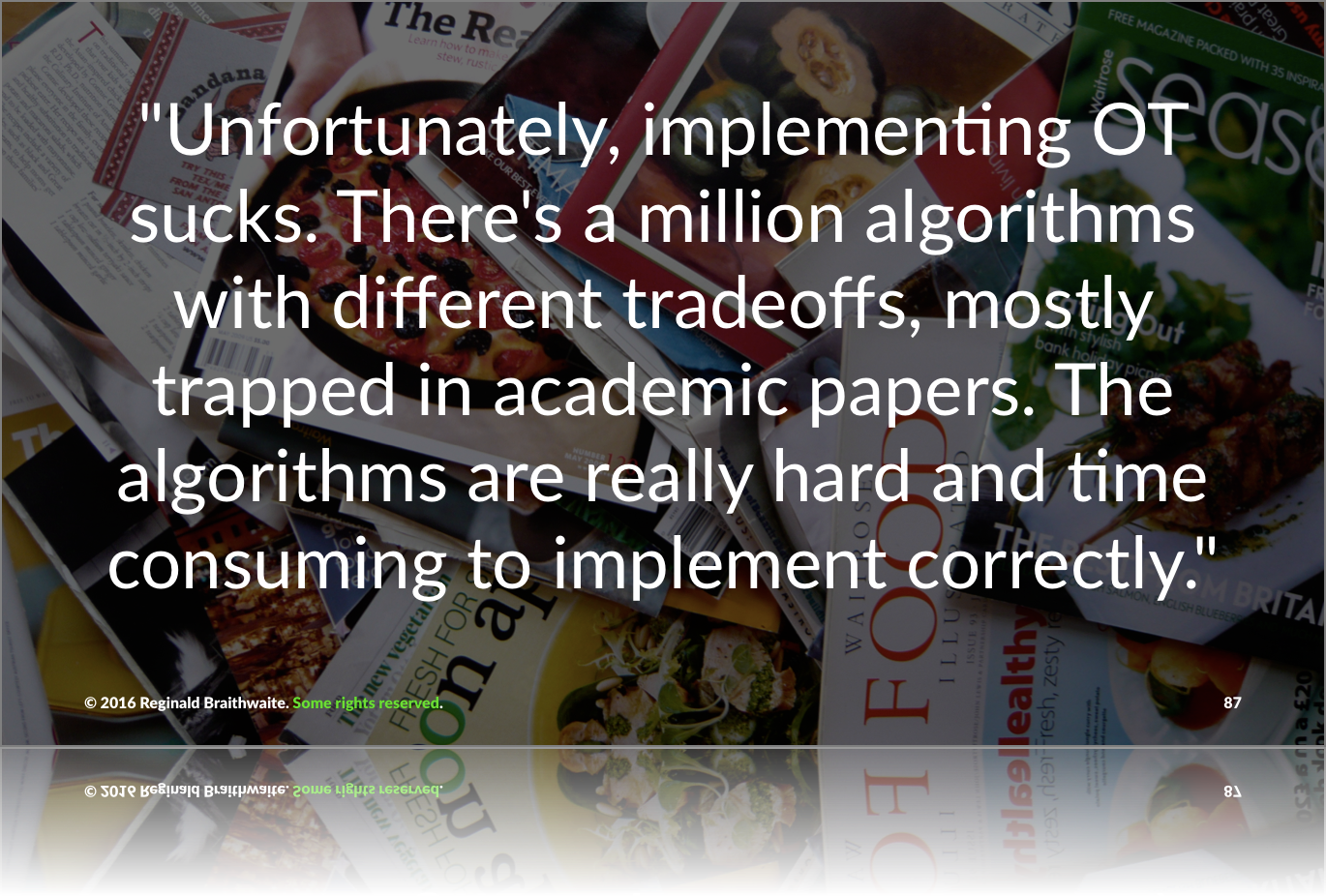

Or rather, it works for some definition of “works.” The algorithm we just implemented is called Operational Transformation, and John Gentle’s quote above is pertinent.

We’ve completely omitted the problem of overlapping edits. We’re working with a remarkably simple data model, a string. Even so, what if Alice, Bob, and Carol each make edits that don’t conflict with each other when compared individually: Can we guarantee that we can apply them in any order and not end up with a conflict?

And if we imagine trying to use these techniques to maintain consistency while multiple users edit a complex data structure with internal references, things get complicated. For example, what if we have users, each of whom have multiple addresses, and one person deletes an address that another person is editing. What happens then?

Our algorithm skipped over undos. Are undo queues local? Or can you undo an edit another user makes?6

OT relies on making a very careful analysis of the different kinds of edits that can be made, and determining exactly how to transform them when prepended by any other edit. Even then, it is hairy.

