This content originally appeared on Level Up Coding - Medium and was authored by Erik Hermansen

I keep seeing advice articles on how engineers can get promoted. Some of them wallow in office politics and bitter stories of unfairness. Others advocate a set of general engineering virtues that would overwhelm Aristotle. And I often see advice to move up by moving out, aka “job-hopping”.

I don’t want to pick on these writers. But I feel like most of them don’t really understand the companies they’ve worked for. It’s like listening to frogs give lectures on how to escape boiling pots. They understand water, pain, freedom, and a few other relevant concepts. But they don’t quite understand why someone would put them into a pot and place that pot on a stove.

I’ve been promoted when I was an engineer. I have promoted engineers multiple times as a manager. I’ve contributed to the criteria and policies around promotion. I’ve done this at multiple companies. That’s where my confidence comes from on this topic.

Let’s talk about the boring stuff that is a necessary part of talent review in nearly any IT-based company beyond a hundred employees.

The Talent Review Cycle

Did you start to click away when I said the words “talent review cycle”?

That’s the problem! It’s super-boring stuff. But if you really want to move up in your company, you should get these things into your head.

Most companies have between 1 and 4 talent review cycles each year. It’s a period of time over which your talents, aptitudes, and contributions are evaluated. At the end of a cycle, your manager and others will make some type of evaluation about you that goes into HR’s records. And that evaluation will determine eligibility for promotions and raises. There’s more to getting promoted than just that evaluation — we’ll get to the rest.

The exact form of that evaluation will differ from one company to the next. It could be:

- Single-axis rating, e.g. scale of 1 to 5.

- 9-box rating

- Stack ranking

How the evaluation is arrived at differs per company as well. It’s quite common to have the evaluation use multiple sets of inputs. Here are some typical things that go into employee evaluations.

- Employee/manager rating alignment

- Peer review surveys

- Productivity metrics

- Team KPIs (sometimes, how well the overall team is doing affects individual promotions)

- Manager calibration sessions (managers convene to make sure they are being reasonably consistent in employee evaluations)

I got bored typing that. I’m sorry. It’s very boring.

The exact combination of boring things that go into your talent review cycle at your specific company remains for you to learn.

With this article, I am not following the rules for getting people to pay attention to me on the Internet. Because I’d rather just hand you the Useful Truth, instead of screaming compelling, clickbaity things. I warned you with the dull headline. It probably should have been something like, “Your Next Job is Already Dead According to Future Bitcoin Billionaires” or “The Five Things You Must Do Yesterday plus also Elon Musk”.

Working Hard is Not Enough

Let me guess…

There was an all-hands meeting at your company this year. And somebody from HR droned for 36 minutes about upcoming revisions and improvements to their talent review program. It was super-boring, and you tried to pay attention for a while. But eventually, you turned the volume down on the call and concentrated on getting your PR merged in before the end of the sprint.

And you might have justified tuning out because you figured you’d focus on doing the work the company was paying you to do, e.g. write code. And people should see your hard work and reward you accordingly, e.g. by upgrading your title and pay.

I heavily sympathize with this line of reasoning. And I’ve spent time as a manager getting recognition for these work-focused engineers.

But it’s in your best interest to understand how the talent review process works at your company and be engaged in it. And of course, it is actually part of your job to know about wider company stuff not directly related to your day-to-day work.

One-on-Ones with Your Boss

Do you have 1-on-1s with your manager? Weekly? If not, then ask for them.

How are you spending your 1-on-1s? You and your boss might be steering toward “comfort” topics, e.g. your favorite programming language. There’s nothing wrong with that. But remember to place your career development on the agenda for at least some of the meetings. Or if your manager is trying to bring it up, then lean into that topic. Even if it’s awkward for you.

There are going to be questions like:

- How does the talent review cycle work?

- What is the career path that you are interested in? E.g. Are you keen on being an architect in the company? Do you want to get into management?

- What is the next promotion or role change you should target?

- What are the things you should do to get there?

Think about that last question.

The answer to it will be wildly different from situation to situation. This is why I have a problem with the general advice thrown around in other “How To Get Promoted” articles.

You will need to talk to your manager — not the Internet — to understand the path to promotion specifically for the time and place you occupy in the Universe. No author of a Medium article, including me, will be able to illuminate this path in sufficient detail. Listening to general advice on your specific situation is like Lee Harvey Oswald listening to InfoWars to figure out who shot JFK.

Here are some real-world examples from my own experience of answers given by managers (including myself) to the “How do I get promoted?” question:

Manager: “Because you changed from a team lead to individual contributor role last year, I need to assign you to some projects that demonstrate your engineering skills.”

Manager: “I can’t put a strong promotion packet together for you in this talent review cycle, so let’s target the next one.”

Manager: “Are you sure you want to go to a staff engineer role? You’ll be spending less time coding and more time in meetings and writing docs. We could also aim to keep you at your current title with a higher pay band.”

Manager: “I can see putting you forward for a promotion next year. But to be honest, there are some areas where you’re not meeting expectations for your current level, like managing your time with multiple projects. So we work together on your promotion path. But let’s set expectations that it will take time and real effort.”

