This content originally appeared on Open Culture and was authored by Ayun Halliday

The Austrian symbolist painter, Gustav Klimt, a driving force of the Vienna Secession, has joined the ranks of famous, dead artists being served up as pricey, super-sized, Instagram-friendly immersive experiences.

Jane Kallir, author of Gustav Klimt: 25 Masterworks and co-founder of the Kallir Research Institute, a foundation dedicated to furthering the study of Austrian and German Modernists, is not buying into this approach.

Having visited the Gold in Motion immersive Klimt exhibit at New York City’s recently inaugurated Hall des Lumières with Artnet’s Ben Davis, she definitely has some notes:

They take liberties with the originals. If you know the originals well, which I do, it’s sometimes hard to figure out what they were working from. The color is sometimes way off. And some of the images are not by Klimt at all. They seem like pastiches of Klimt or pieces of Klimts that they’ve pasted together in different ways…these images are blown up to a height of, what, 20 feet? It really doesn’t work, aesthetically. Klimt’s drawings are especially difficult because they’re so delicate, at times almost invisible.

But mustn’t some young visitors, after posting the plethora of selfies that motivate many a pilgrimage to this “multi-sensory celebration,” be moved to learn more about the artist it’s cashing in on?

That’d be a good thing, right?

Of course it would, and Paul Priestley provides a great introduction to Klimt’s life and work in the above episode of his Art History School web series.

We grant that spending 13 minutes with a middle-aged arts educator in a festive vest is a less sexy-seeing prospect than “step(ping) into a wonderland of moving paintings” to be “amazed by the golden era of modernism.”

But Priestley offers something you can’t really focus on while gawking at enormous 360º projections of The Kiss during a $35 timed entry – historical context and a generous portion of art world dish on a “lifelong bachelor who had countless liaisons during his lifetime, usually with his models, and is rumored to have fathered more than a dozen children.”

Priestley makes clear how the young Klimt’s career took a fateful turn with Philosophy (below), part of a massive commission for the ceiling of Vienna University’s Great Hall, that was ultimately destroyed by the Nazis, but has since been resurrected after a fashion using AI, black and white photos, and eyewitness descriptions.

When Klimt’s first go at it was displayed, it was savaged by critics as “chaotic, nonsensical and out of keeping with the intended setting.”

Philosophy’s drubbing put an end to Klimt’s official commissions, but private ones flourished due to the bohemian painter’s “beautiful women in elegantly languid and flattering poses.”

Imagine how those status conscious society matrons would have reacted to seeing their likenesses tapped as immersive art, which Vice’s Alex Fleming-Brown pegs as “the latest lazy lovechild of TikTok and enterprising warehouse landlords.”

Surely they would have relished the attention!

Well, everyone, that is, except Margaret Stonborough-Wittgenstein, sister of Ludwig, who chafed at her appearance in Klimt’s 1905 bridal portrait as “too innocent, timid and girlish…” and stuck the picture in the attic.

C’mon, they can’t all be The Kiss.

It’s an astonishing painting, but there’s so much more to discover about Klimt and his four decades worth of work.

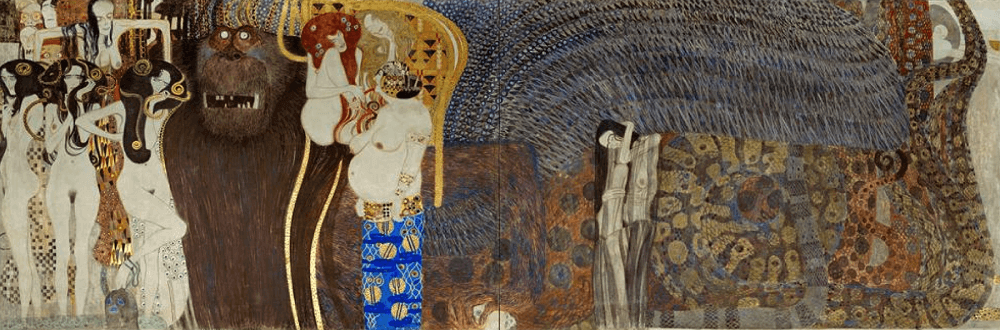

But first, with apologies to any readers who genuinely enjoy immersive art exhibits – many do – here are Jane Kallir’s not entirely conciliatory thoughts on Beethoven Frieze, Klimt’s voluptuous vision of lust, love and disease, which was deliberately enhanced by accompanying sculpture and live music when it made its public debut in 1902, and is currently being parceled out and writ large in digital form in the building formerly known as New York’s Emigrant Industrial Savings Bank:

I asked myself whether Klimt would have approved of the Beethoven Frieze projections. I believe most artists embrace cutting-edge technology, whatever it may be in their day and age. The Beethoven Frieze segment is a Gesamtkunstwerk on a scale that Klimt might have dreamed of—might have. This is the one part of the presentation that could be faithful to his intentions.

Related Content

Gustav Klimt’s Masterpieces Destroyed During World War II Get Recreated with Artificial Intelligence

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

This content originally appeared on Open Culture and was authored by Ayun Halliday

Ayun Halliday | Sciencx (2023-02-17T09:00:35+00:00) The Life & Art of Gustav Klimt: A Short Art History Lesson on the Austrian Symbolist Painter and His Work. Retrieved from https://www.scien.cx/2023/02/17/the-life-art-of-gustav-klimt-a-short-art-history-lesson-on-the-austrian-symbolist-painter-and-his-work/

Please log in to upload a file.

There are no updates yet.

Click the Upload button above to add an update.