Recognizing this, people have come up with other mechanisms for distributing edits. Mapping commands 1-1 with user actions is necessary for undo. But it is hard to infer user intentions from their actions: What if instead of selecting a word and replacing it with another, Alice backspaces five times and then types four letters. Is that nine edits? Two edits? Or one?

And it may not be necessary for us to infer actions to synchronize documents. We can, for example, regularly take a diff of the document and send that off to be synchronized. That’s the Differential Synchronization algorithm, and it’s how Google Docs originally worked when Google acquired Writely:

At it’s heart, though, we’re still dealing with the idea that we don’t just treat physical entities–nouns–as our software entities. We also model changes as first-class entities that can be stored, queried, and edited.

Part III: Commands, More Useful Now Than Ever

Working with distributed changes is now a very, very big problem space. Software is no longer living on one device. We chat, we have distributed sessions, we demand eventual consistency from our data.

Everything we do in these areas requires treating changes as first-class entities.

“There are only two hard problems in Computer Science: Cache invalidation, and naming things.”–Phil Karlton

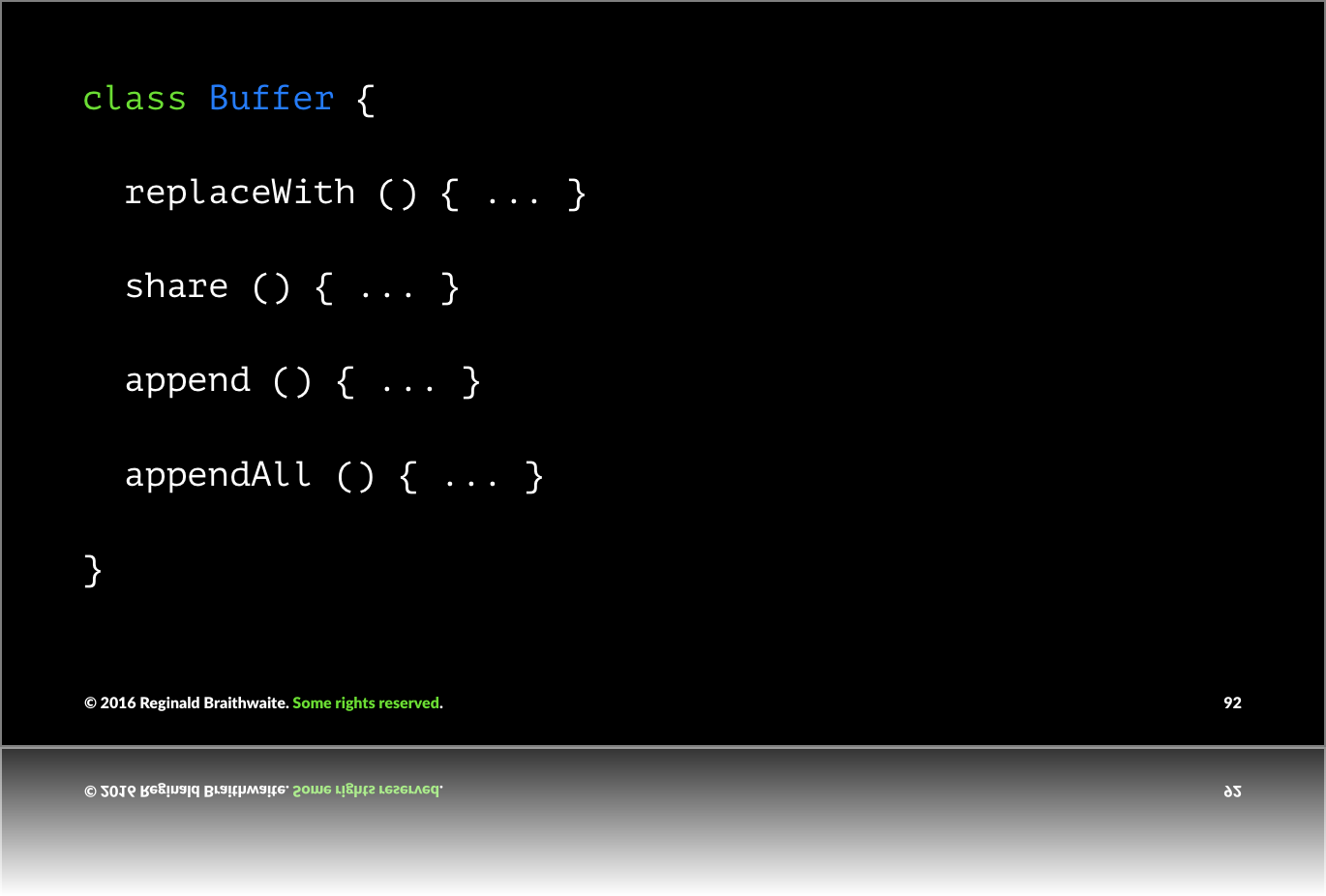

What if we take the names of our Buffer class:

And changed them:

Does this look familiar? We’ve discussed reordering time for an individual user, and we’ve discussed synchronizing changes across distributed users. But we now write software that puts control of cause and effect in the hands of distributed users as well.