…and these are snippets from much longer conversations. These specific details in the examples probably aren’t relevant to you . My overall point was to show the level of individual tailoring you can expect. When you’re on a promotion track, you’ll be covering topics like this at least once a month.

Do you feel some apprehension over speaking about your career progression? Most people would. Here are some reasons that could explain that fear:

- It feels like you’re forcing your manager to talk about it.

- You don’t want to be seen as entitled or overly ambitious.

- You’re worried about your manager’s evaluation of you being low.

- You feel ignorant of your own value relative to others on the team. Is it even appropriate to try for a promotion?

- You could create extra work for yourself in the form of goal-setting.

- You’re worried that you’ll be required to fake enthusiasm and company loyalty that don’t fit your personality.

- You don’t want a social penalty to land on you for attempting a promotion before others think you are ready.

Any of these reasons could have some slight validity for concern. But don’t let them weigh larger in your mind than they should. Just remember that it is never wrong to discuss your career path with your manager. And it’s expected that you would discuss your career path, and essentially inevitable unless your manager is avoiding that discussion for some reason.

You can also gather information by casually asking the “how do I get promoted?” question without committing yourself to any goals or actions. For this, you just ask some unassuming questions, listen, stay positive, and stop yourself from making any promises. “Let me think about this further,” is a perfectly fine way to end just about any conversation.

Reluctance from the Other Side

Here are some real reasons why managers might avoid talking about your career path or constrain the conversation. And some of them are admittedly troubling:

- Your manager is short on time.

- Your manager is short on the emotional energy needed to engage in a conversation about your future. (Seriously, it can be very draining!)

- Your manager doesn’t yet understand the talent review process and wants to be better prepared.

- Either you or your manager are new to your team, and your manager hasn’t had enough time to see how you work and what you can do.

- The distribution curve or similar constraints limit how many promotion candidates can be put forward in a talent review cycle, and you are essentially waiting in line behind someone else’s promotion attempt.

- Your manager needs some less-ambitious people on their team with low to average ratings to fit the distribution curve, and was hoping you would be one of them. (Ouch!)

- Your manager sees you as under-performing, and for tactical or emotional reasons, is avoiding a confrontation.

Again, what I said in the previous section applies — it is always appropriate to discuss career path with your manager. If your manager has a good reason for delaying that conversation, they can just tell you. If there is some bad news for you to learn in the conversation, you’ll be better off hearing it and knowing where you stand.

I want to say more about how distribution curves work in compensation. Most employees don’t understand them and the ramifications are intense. But that is a nuanced discussion for another article.

It’s Not Up to your Boss

When I was a new engineer, I used to think promotion decisions were as simple as my manager just telling HR that I’d earned my wings. And maybe in some of the smaller companies I worked for, that was true.

But now I know better. And you should too.

Unless, you’re working at a start-up, the process will probably follow this pattern:

- You ask your boss for guidance on how to get promoted. They will set some goals and tasks for you.

- You do the work, and your boss is happy with you.

- At the end of a talent review cycle, your boss submits a proposal to promote you to an independent panel within the company.

- That panel reviews the proposal and decides “yes” or “no” on your promotion.

You need your manager’s enthusiastic support to get your promotion. But they don’t make the final decision.

The submitted proposal will probably be at a similar level of documentation as an Ivy League university application. Or a home inspection report. I’m not joking. It could be 3–10 pages, with links to supporting content, collected testimonials, and metrics-based arguments.

Then there are calibration sessions managers attend to argue amongst themselves why their reports deserve different ratings. And these are often coupled to fitting distribution curves, e.g. 20% of the employees within a group need to have low ratings. These can be painful experiences for the managers as they work to be fair to their reports and also satisfy the overall requirements that the company sets forth.

To put you forward for promotion successfully within a talent review process can easily take 20–40 hours of work from your manager throughout the cycle — just for you. The review panel may reject the proposal, hopefully with some useful feedback. And then you and your manager start the process again for another attempt in the next talent review cycle. At one company, I saw the same candidate put forward for promotion three times before being accepted. After each rejection, the candidate’s manager dutifully reassembled a thick dossier for the next cycle to try again.

Think of your boss, not as the decider, but more like an attorney arguing a case on your behalf.

Talent Review — Not Actually Boring

There’s a set of vocabulary and concepts that goes along with any discipline that is essentially the tools of your trade. And we’re prone to putting more value on understanding the tools we use in our work than those of other trades.

Suppose, as an engineer on a project, you tell a product owner, “I need to spend a week refactoring this module to improve the code base’s maintainability.” They might just hear, “BLAH BLAH BLAH… I am one week late and here’s some irrelevant excuse I came up with.”

And likewise, someone from a different discipline like Human Resources could say to you, “We’ve moved the responsibility for calibrating ratings against the distribution curve to the division level so we can have a larger pool of people’s ratings to fit against.” And you might just hear, “BLAH BLAH BLAH… we’re making some arbitrary changes that sound impressive but probably don’t matter.”

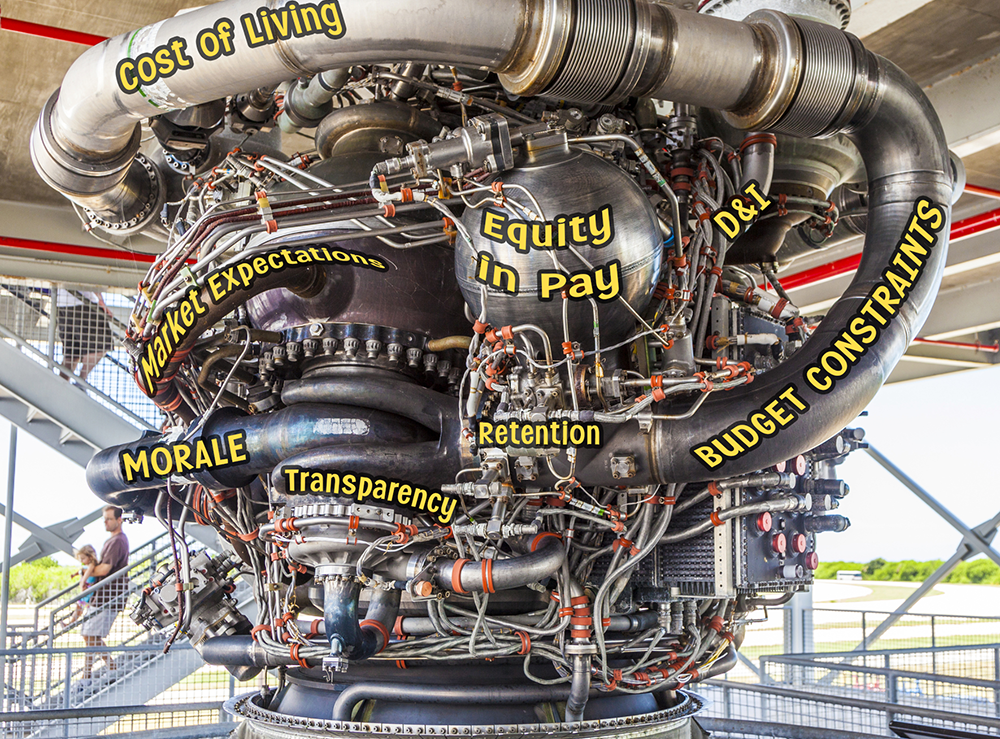

But figuring out talent review and compensation inside of a company is fiendishly complex. HR has to design a socio-technical system that solves for a set of goals with inherent tradeoffs. How to avoid gross pay inequity between people making similar contributions while still enticing top performers to stick around? How to keep morale high after delivering performance ratings when more than half of the employees think they are doing better than average? (Statistically, it can’t be true, yet most people see themselves in the top half.)

Maybe the language used to describe talent review is a kind of blanket thrown over a roiling moral chaos to hide it. If you think deeply enough about compensation, you will find your thoughts overlapping with people like Karl Marx and Milton Friedman. It could be a blessing that we’re collectively a bit bored with the rules and processes that decide how we’ll be paid. Think of the epic arguments we’d get into!

There’s a famous line from David Mamet’s Glengarry Glenn Ross, where a manager defines a compensation system to a room of salespeople in simple and compelling terms:

“As you all know first prize is a Cadillac El Dorado. Anyone wanna see second prize? Second prize is a set of steak knives. Third prize is you’re fired.”

The fierce simplicity of this statement has strength to motivate — “fight or die” basically. But I think most of us prefer to work within a more nuanced system that attempts to balance all the different goals of a company and its employees. And such a system, adequately designed, will fail to be describable in simple and compelling terms.

The Checklist

I write such long articles. I wouldn’t blame you for skimming down to the bottom. That’s why I put a quick checklist here for you:

- Understand your company’s talent review cycle, what you’re expected to contribute (e.g. self-assessments), and how your actions within the cycle affect your chances of promotion.

- Establish weekly 1-on-1s with your manager, if you don’t already have them.

- Talk with your manager about your career path, and set explicit goals and tasks to support your promotion.

- Actually do the things from step 3 to convince your manager that you are ready for promotion.

- Your manager will decide to put you in for promotion. And with some luck, you’ll get it.

Good luck in your pursuits!

Level Up Coding

Thanks for being a part of our community! More content in the Level Up Coding publication.

Follow: Twitter, LinkedIn, Newsletter

Level Up is transforming tech recruiting ➡️ Join our talent collective

Getting Promoted: The Boring Work You’ll Need to Do was originally published in Level Up Coding on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

This content originally appeared on Level Up Coding - Medium and was authored by Erik Hermansen

Erik Hermansen | Sciencx (2022-07-11T00:14:57+00:00) Getting Promoted: The Boring Work You’ll Need to Do. Retrieved from https://www.scien.cx/2022/07/11/getting-promoted-the-boring-work-youll-need-to-do/

Please log in to upload a file.

There are no updates yet.

Click the Upload button above to add an update.