Being able to fork repositories, cherry-pick changes to apply, and merge (or rebase) changes is another aspect of the same concept: Changes as first-class entities. What new user models can we develop if we take that kind of thinking to other kinds of software?

Will there one day be a version of PowerPoint that allows someone to submit a pull request to a presentation?7 If there is, it will be because somebody modeled presentations as commands rather than as big binary data blobs.

Getting back to OT and DS, synchronizing data is far more than supporting simultaneous document editing. Database systems often model transactions as commands or collections of commands, and use various types of protocols to permit the commands to execute in parallel without blocking each other.

Replicated data stores use distributed algorithms built out of commands to propagate changes and guarantee consistency.

And synchronizing data is far more than distributed editing applications and databases. We are in a world where people expect their documents and applications to sync everything, all the time, over unreliable channels.

This is no longer a special feature of specialized applications It’s the new normal.

So back to the Command Pattern. Sure, it’s twenty years old. Sure, undoing user edits is well-understood. But we should never look at a pattern and think that because we understand the example use case for the pattern, we understand everything about the pattern.

For the command pattern, undo is the example, but treating invocations as first-class entities that can be stored, queried, and transformed is the underlying idea. And the opportunity to use that idea has never been greater.

image credits

https://www.flickr.com/photos/fatedenied/7335413942 https://www.flickr.com/photos/fatedenied/7335413942 https://www.flickr.com/photos/mwichary/2406482529 https://www.flickr.com/photos/tompagenet/8580371564 https://www.flickr.com/photos/ooocha/2869485136 https://www.flickr.com/photos/oskay/2550938136 https://www.flickr.com/photos/baccharus/4474584940 https://www.flickr.com/photos/micurs/4906349993 https://www.flickr.com/photos/purdman1/2875431305 https://www.flickr.com/photos/daryl_mitchell/15427050433 https://www.flickr.com/photos/the00rig/3753005997 https://www.flickr.com/photos/robbie1/8656027235 https://www.flickr.com/photos/mwichary/2406489333 https://www.flickr.com/photos/pedrosimoes7/17386505158 https://www.flickr.com/photos/a-barth/2846621384 https://www.flickr.com/photos/mleung311/9468927282 https://www.flickr.com/photos/bludgeoner86/5590795033 https://www.flickr.com/photos/49024304@N00/ https://www.flickr.com/photos/29143375@N05/4575806708 https://www.flickr.com/photos/30239838@N04/4268147953 https://www.flickr.com/photos/benetd/4429314827 https://www.flickr.com/photos/shimgray/2811100997 https://www.flickr.com/photos/wordridden/4308645407 https://www.flickr.com/photos/sidelong/18620995913 https://www.flickr.com/photos/stawarz/3848824508 https://www.flickr.com/photos/mwichary/3338901313

notes

-

This is vaguely related to working with promises in JavaScript, although we won’t explore that as this is decidedly not a talk about JavaScript, it’s a talk in JavaScript. ↩

-

There are other problems, like overlapping commands, but this is enough to move along and illustrate the kind of thinking we need to do with first-class invocations. ↩

-

Another problem is that we have made a massive number of hand waves. We only correctly handle edits that do not overlap. We’ll talk about this a little later. ↩

-

Many programmers will take a strong exception to using

this.has(theirEdit) || this.append(theirEdit)as a control-flow construct. Mind you, most people don’t have to make a method fit on a slide. Be more explicit in real code. ↩ -

Furiously hand-waving over edits that overlap, of course. Not to mention pesky protocol issues like unreliable communication channels. ↩

-

And the “overlapping edits” question applies to undos. Consider what happens if Bob inserts the word

co-operation, and Alice edits it to the more literarycoöperation. Now Bob hits undo, expecting the word he just typed to vanish. What happens? ↩ -

In fact, this presentation was written in Markdown and presented using DeckSet, precisely because this affords using git to manipulate its history. ↩

This content originally appeared on raganwald.com and was authored by Reginald Braithwaite

Reginald Braithwaite | Sciencx (2016-01-19T00:00:00+00:00) First-Class Commands (the annotated presentation). Retrieved from https://www.scien.cx/2016/01/19/first-class-commands-the-annotated-presentation/

Please log in to upload a file.

There are no updates yet.

Click the Upload button above to add an update.